Mapping and Data Visualization with Python (Full Course)

A comprehensive guide for creating static and dynamic visualizations with spatial data.

Ujaval Gandhi

- Introduction

- Get the Course Videos

- Notebooks and Datasets

- Hello Colab

- Matplotlib Basics

- Creating Charts

- Creating Maps

- Using Basemaps

- XArray Basics

- Mapping Gridded Datasets

- Visualizing Rasters

- Assignment

- Interactive Maps with Folium

- Multi-layer Interactive Maps

- Leafmap Basics

- Streamlit Basics

- Building Mapping Apps with Leafmap and Streamlit

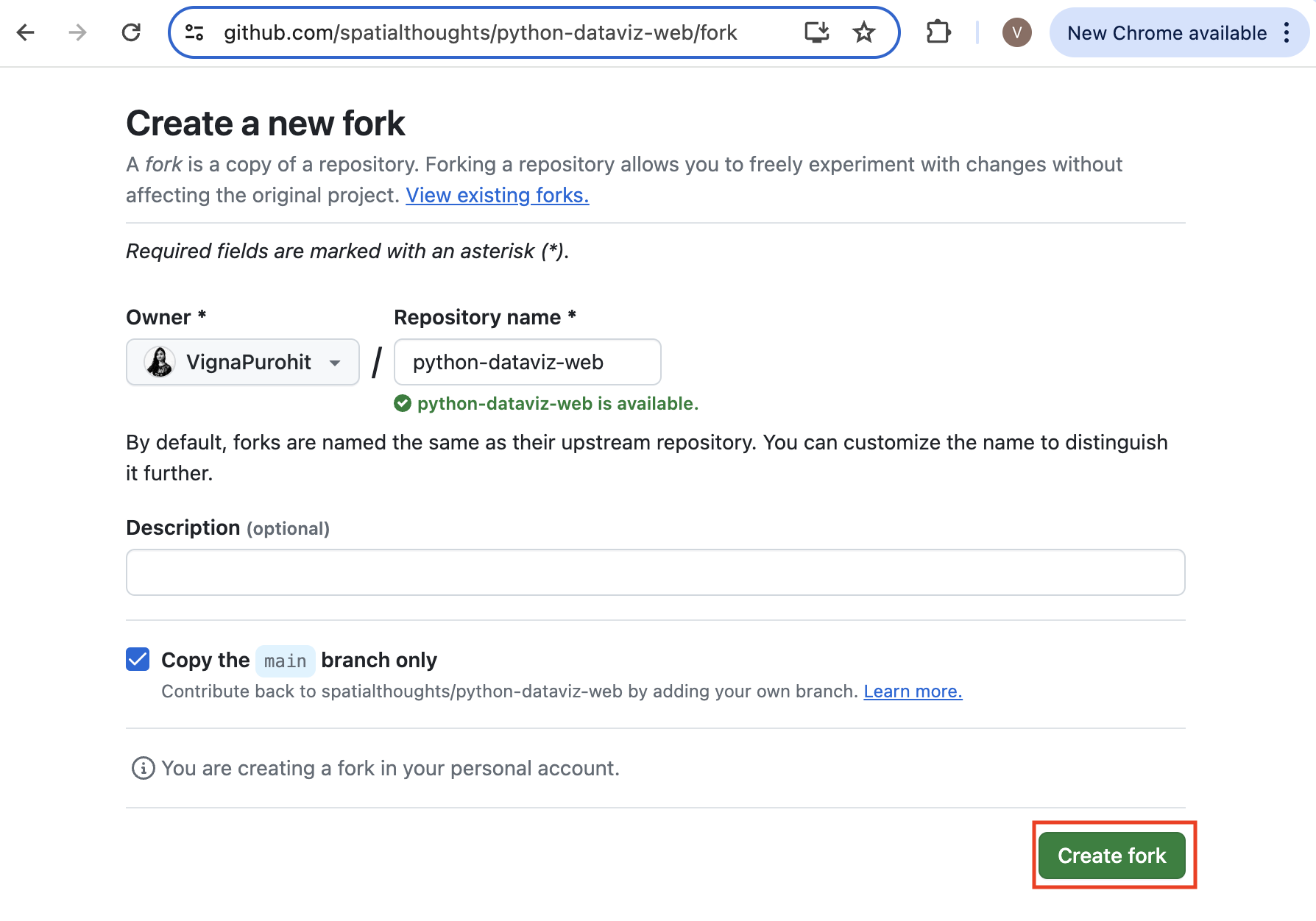

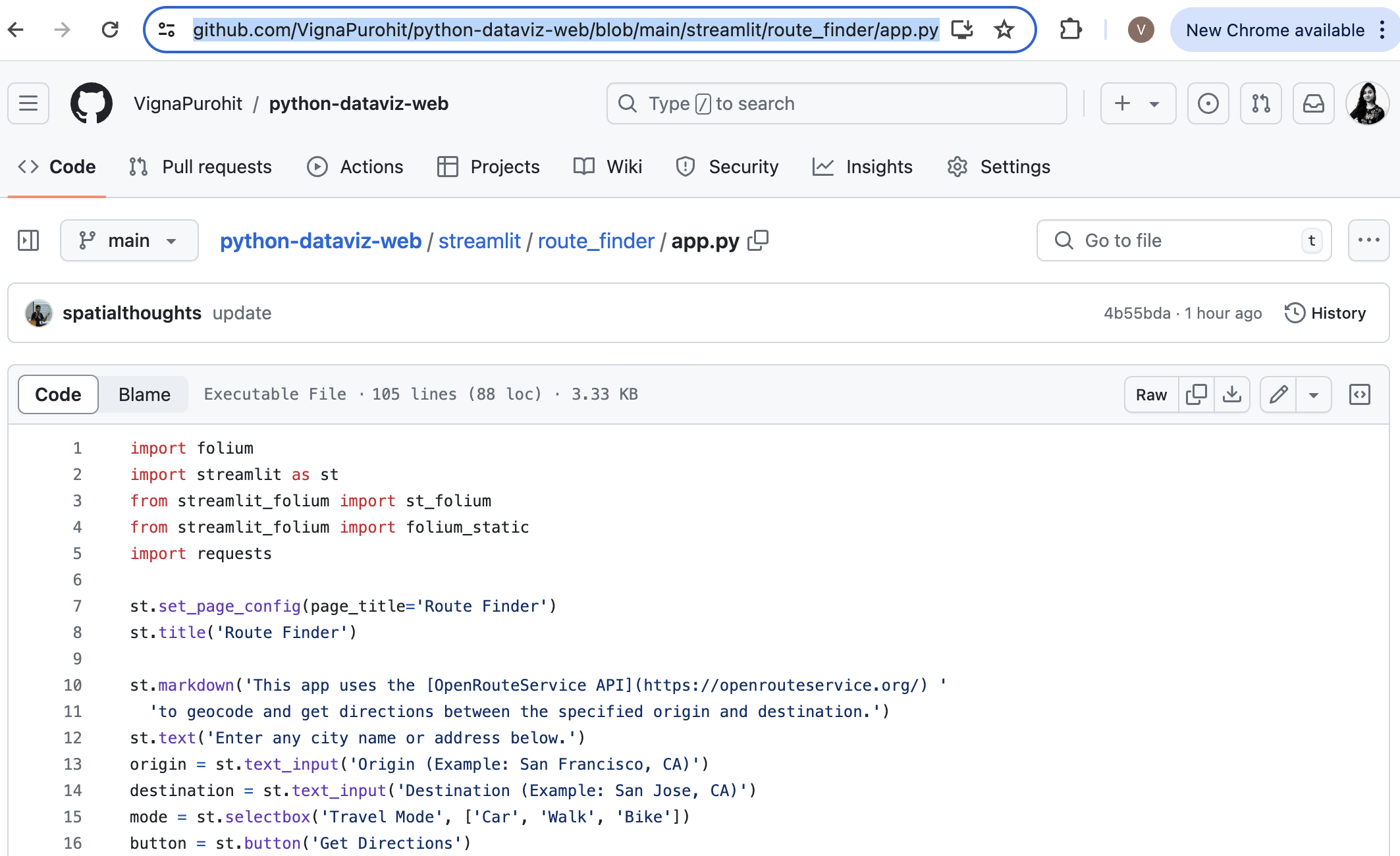

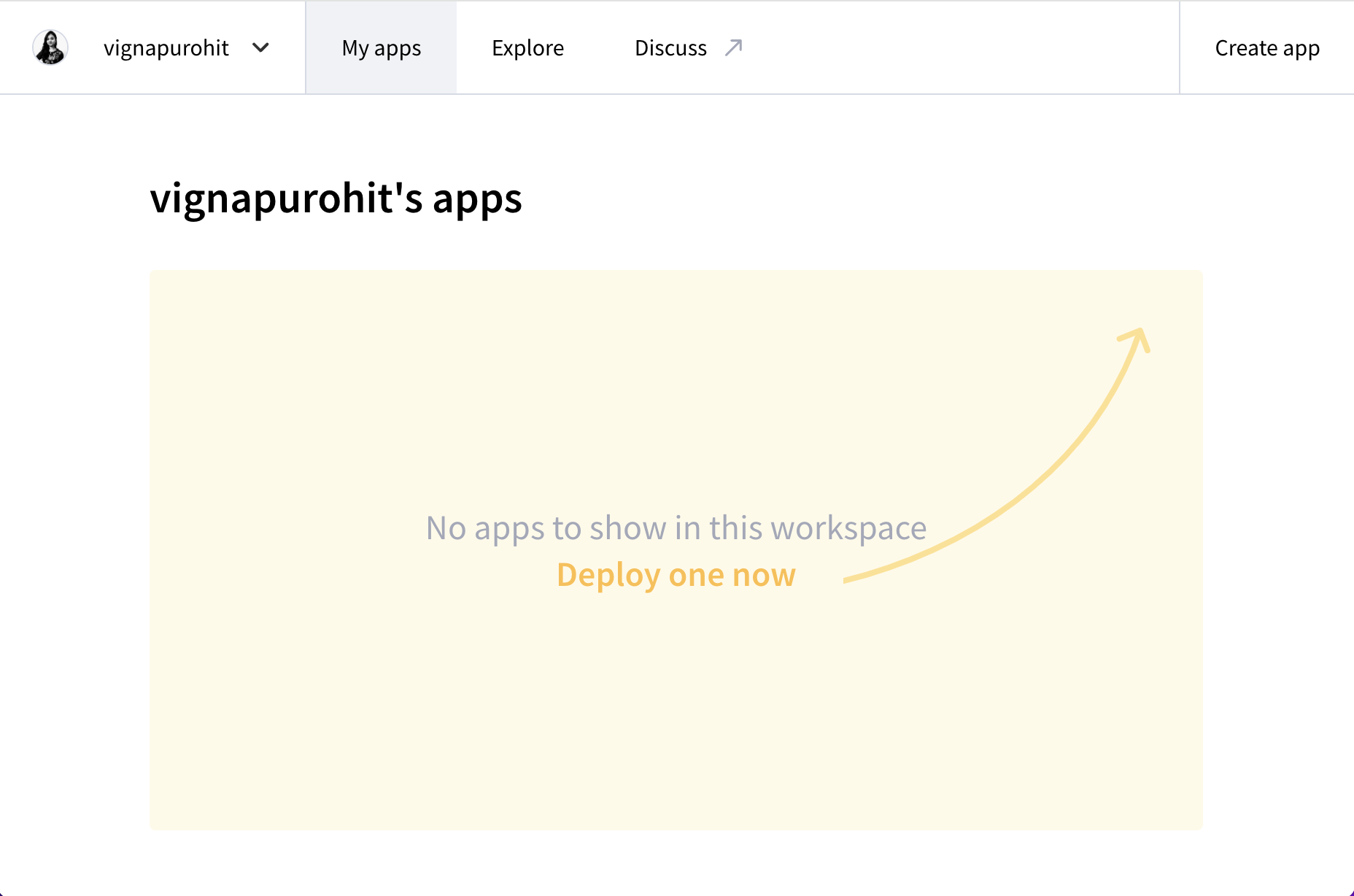

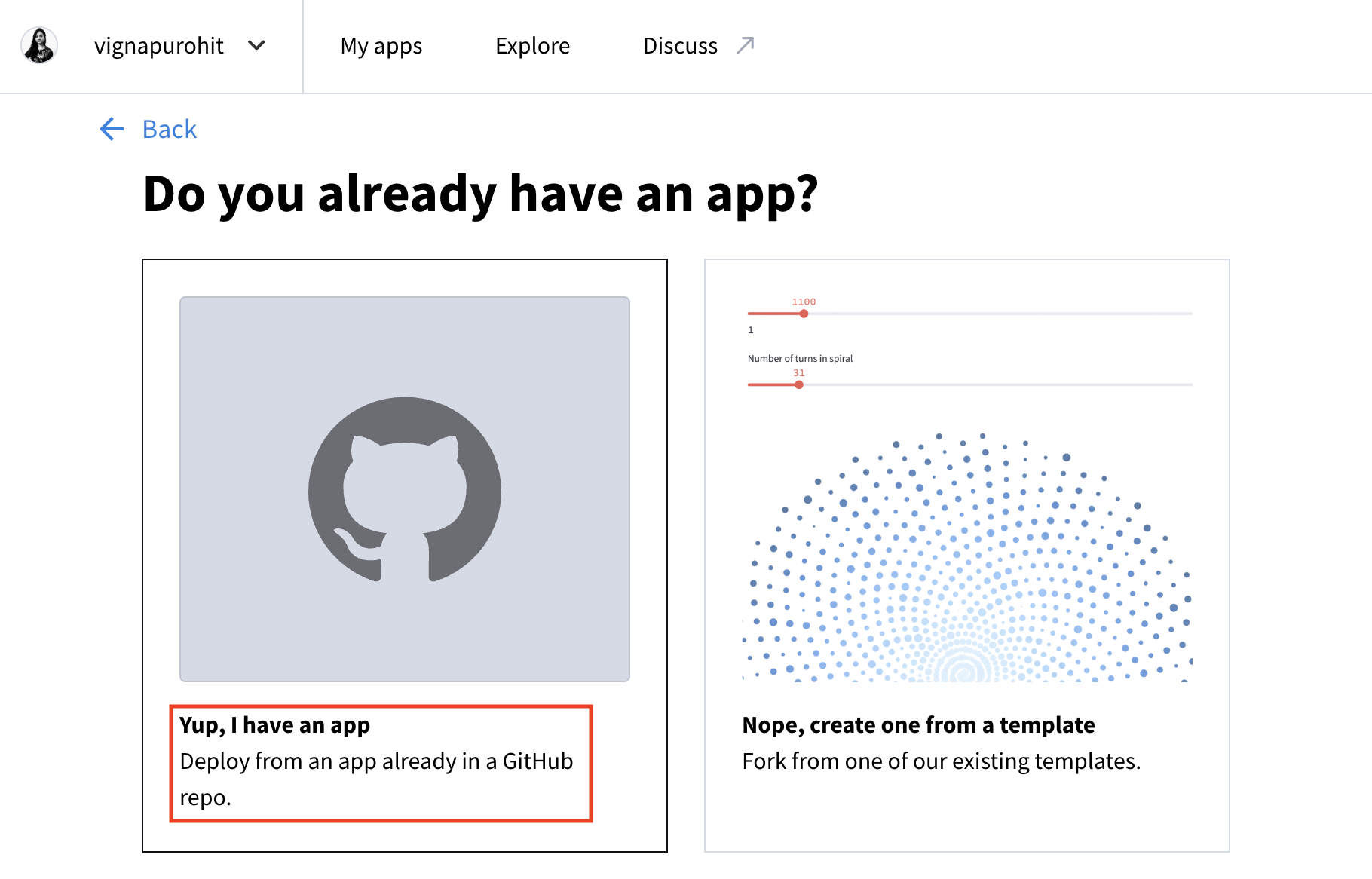

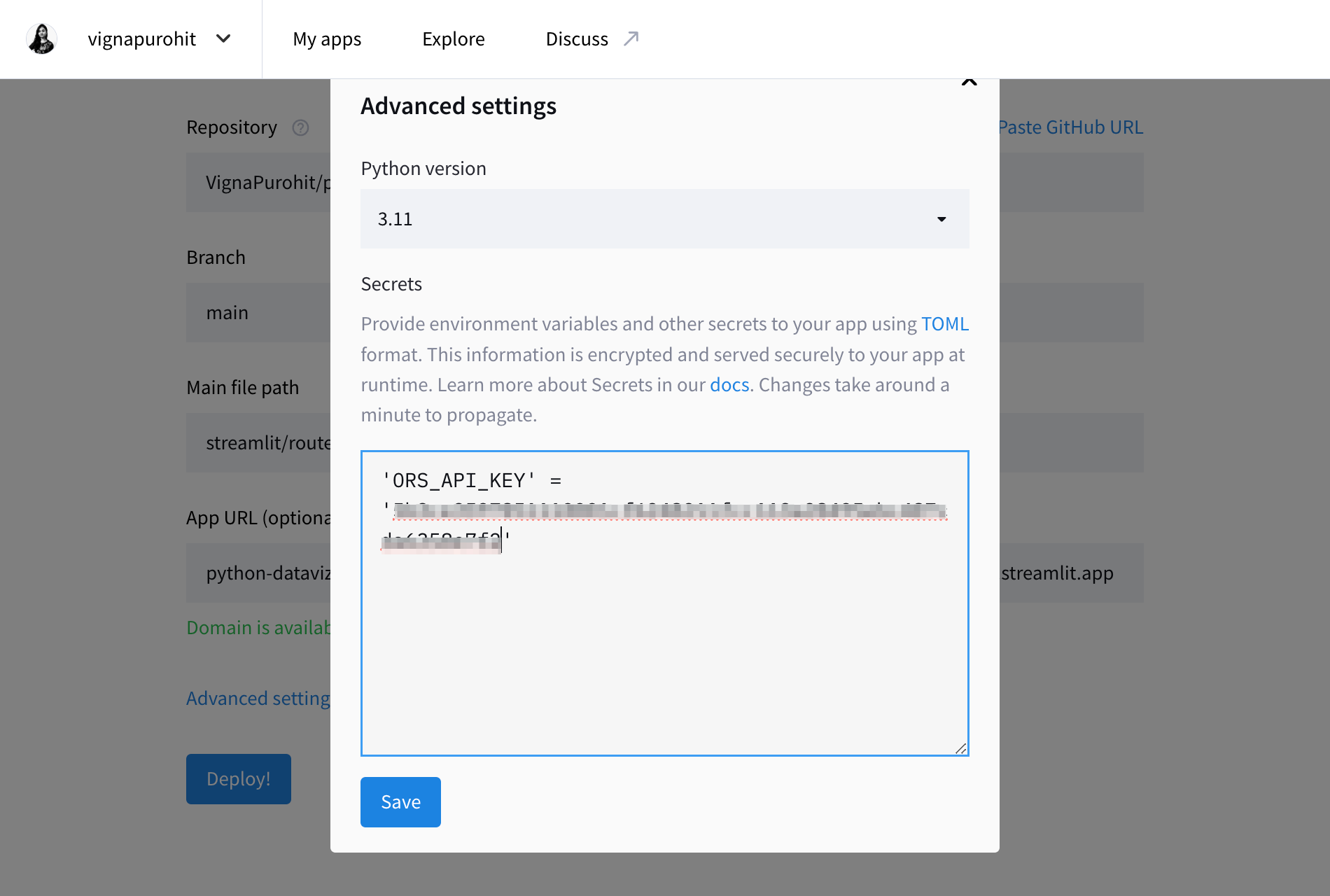

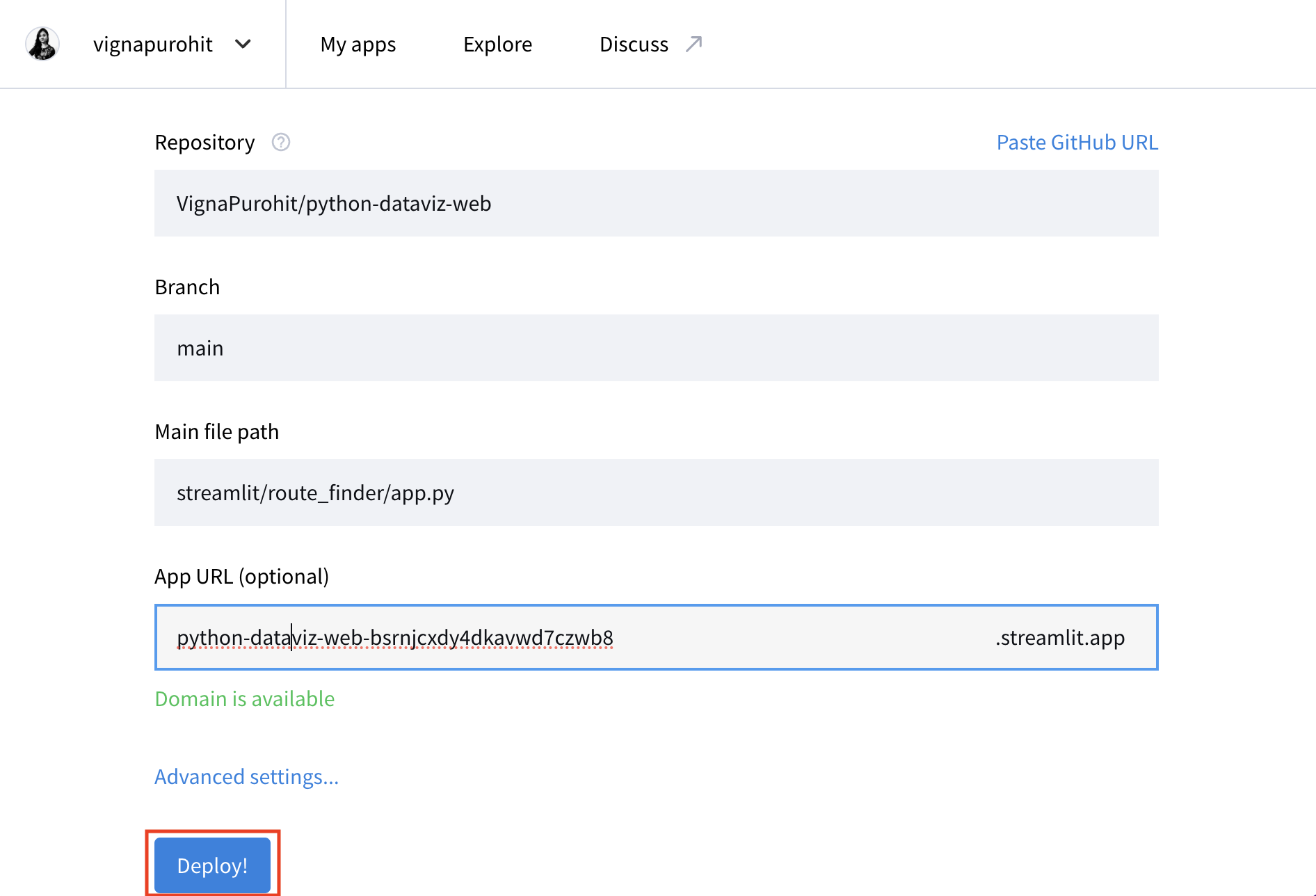

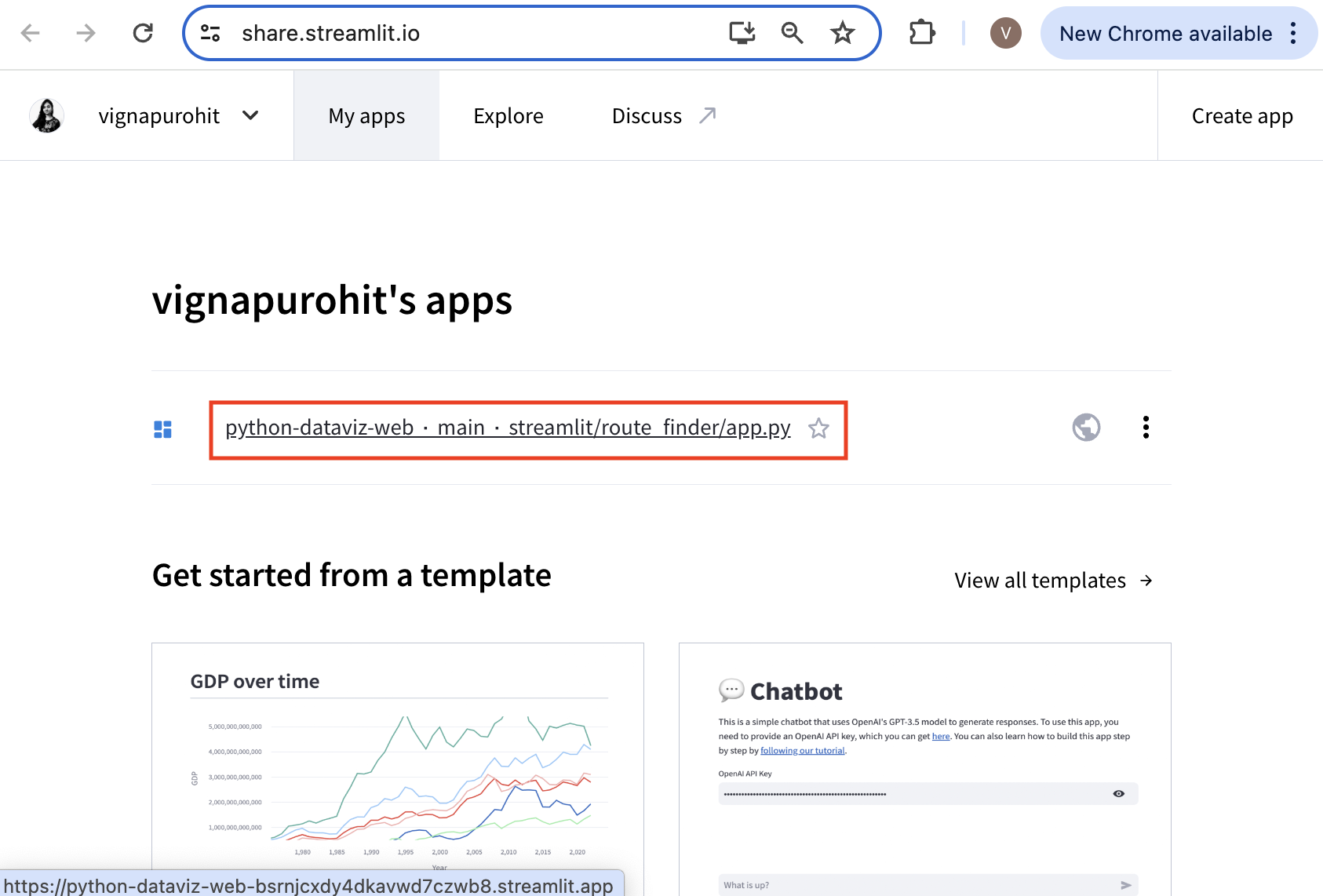

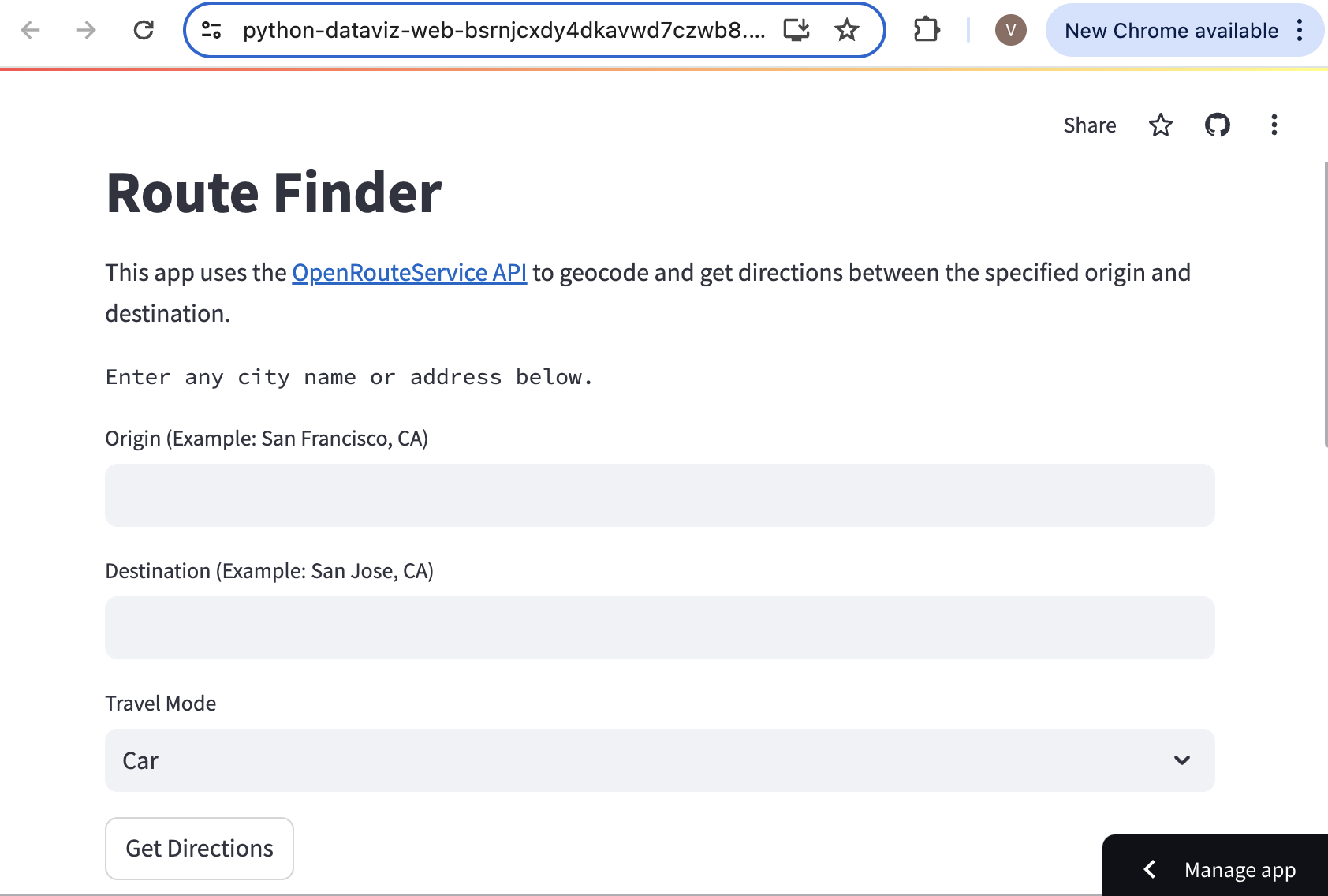

- Publishing Apps with Streamlit Cloud

- Supplement

- Folium

- Contextily

- Advanced

Plotting

- Using Matplotlib Themes and Custom Fonts

- Creating A Stacked Bar Chart

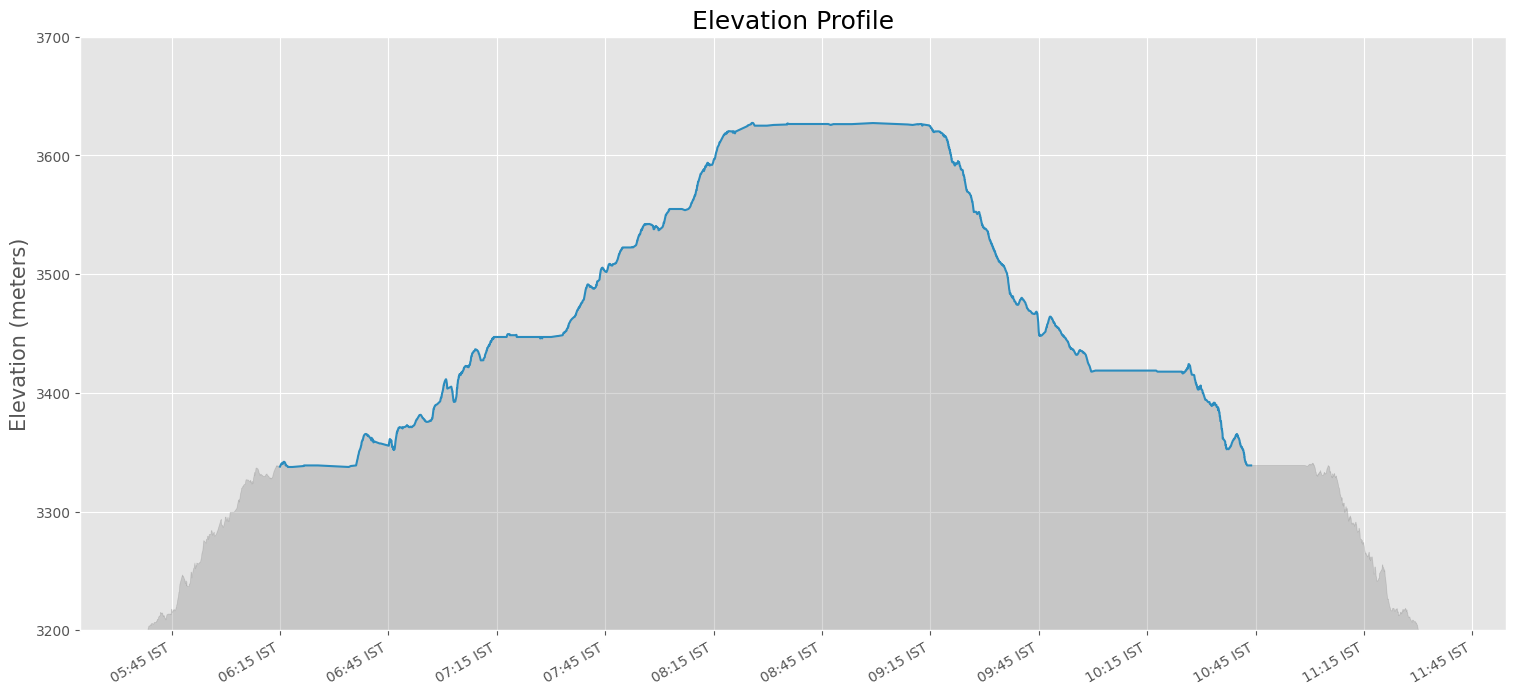

- Elevation Profile Plot from a GPS Track

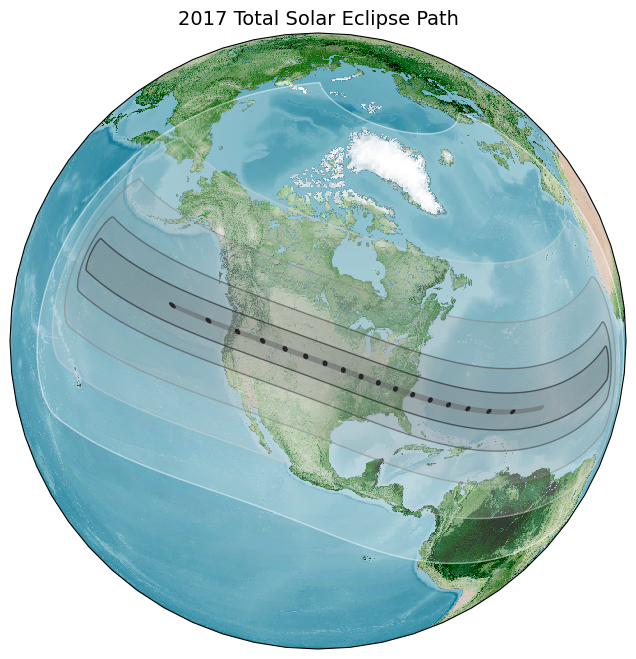

- Creating a Globe Visualization

- Visualizing Monthly Composites

- Creating Maps with Cartographic Elements

- Labeling Features

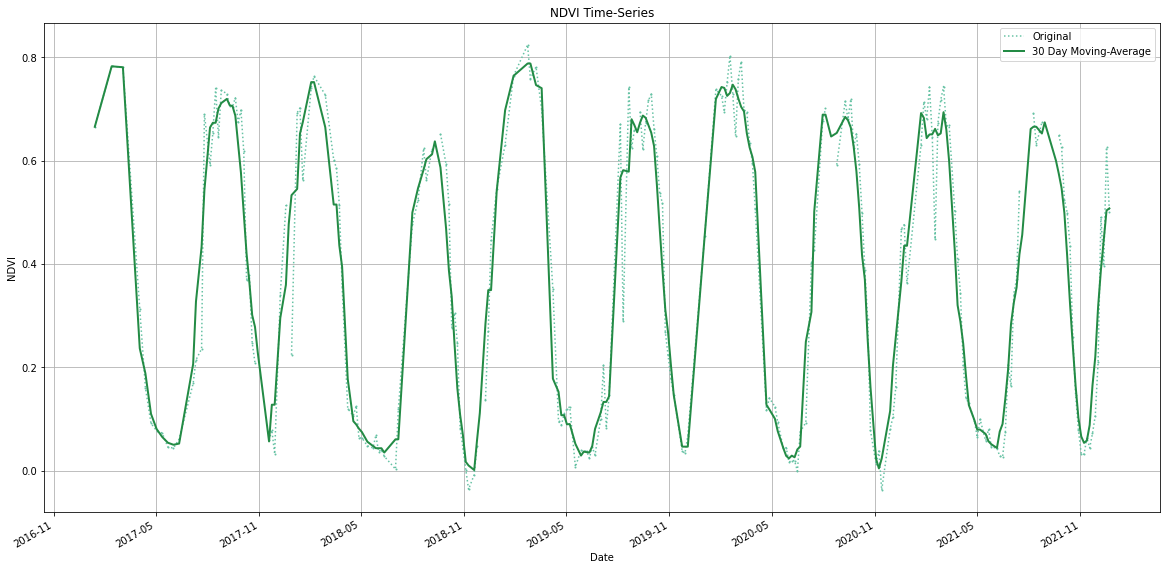

- Creating Time-Series Charts

- Feature Correlation Matrix

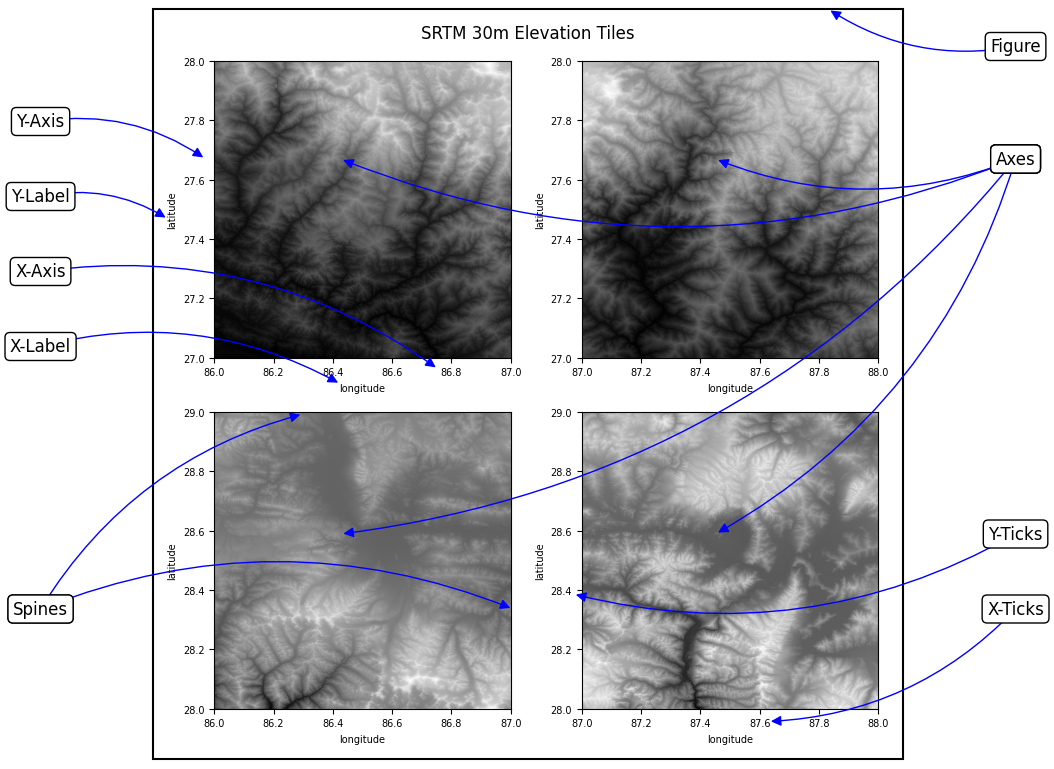

- Matplotlib Anatomy

- Animation

- Leafmap

- Streamlit

- Resources

- Data Credits

- License

Introduction

This is an intermediate-level course that teaches you how to use Python for creating charts, plots, animations, and maps.

Get the Course Videos

The course is accompanied by a set of videos covering the all the modules. These videos are recorded from our live instructor-led classes and are edited to make them easier to consume for self-study. We have 2 versions of the videos:

YouTube

We have created a YouTube Playlist with separate videos for each notebook and exercise to enable effective online-learning. Access the YouTube Playlist ↗

Vimeo

We are also making combined full-length video for each module available on Vimeo. These videos can be downloaded for offline learning. Access the Vimeo Playlist ↗

Notebooks and Datasets

This course uses Google Colab for all exercises. You do not need to install any packages or download any datasets.

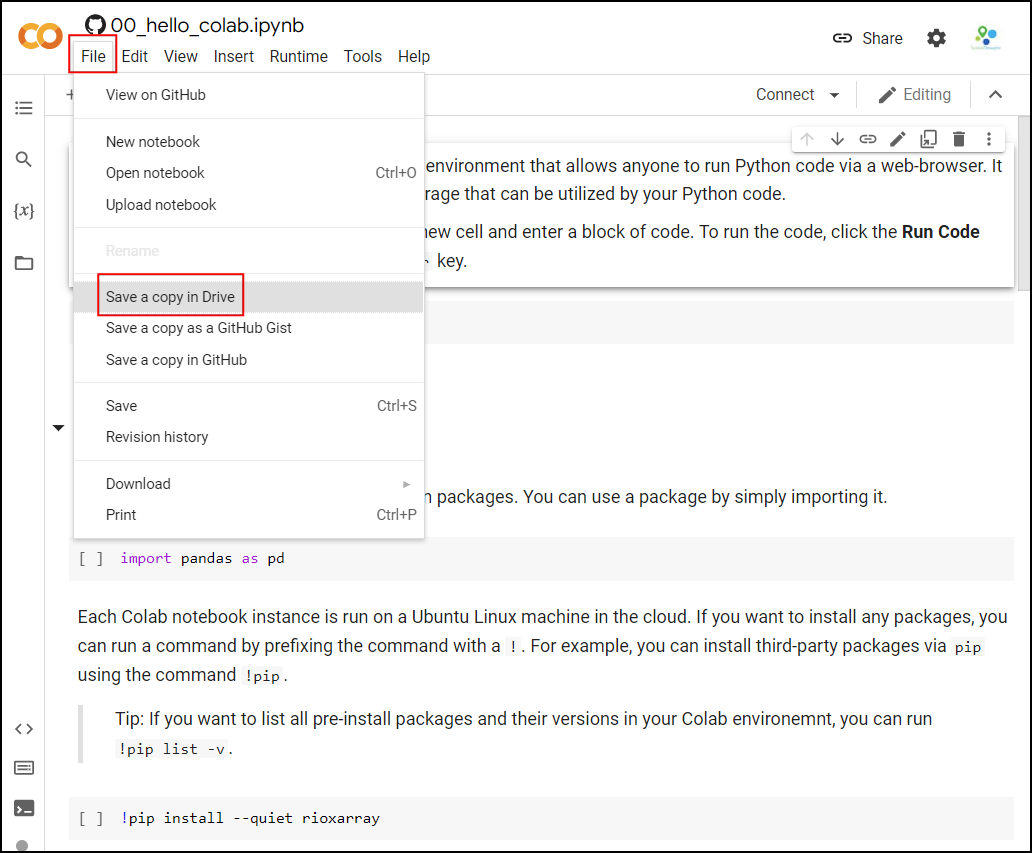

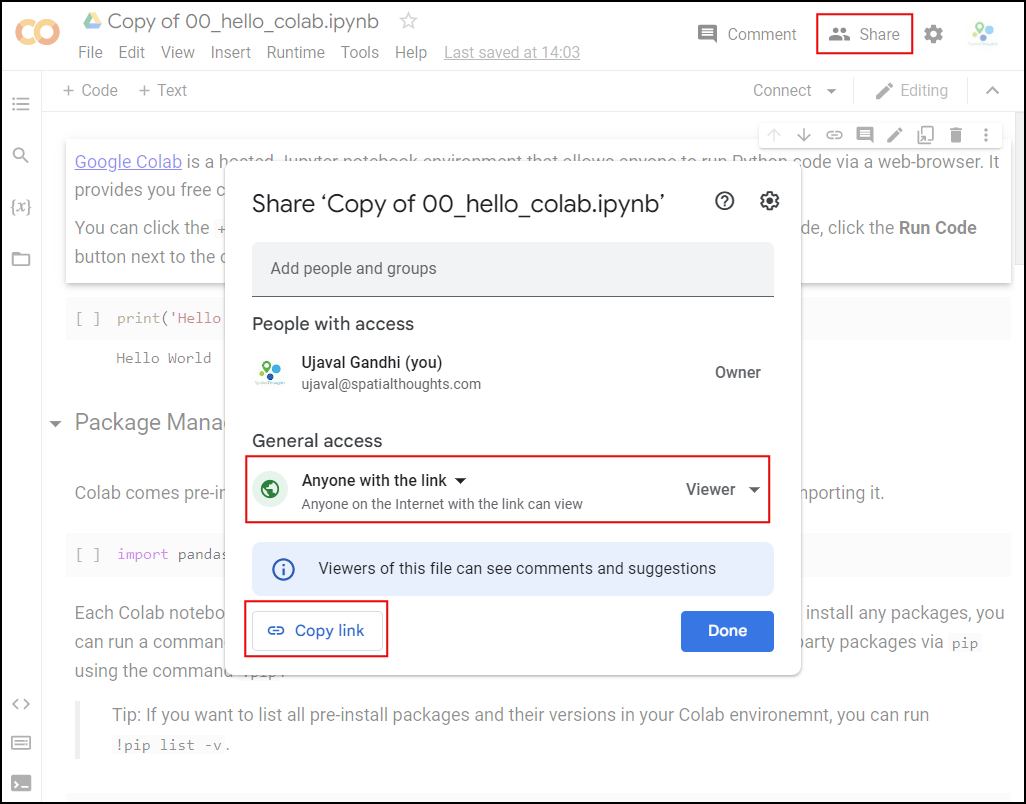

The notebooks can be accessed by clicking on the buttons at the beginning of each section. Once

you have opened the notebook in Colab, you can copy it to your own

account by going to File → Save a Copy in Drive.

Once the notebooks are saved to your drive, you will be able to modify the code and save the updated copy. You can also click the Share button and share a link to the notebook with others.

Hello Colab

Google Colab is a hosted Jupyter notebook environment that allows anyone to run Python code via a web-browser. It provides you free computation and data storage that can be utilized by your Python code.

You can click the +Code button to create a new cell and

enter a block of code. To run the code, click the Run

Code button next to the cell, or press Shirt+Enter

key.

Package Management

Colab comes pre-installed with many Python packages. You can use a package by simply importing it.

Each Colab notebook instance is run on a Ubuntu Linux machine in the

cloud. If you want to install any packages, you can run a command by

prefixing the command with a !. For example, you can

install third-party packages via pip using the command

!pip.

Tip: If you want to list all pre-install packages and their versions in your Colab environemnt, you can run

!pip list -v.

Data Management

Colab provides 100GB of disk space along with your notebook. This can be used to store your data, intermediate outputs and results.

The code below will create 2 folders named ‘data’ and ‘output’ in your local filesystem.

import os

data_folder = 'data'

output_folder = 'output'

if not os.path.exists(data_folder):

os.mkdir(data_folder)

if not os.path.exists(output_folder):

os.mkdir(output_folder)We can download some data from the internet and store it in the Colab environment. Below is a helper function to download a file from a URL.

import requests

def download(url):

filename = os.path.join(data_folder, os.path.basename(url))

if not os.path.exists(filename):

with requests.get(url, stream=True, allow_redirects=True) as r:

with open(filename, 'wb') as f:

for chunk in r.iter_content(chunk_size=8192):

f.write(chunk)

print('Downloaded', filename)Let’s download the Populated Places dataset from Natural Earth.

The file is now in our local filesystem. We can construct the path to

the data folder and read it using geopandas

file = 'ne_10m_populated_places_simple.zip'

filepath = os.path.join(data_folder, file)

places = gpd.read_file(filepath)Let’s do some data processing and write the results to a new file. The code below will filter all places which are also country capitals.

We can write the results to the disk as a GeoPackage file.

output_file = 'capitals.gpkg'

output_path = os.path.join(output_folder, output_file)

capitals.to_file(driver='GPKG', filename=output_path)You can open the Files tab from the left-hand panel

in Colab and browse to the output folder. Locate the

capitals.gpkg file and click the ⋮ button

and select Download to download the file locally.

Matplotlib Basics

This notebook introduces the Matplotlib library. This is one of the core Python packages for data visualization and is used by many spatial and non-spatial packages to create charts and maps.

Setup

Most of the Matplotlib functionality is available in the

pyplot submodule, and by convention is imported as

plt

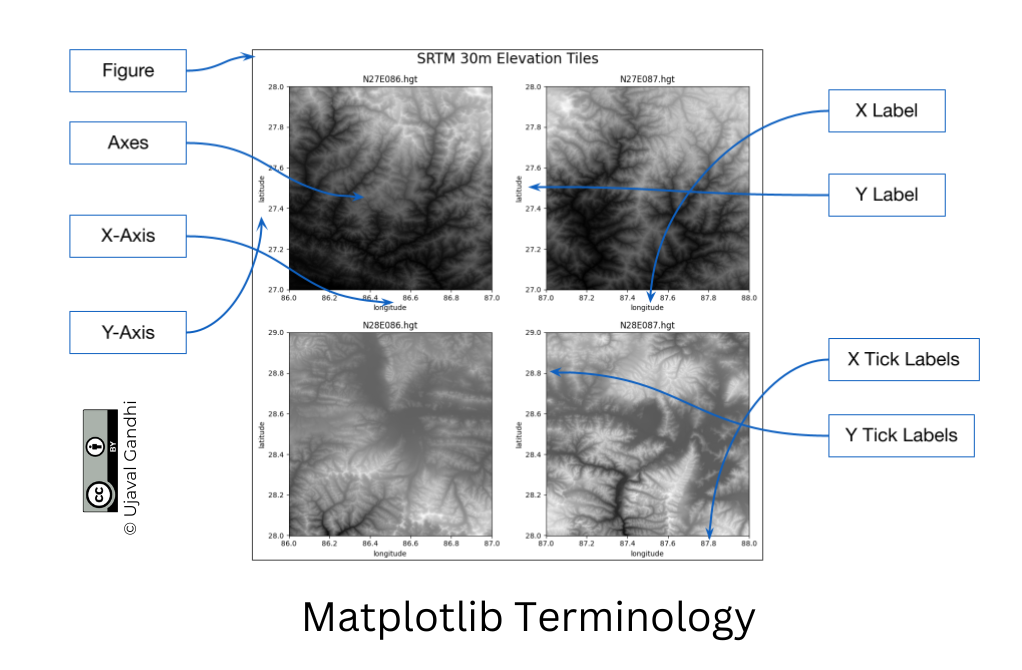

Concepts

It is important to understand the 2 matplotlib objects

- Figure: This is the main container of the plot. A figure can contain multiple plots inside it

- Axes: Axes refers to an individual plot or graph. A figure contains 1 or more axes.

We create a figure and a single subplot. Specifying 1 row and 1

column for the subplots() function create a figure and an

axes within it. Even if we have a single plot in the figure, it is

useful to use this logic of intialization so it is consistent across

different scripts.

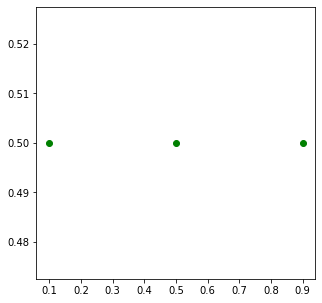

First, let’s learn how to plot a single point using matplotlib. Let’s say we want to display a point at the coordinate (0.5, 0.5).

We display the point using the plot() function. The

plot() function expects at least 2 arguments, first one

being one or more x coordinates and the second one being one or more y

coordinates. Remember that once a plot is displayed using

plt.show(), it displays the plot and empties the figure. So

you’ll have to create it again.

Reference: matplotlib.pyplot.plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(5,5)

ax.plot(point[0], point[1], color='green', marker='o')

plt.show()Note: Understanding *args and **kwargs

Python functions accept 2 types of arguments. - Non Keyword

Arguments: These are referred as *args. When the

number of arguments that a function takes is not fixed, it is specified

as *args. In the function plot() above, you

can specify 1 argument, 2 arguments or even 6 arguments and the function

will respond accordingly. - Keyword Arguments: These are

referred as **kwargs. These are specified as

key=value pairs and usually used to specify optional

parameters. These should always be specified after the non-keyword

arguments. The color='green' in the plot()

function is a keyword argument.

One problematic area for plotting geospatial data using matplotlib is that geospatial data is typically represented as a list of x and y coordinates. Let’s say we want to plot the following 3 points defined as a list of (x,y) tuples.

But to plot it, matplotlib require 2 separate lists or x

and y coordinates. Here we can use the zip() function to

create list of x and y coordinates.

Now these can be plotted using the plot() method. We

specify keyword arguments color and

marker.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(5,5)

ax.plot(x, y, color='green', marker='o')

plt.show()fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(5,5)

ax.plot(x, y, color='green', marker='o', linestyle='None')

plt.show()You can save the figure using the savefig() method.

Remember to save the figure before calling

plt.show() otherwise the figure would be empty.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(5,5)

ax.plot(x, y, color='green', marker='o', linestyle='None')

output_folder = 'output'

output_path = os.path.join(output_folder, 'simple.png')

plt.savefig(output_path)

plt.show()

Matplotlib provides many specialized functions for different types of

plots. scatter() for Scatter Charts, bar() for

Bar Charts and so on. You can use them directly, but in practice they

are used via higher-level libraries like pandas. In the

next section, we will see how to create such charts.

Exercise

Create a plot that displays the 2 given points with their x,y coordinates with different symbology.

point1: Plot it with green color and a triangle marker.point2: Plot it with red color and a circle marker.

Use the code block as your starting point and refer to matplotlib.pyplot.plot documentation for help.

Hint: You can call

plot()multiple times to add new data to the same Axes.

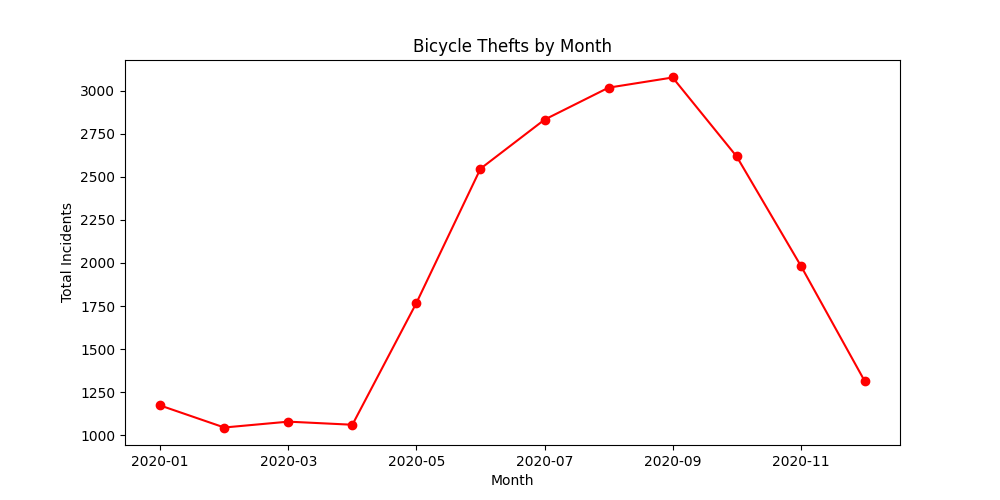

Creating Charts

Overview

Pandas allows you to read structured datasets and visualize them

using the plot() method. By default, Pandas uses

matplotlib to create the plots.

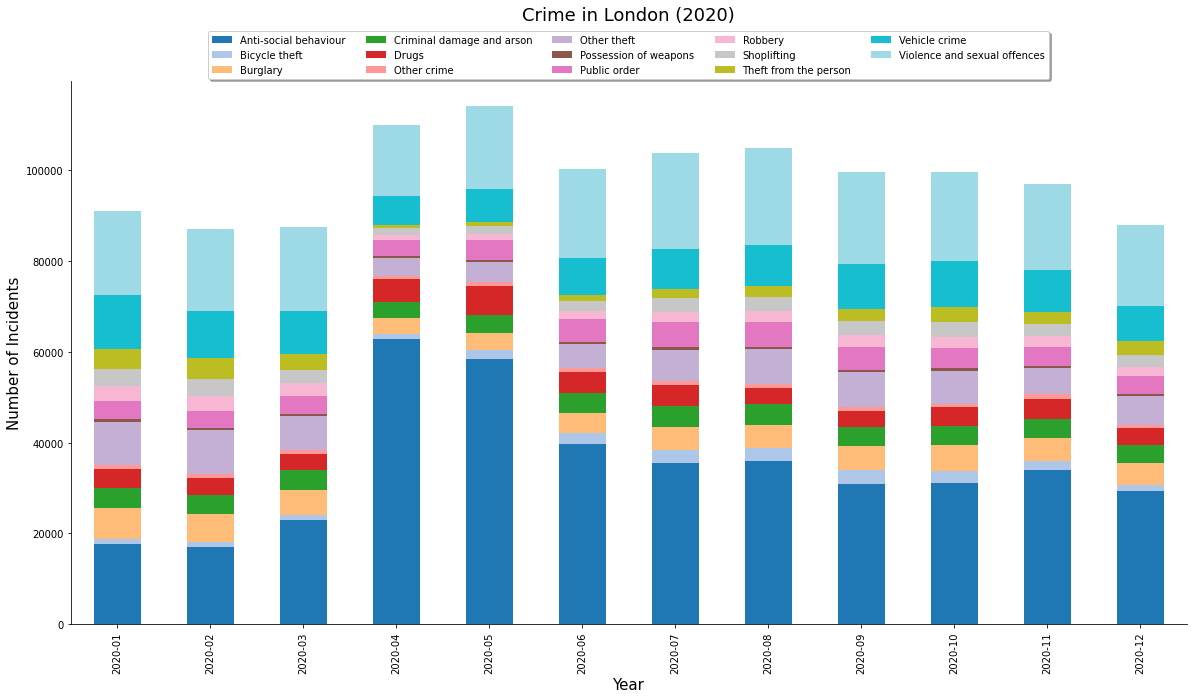

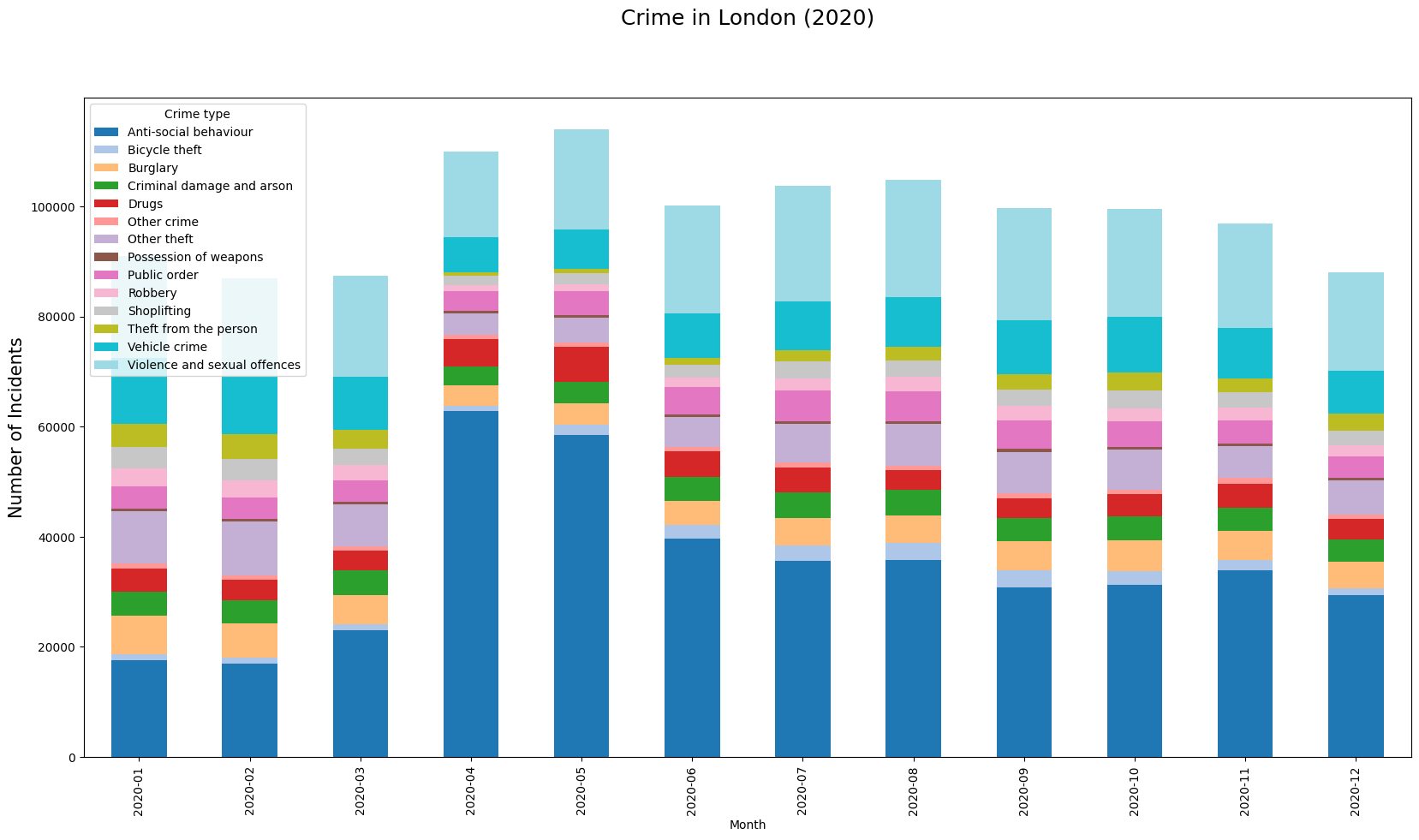

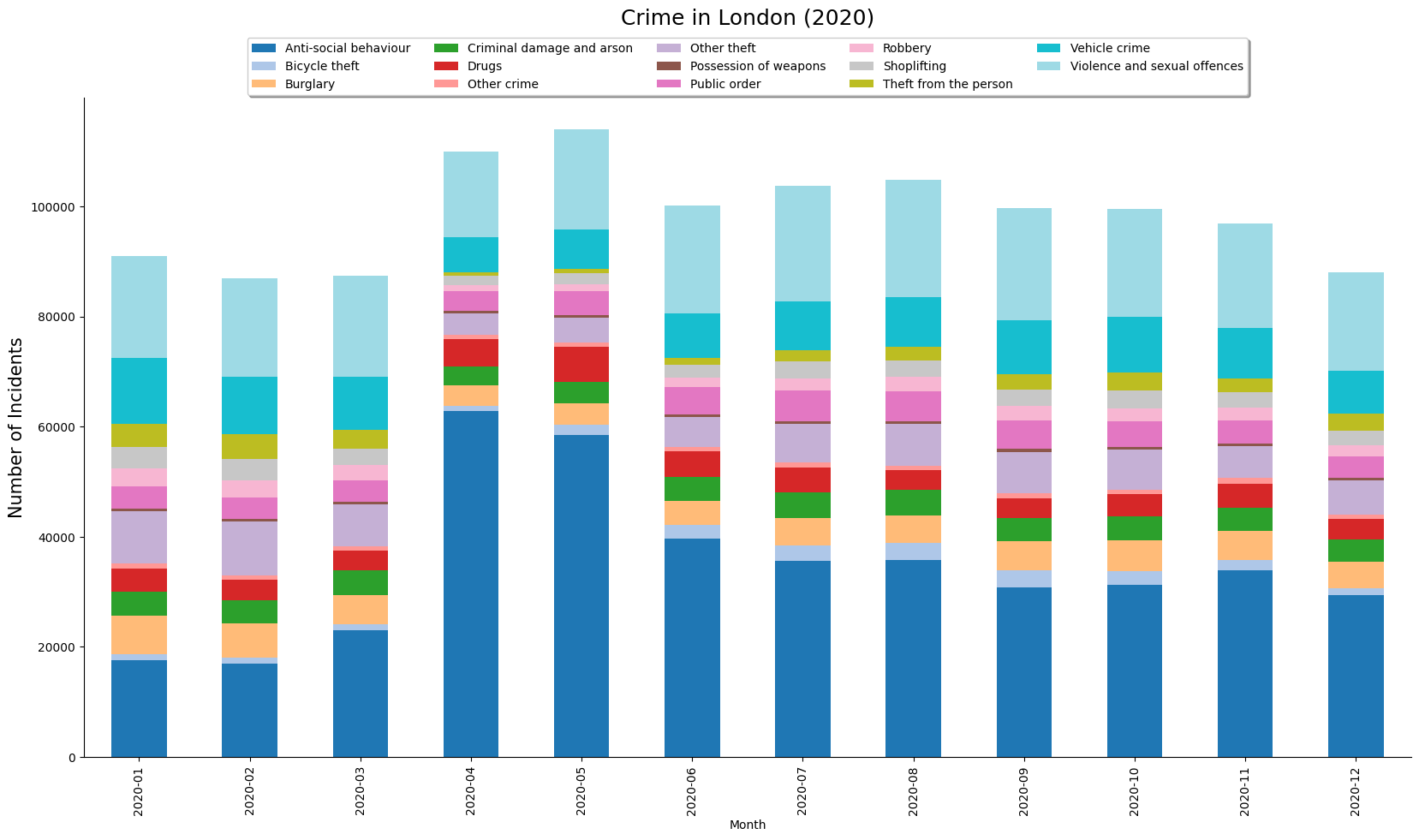

In this notebook, we will take work with open dataset of crime in London.

Setup and Data Download

The following blocks of code will install the required packages and download the datasets to your Colab environment.

data_folder = 'data'

output_folder = 'output'

if not os.path.exists(data_folder):

os.mkdir(data_folder)

if not os.path.exists(output_folder):

os.mkdir(output_folder)def download(url):

filename = os.path.join(data_folder, os.path.basename(url))

if not os.path.exists(filename):

with requests.get(url, stream=True, allow_redirects=True) as r:

with open(filename, 'wb') as f:

for chunk in r.iter_content(chunk_size=8192):

f.write(chunk)

print('Downloaded', filename)We have 12 different CSV files containing crime data for each month of 2020. We download each of them to the data folder.

files = [

'2020-01-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-02-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-03-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-04-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-05-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-06-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-07-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-08-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-09-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-10-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-11-metropolitan-street.csv',

'2020-12-metropolitan-street.csv'

]

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/' \

'download/police.uk/'

for f in files:

url = os.path.join(data_url + f)

download(url)It will be helpful to merge all 12 CSV files into a single dataframe.

We can use pd.concat() to merge a list of dataframes.

dataframe_list = []

for f in files:

filepath = os.path.join(data_folder, f)

df = pd.read_csv(filepath)

dataframe_list.append(df)

merged_df = pd.concat(dataframe_list)The resulting dataframe consists of over 1 million records of various crimes recorded in London in the year 2020.

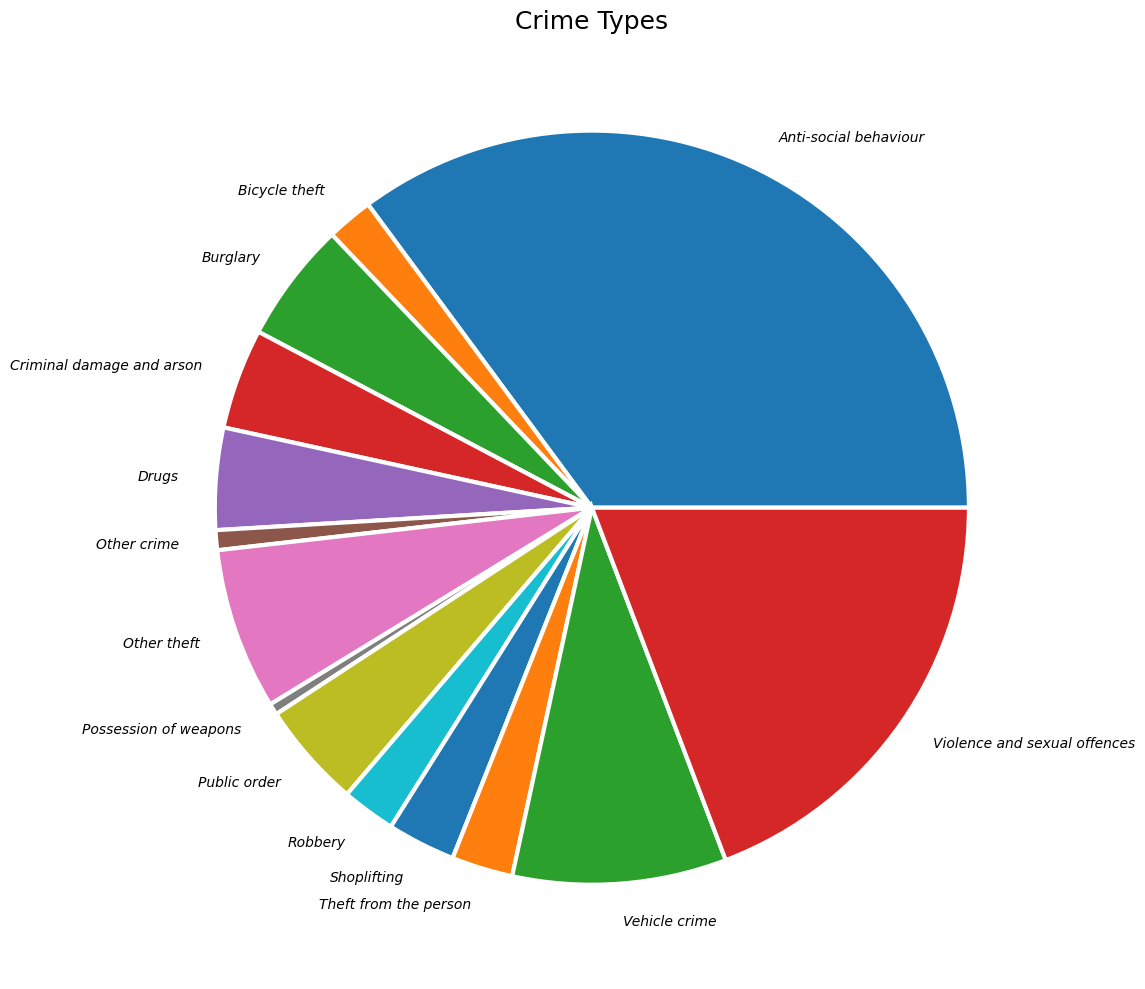

Create a Pie-Chart

Let’s create a pie-chart showing the distribution of different types

of crime. Pandas groupby() function allows us to calculate

group statistics.

We now uses the plot() method to create the chart. This

method is a wrapper around matplotlib and can accept

supported arguments from it.

Reference: pandas.DataFrame.plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,10)

type_counts.plot(kind='pie', ax=ax)

plt.show()Let’s customize the chart. First we use set_title()

method to add a title to the chart and set_ylabel() to

remove the empty y-axis label. Lastly, we use the

plt.tight_layout() to remove the extra whitespace around

the plot.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,10)

type_counts.plot(kind='pie', ax=ax)

ax.set_title('Crime Types', fontsize = 18)

ax.set_ylabel('')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Matplotlib plots offer unlimited possibilities to customize your charts. Let’s see some of the options available to customize the pie-chart.

wedgeprops: Customize the look of each ‘wedge’ of the pie.textprops: Set the text properties of labels.

Reference: matplotlib.pyplot.pie

wedgeprops={'linewidth': 3, 'edgecolor': 'white'}

textprops= {'fontsize': 10, 'fontstyle': 'italic'}

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,10)

type_counts.plot(kind='pie', ax=ax,

wedgeprops=wedgeprops,

textprops=textprops

)

ax.set_title('Crime Types', fontsize = 18)

ax.set_ylabel('')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

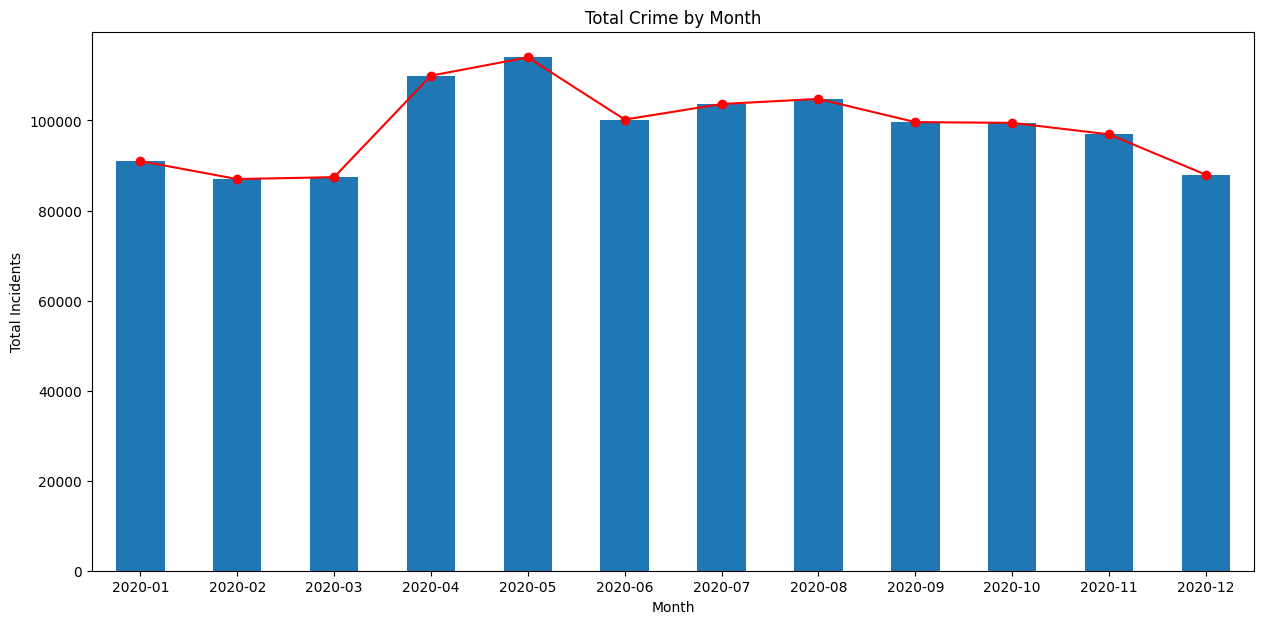

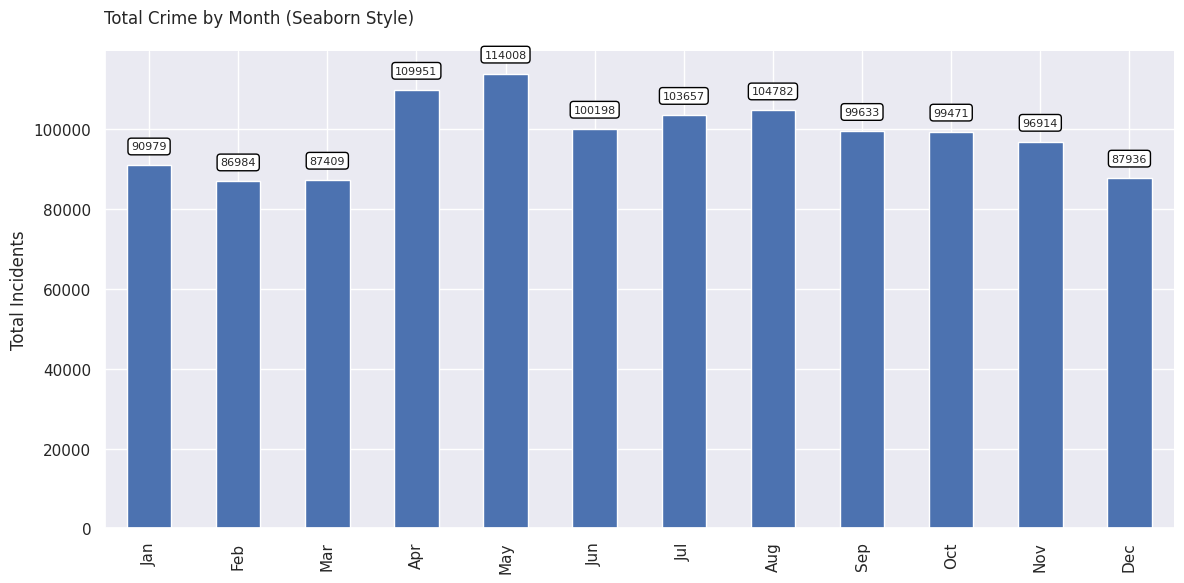

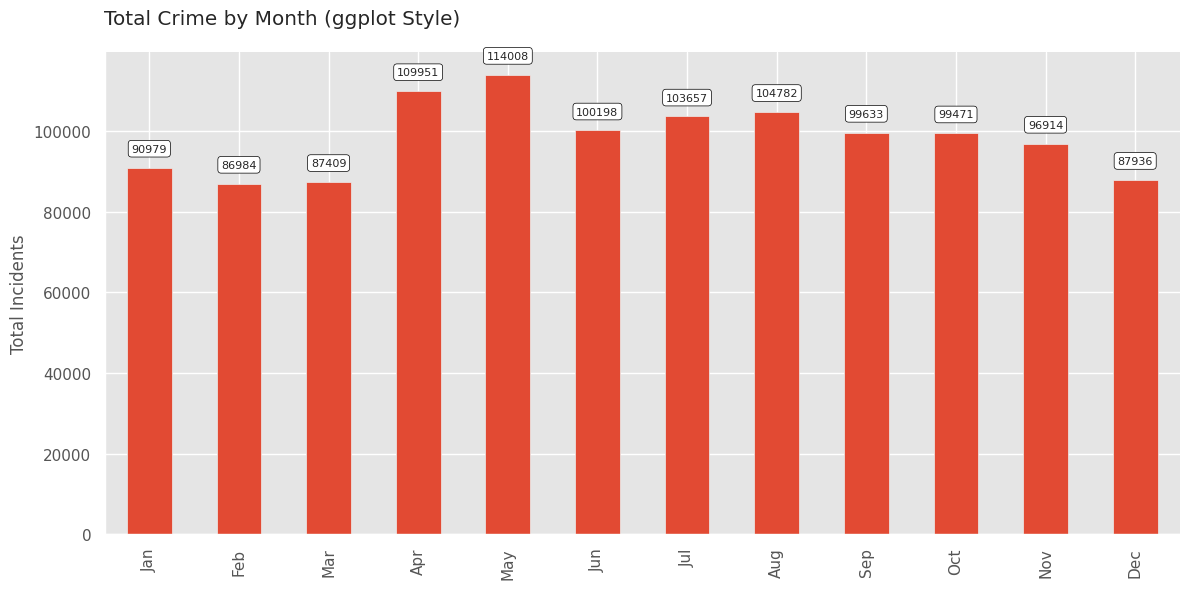

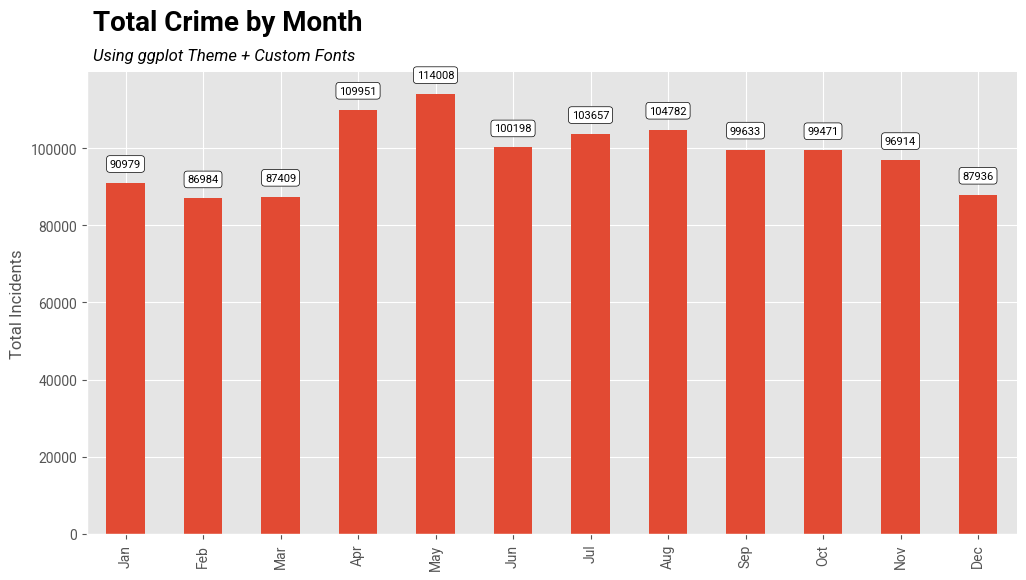

Create a Bar Chart

We can also chart the trend of crime over the year. For this, let’s group the data by month.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,7)

monthly_counts.plot(kind='bar', ax=ax)

plt.show()As we learnt earlier, we can add multiple plots on the same Axes. We

can add a line chart along with the bar chart

to show the trendline as well. Lastly we add the titles and axis labels

to finish the chart.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,7)

monthly_counts.plot(kind='bar', ax=ax)

monthly_counts.plot(kind='line', ax=ax, color='red', marker='o')

ax.set_title('Total Crime by Month')

ax.set_ylabel('Total Incidents')

plt.show()

Creating Maps

Overview

Similar to Pandas, GeoPandas has a plot() method that

can plot geospatial data using Matplotlib.

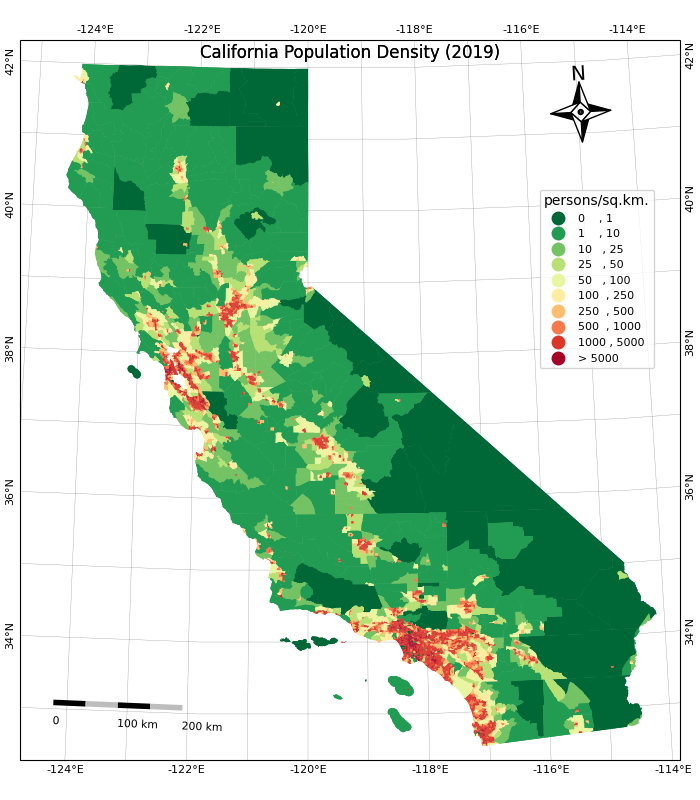

We will work with census data to create a choropleth map of population density. We will start with a shapefile of census tracts, and join it with tabular data to get a GeoDataframe with census tract geometry and correponding populations.

Setup and Data Download

The following blocks of code will install the required packages and download the datasets to your Colab environment.

import geopandas as gpd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import os

import pandas as pd

import requestsdata_folder = 'data'

output_folder = 'output'

if not os.path.exists(data_folder):

os.mkdir(data_folder)

if not os.path.exists(output_folder):

os.mkdir(output_folder)def download(url):

filename = os.path.join(data_folder, os.path.basename(url))

if not os.path.exists(filename):

with requests.get(url, stream=True, allow_redirects=True) as r:

with open(filename, 'wb') as f:

for chunk in r.iter_content(chunk_size=8192):

f.write(chunk)

print('Downloaded', filename)We will download the the census tracts shapefile and a CSV file containing a variety of population statistics for each tract.

shapefile_name = 'tl_2019_06_tract'

shapefile_exts = ['.shp', '.shx', '.dbf', '.prj']

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/' \

'download/census/'

for ext in shapefile_exts:

url = data_url + shapefile_name + ext

download(url)

csv_name = 'ACSST5Y2019.S0101_data.csv'

download(data_url + csv_name)Data Pre-Processing

Let’s read the census tracts shapefile and the CSV file containing population counts.

shapefile_path = os.path.join(data_folder, shapefile_name + '.shp')

tracts = gpd.read_file(shapefile_path)

tractsWe now read the file containing a variety of population statistics

for each tract. We read this file as a Pandas DataFrame. The CSV file

contains an extra row before the header, so we specify

skiprows=[1] to skip reading it.

To join this DataFrame with the GeoDataFrame, we need a column with

unique identifiers. We use the GEOID column and process the

id so they match exactly in both datasets.

filtered = table[['GEO_ID','NAME', 'S0101_C01_001E']]

filtered = filtered.rename(columns = {'S0101_C01_001E': 'Population', 'GEO_ID': 'GEOID'})

filtered['GEOID'] = filtered.GEOID.str[-11:]Finally, we do a table join using the merge method.

For creating a choropleth map, we must normalize the population

counts. US Census Bureau recommends

calculating the population density by dividing the total population by

the land area. The original shapefile contains a column

ALAND with the land area in square kilometers. Using it, we

compute a new column density containing the persons per

square kilometer.

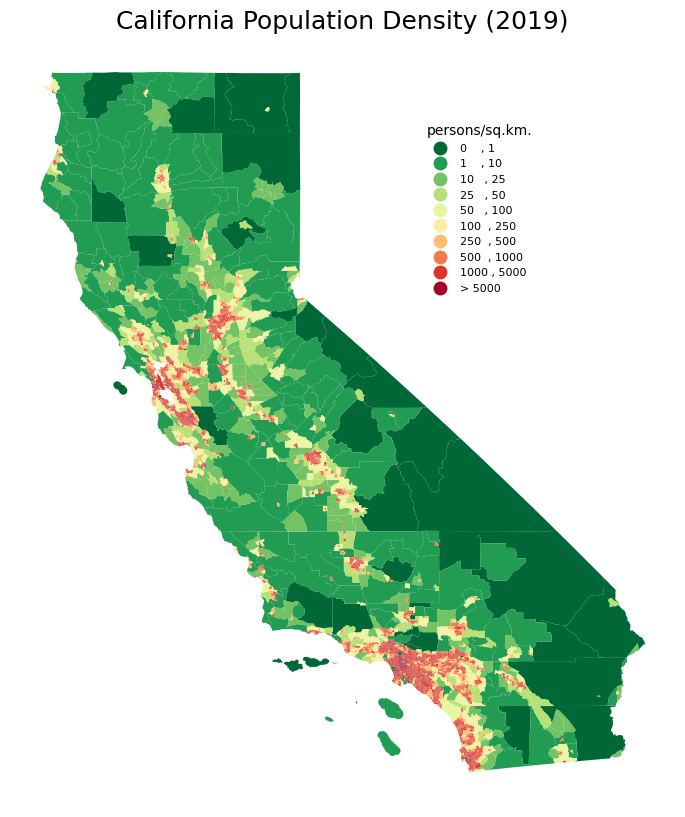

Create a Choropleth Map

The plot() method will render the data to a plot.

Reference: geopandas.GeoDataFrame.plot

You can supply additional style options to change the appearance of

the map. facecolor and edgecolor parameters

are used to determine the fill and outline colors respectively. The

stroke width can be adjusted using the linewidth

parameter.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(10,10)

gdf.plot(ax=ax, facecolor='#f0f0f0', edgecolor='#de2d26', linewidth=0.5)

plt.show()We have the population density for each tract in the

density column. We can assign a color to each polygon based

on the value in this column - resulting in a choropleth map.

Additionally, we need to specify a color ramp using cmap

and classification scheme using scheme. The classification

schedule will determine how the continuous data will be classified into

discrete bins.

Tip: You can add

_rto any color ramp name to get a reversed version of that ramp.

References: - Matplotlib Colormaps - Mapclassify Classification Schemes

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(10,10)

gdf.plot(ax=ax, column='density', cmap='RdYlGn_r', scheme='quantiles')

plt.show()Instead of the class breaks being determined by the classification

scheme, we can also manually specify the ranges. This is preferable so

we can have a human-interpretable legend. The legend=True

parameter adds a legend to our plot.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(10,10)

classification_kwds={

'bins': [1,10,25,50,100, 250, 500, 1000, 5000]

}

gdf.plot(ax=ax, column='density', cmap='RdYlGn_r', scheme='User_Defined',

classification_kwds=classification_kwds, legend=True)

plt.show()We can supply legend customization options via the

legend_kwds parameter and adjust the legend position,

formatting of the text, and add a legend title. We can also manually

adjust the legend entries, to give a more legible labels.

legend_kwds= {

'loc': 'upper right',

'bbox_to_anchor': (0.8, 0.9),

'fmt': '{:<5.0f}',

'frameon': False,

'fontsize': 8,

'title': 'persons/sq.km.'

}

classification_kwds={

'bins':[1,10,25,50,100, 250, 500, 1000, 5000]

}

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(10,10)

gdf.plot(ax=ax, column='density', cmap='RdYlGn_r', scheme='User_Defined',

classification_kwds=classification_kwds,

legend=True, legend_kwds=legend_kwds)

ax.set_axis_off()

# Change the last entry in the legend to '>5000'

legend = ax.get_legend()

legend.texts[-1].set_text('> 5000')

plt.show()Once we are happy with the look, we add a title and save the result

as a PNG file. Remember to call plt.savefig() before

showing the plot as the plot gets emptied after being shown.

legend_kwds= {

'loc': 'upper right',

'bbox_to_anchor': (0.8, 0.9),

'fmt': '{:<5.0f}',

'frameon': False,

'fontsize': 8,

'title': 'persons/sq.km.'

}

classification_kwds={

'bins':[1,10,25,50,100, 250, 500, 1000, 5000]

}

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(10,10)

gdf.plot(ax=ax, column='density', cmap='RdYlGn_r', scheme='User_Defined',

classification_kwds=classification_kwds,

legend=True, legend_kwds=legend_kwds)

ax.set_axis_off()

# Change the last entry in the legend to '>5000'

legend = ax.get_legend()

legend.texts[-1].set_text('> 5000')

# Add a title

ax.set_title('California Population Density (2019)', size = 18)

output_path = os.path.join(output_folder, 'california_pop.png')

plt.savefig(output_path, dpi=300)

plt.show()

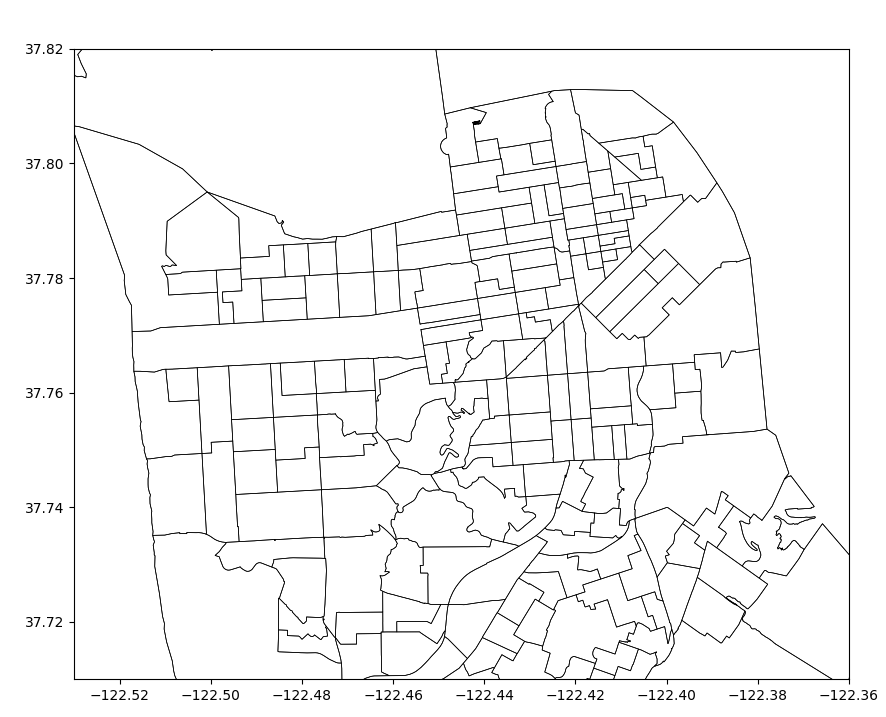

Exercise

- Plot the census tracts geodataframe

tractswith just outlines and no fill color. - Display the map zoomed-in around the San Francisco area between

Latitudes from

37.71to37.82and Longitudes from-122.53to-122.36.

Use the code block below as your starting point.

Hints:

- Set the

facecoloroption to'none'for no fills. Refer to the style_kwds parameter of theplot()method for more details. - Use the

set_xlim()andset_ylim()methods to set the view area of the Axes. Remember that Latitudes are Y-coordinates and Longitudes are X-Coordinates.

Using Basemaps

Overview

Creating geospatial visualizations often require overlaying your data on a basemap. Contextily is a package that allows you to fetch various basemaps from the internet and add them to your plot as static images.

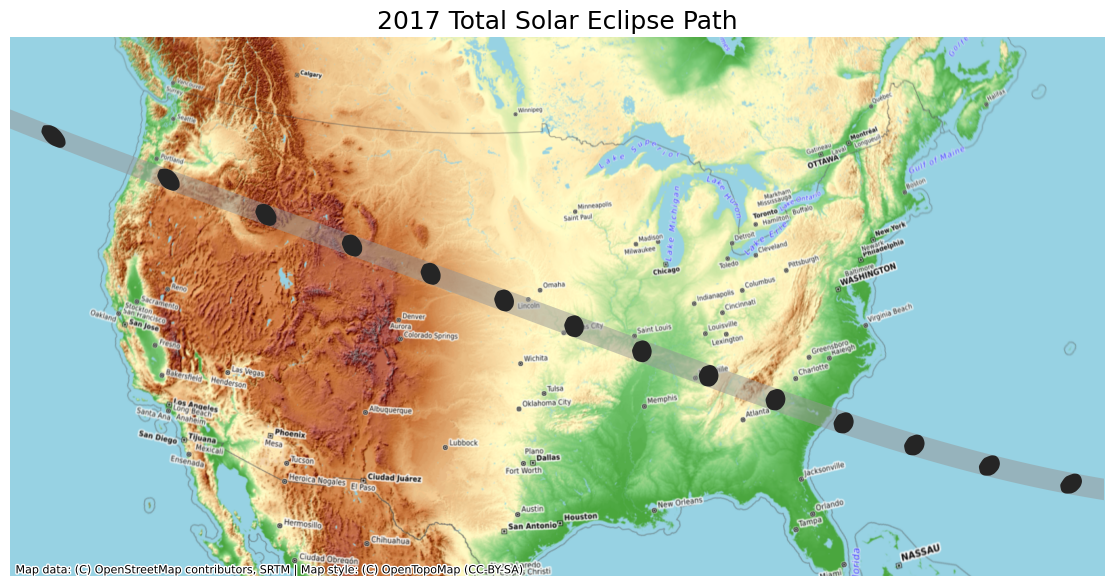

We will learn how to take a shapefile showing the path of the 2017 Solar Eclipse and create a map with a topographic basemap. NASA also provides similar data for other eclipses, including the 2024 Total Solar Eclipse.

Setup and Data Download

The following blocks of code will install the required packages and download the datasets to your Colab environment.

import contextily as cx

import geopandas as gpd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import os

import requests

import shapelydata_folder = 'data'

output_folder = 'output'

if not os.path.exists(data_folder):

os.mkdir(data_folder)

if not os.path.exists(output_folder):

os.mkdir(output_folder)def download(url):

filename = os.path.join(data_folder, os.path.basename(url))

if not os.path.exists(filename):

with requests.get(url, stream=True, allow_redirects=True) as r:

with open(filename, 'wb') as f:

for chunk in r.iter_content(chunk_size=8192):

f.write(chunk)

print('Downloaded', filename)path_shapefile = 'upath17'

umbra_shapefile = 'umbra17'

penumbra_shapefile = 'penum17'

shapefile_exts = ['.shp', '.shx', '.dbf', '.prj']

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/' \

'download/eclipse/'

for shapefile in [path_shapefile, umbra_shapefile, penumbra_shapefile]:

for ext in shapefile_exts:

url = data_url + shapefile + ext

download(url)Data Pre-Processing

Create a Multi-Layer Map

We can show a GeoDataFrame using the plot() method.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,7)

path_gdf.plot(

ax=ax,

facecolor='#969696',

edgecolor='none',

alpha=0.5)

plt.show()To add another layer to our plot, we can simply render another GeoDataFrame on the same Axes.

Add A BaseMap

The visualization is not useful as it is missing context. We want to

overlay this on a basemap to understand where the eclipse was visible

from. We can choose from a variety of basemap tiles. There are over 200

basemap styles included in the library. Let’s see them using the

providers property.

Some of the providers are open-access while others require registration and obtaining an API key. We can filter the list to only open-access providers.

For overlaying the eclipse path, let’s use the OpenTopoMap basemap. We need to specify a CRS for the map. For now, let’s use the CRS of the original shapefile.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,7)

path_gdf.plot(

ax=ax,

facecolor='#969696',

edgecolor='none',

alpha=0.5)

umbra_gdf.plot(

ax=ax,

facecolor='#252525',

edgecolor='none')

cx.add_basemap(

ax,

crs=path_gdf.crs,

source=cx.providers.OpenTopoMap)

plt.show()We can request higher resolution tiles by specifying the

zoom parameter. But increasing zoom level means many more

tiles need to be downloaded. Contextily has some utility functions to

find out the zoom level and corresponding tiles that needs to be

downloaded.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,7)

path_gdf.plot(

ax=ax,

facecolor='#969696',

edgecolor='none',

alpha=0.5)

umbra_gdf.plot(

ax=ax,

facecolor='#252525',

edgecolor='none')

cx.add_basemap(

ax,

crs=path_gdf.crs,

source=cx.providers.OpenTopoMap,

zoom=4)

plt.show()As this eclipse primarily covers the United States, we can create a visualization in a CRS suited for the region. We reproject the layers to the US National Atlas Equal Area projection and set the map extent to the bounds of the continental united states.

crs = 'EPSG:9311'

path_reprojected = path_gdf.to_crs(crs)

umbra_reprojected = umbra_gdf.to_crs(crs)

# Use the bounding box coordinates for continental us

usa = shapely.geometry.box(-125, 24, -66, 49)

usa_gdf = gpd.GeoDataFrame(geometry=[usa], crs='EPSG:4326')

usa_gdf_reprojected = usa_gdf.to_crs(crs)

bounds = usa_gdf_reprojected.total_boundsfig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,7)

# Set the bounds

ax.set_xlim(bounds[0], bounds[2])

ax.set_ylim(bounds[1], bounds[3])

path_reprojected.plot(

ax=ax,

facecolor='#969696',

edgecolor='none',

alpha=0.5)

umbra_reprojected.plot(

ax=ax,

facecolor='#252525',

edgecolor='none')

cx.add_basemap(

ax,

crs=path_reprojected.crs,

source=cx.providers.OpenTopoMap,

zoom=5)

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_title('2017 Total Solar Eclipse Path', size = 18)

plt.show()

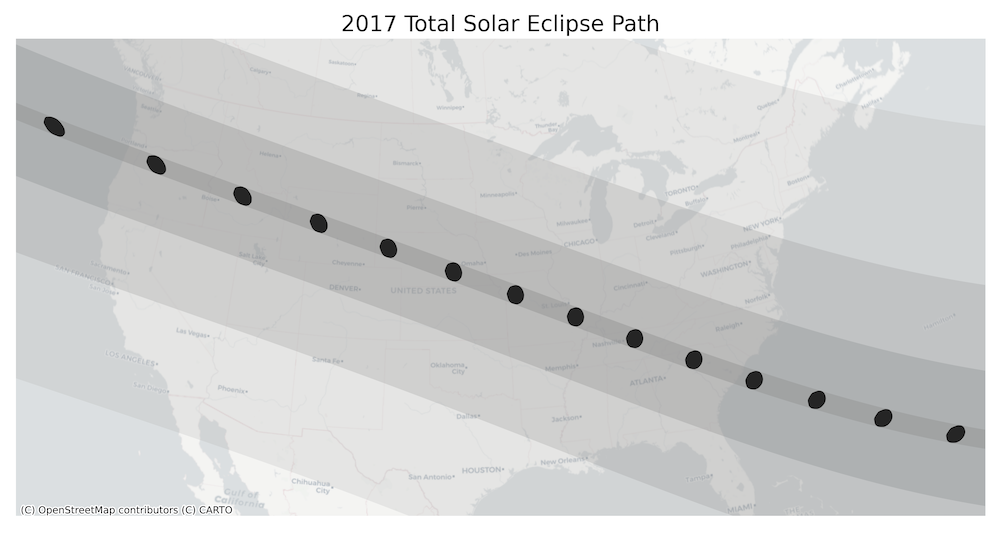

Exercise

- Our eclipse dataset also contains polygons for penumbra contours.

Add them to the visualization. This layer has a column

Obscurthat contains the obscuration value (the fraction of the Sun’s area covered by the Moon). Style the contours by the obscuration value and add it to the map. - Instead of the OpenTopoMap, create a visualization using another

basemap. Some options to try are

Esri.WorldTerrain,CartoDB.PositronandUSGS.USTopo.

The code below reads and re-projects the penumbra shapefile.

penumbra_shapefile_path = os.path.join(

data_folder, penumbra_shapefile + '.shp')

penumbra_gdf = gpd.read_file(penumbra_shapefile_path)

penumbra_reprojected = penumbra_gdf.to_crs(crs)

penumbra_reprojectedYou can use the code block below for creating the visualization. It

render the Penumbra polygons by the Obsur column using a

transparency value of 0.2 (20%). Complete the exercise by

rendering the Path and Umbra layers on top and add a basemap of your

choice.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(15,7)

# Set the bounds

ax.set_xlim(bounds[0], bounds[2])

ax.set_ylim(bounds[1], bounds[3])

penumbra_reprojected.plot(

ax=ax,

column='Obscur',

cmap='Greys',

linewidth=1,

alpha=0.2

)

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_title('2017 Total Solar Eclipse Path', size = 18)

plt.show()XArray Basics

Overview

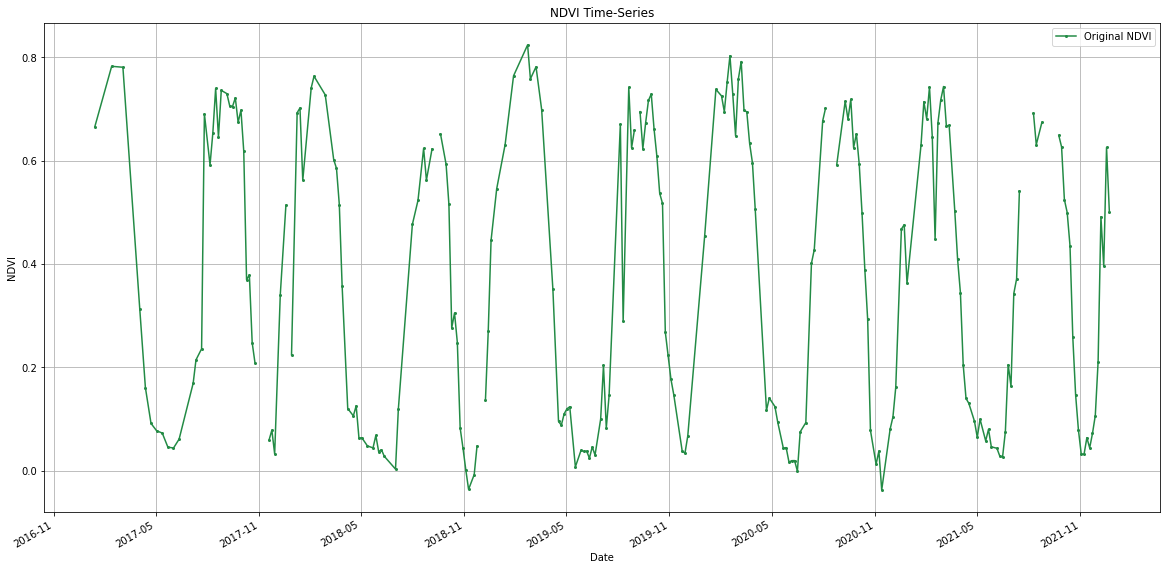

Xarray is an evolution of rasterio and is inspired by libraries like pandas to work with raster datasets. It is particularly suited for working with multi-dimensional time-series raster datasets. It also integrates tightly with dask that allows one to scale raster data processing using parallel computing. XArray provides Plotting Functions based on Matplotlib.

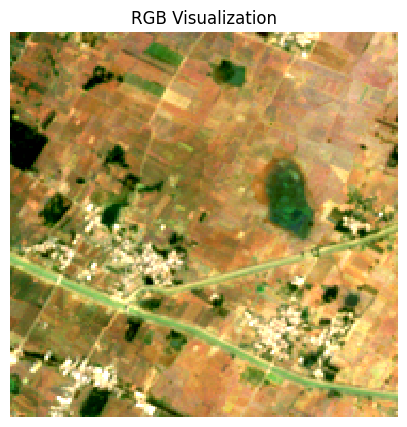

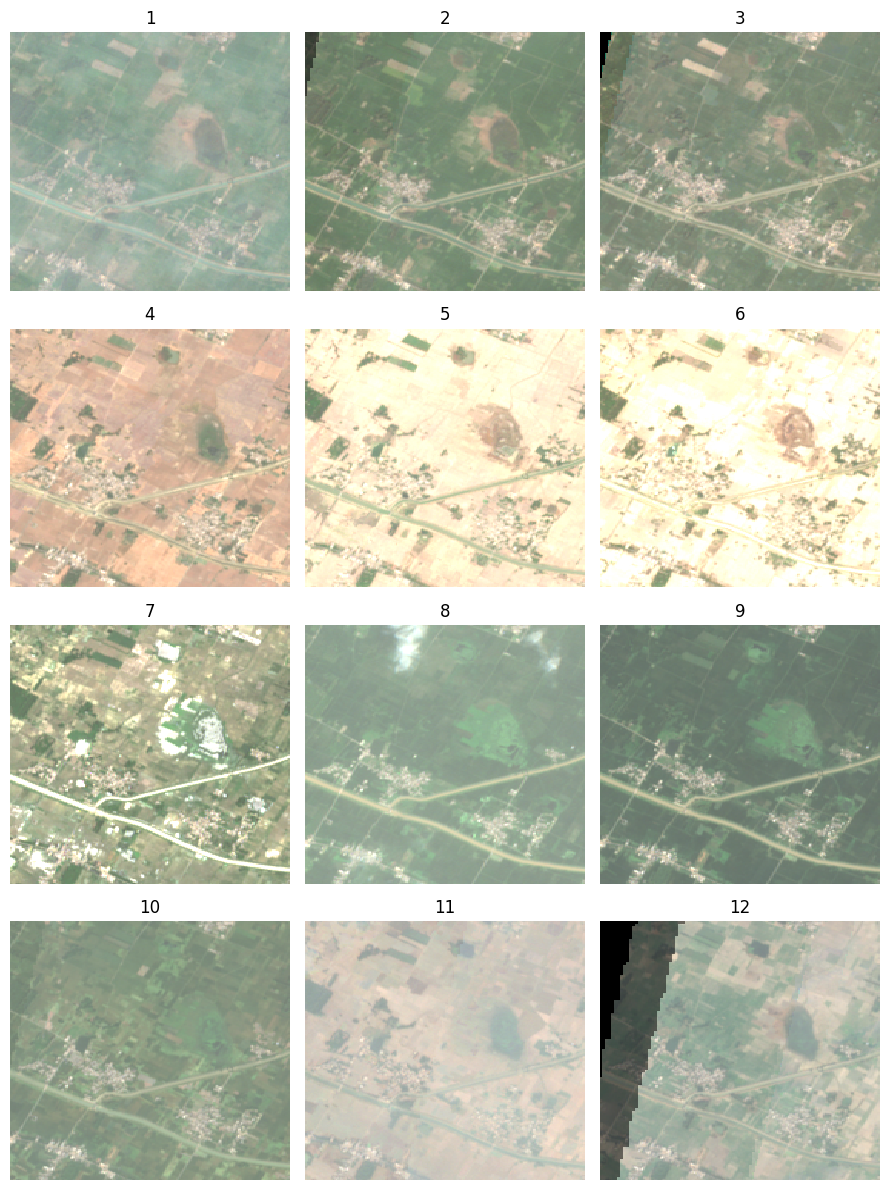

In this section, we will learn about XArray basics and learn how to work with a time-series of Sentinel-2 satellite imagery to create and visualize a median composite image.

Setup and Data Download

The following blocks of code will install the required packages and download the datasets to your Colab environment.

%%capture

if 'google.colab' in str(get_ipython()):

!pip install pystac-client odc-stac rioxarray daskGet Satellite Imagery using STAC API

We define a location and time of interest to get some satellite imagery.

Let’s use Element84 search endpoint to look for items from the sentinel-2-l2a collection on AWS.

catalog = pystac_client.Client.open(

'https://earth-search.aws.element84.com/v1')

# Define a small bounding box around the chosen point

km2deg = 1.0 / 111

x, y = (longitude, latitude)

r = 1 * km2deg # radius in degrees

bbox = (x - r, y - r, x + r, y + r)

search = catalog.search(

collections=['sentinel-2-c1-l2a'],

bbox=bbox,

datetime=f'{year}',

query={'eo:cloud_cover': {'lt': 30}},

)

items = search.item_collection()Load the matching images as a XArray Dataset.

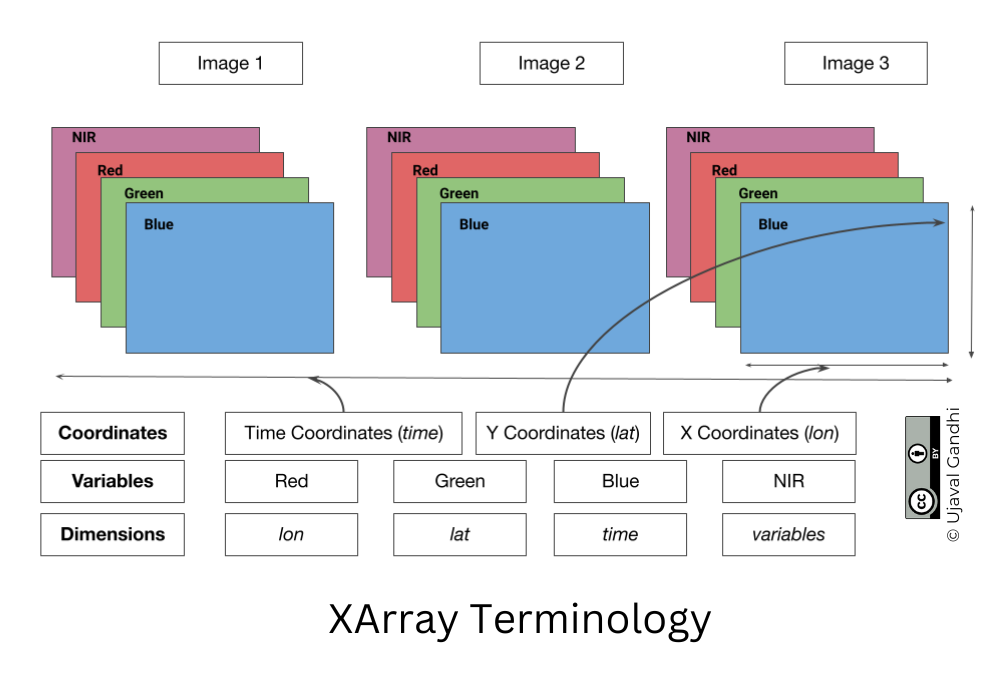

XArray Terminology

We now have a xarray.Dataset object. Let’s understand

what is contained in a Dataset.

- Variables: This is similar to a band in a raster dataset. Each variable contains an array of values.

- Dimensions: This is similar to number of array axes.

- Coordinates: These are the labels for values in each dimension.

- Attributes: This is the metadata associated with the dataset.

A Dataset consists of one or more xarray.DataArray

object. This is the main object that consists of a single variable with

dimension names, coordinates and attributes. You can access each

variable using dataset.variable_name syntax.

Selecting Data

XArray provides a very powerful way to select subsets of data, using

similar framework as Pandas. Similar to Panda’s loc and

iloc methods, XArray provides sel and

isel methods. Since DataArray dimensions have names, these

methods allow you to specify which dimension to query.

Let’s select the temperature anomany values for the last time step.

Since we know the index (-1) of the datam we can use isel

method.

You can call .values on a DataArray to get an array of

the values.

You can query for a values at using multiple dimensions.

We can also specify a value to query using the sel()

method.

Let’s see what are the values of time variable.

We can query using the value of a coordinate using the

sel() method.

The sel() method also support nearest neighbor lookups.

This is useful when you do not know the exact label of the dimension,

but want to find the closest one.

Tip: You can use

interp()instead ofsel()to interpolate the value instead of closest lookup.

The sel() method also allows specifying range of values

using Python’s built-in slice() function. The code below

will select all observations during January 2023.

Aggregating Data

A very-powerful feature of XArray is the ability to easily aggregate data across dimensions - making it ideal for many remote sensing analysis. Let’s create a median composite from all the individual images.

We apply the .median() aggregation across the

time dimension.

Visualizing Data

XArray provides a plot.imshow() method based on

Matplotlib to plot DataArrays.

Reference : xarray.plot.imshow

To visualize our Dataset, we first convert it to a DataArray using

the to_array() method. All the variables will be converted

to a new dimension. Since our variables are image bands, we give the

name of the new dimesion as band.

The easy way to visualize the data without the outliers is to pass

the parameter robust=True. This will use the 2nd and 98th

percentiles of the data to compute the color limits. We also specify the

set_aspect('equal') to ensure the original aspect ratio is

maintained and the image is not stretched.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(5,5)

median_da.sel(band=['red', 'green', 'blue']).plot.imshow(

ax=ax,

robust=True)

ax.set_title('RGB Visualization')

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set_aspect('equal')

plt.show()

We can save the resulting median compositeas a multi-band GeoTIFF file.

Exercise

Display the median composite for the month of May.

The snippet below takes our time-series and aggregate it to a monthly

median composites groupby() method.

You now have a new dimension named month. Start your

exercise by first converting the Dataset to a DataArray. Then extract

the data for the chosen month using sel() method and plot

it.

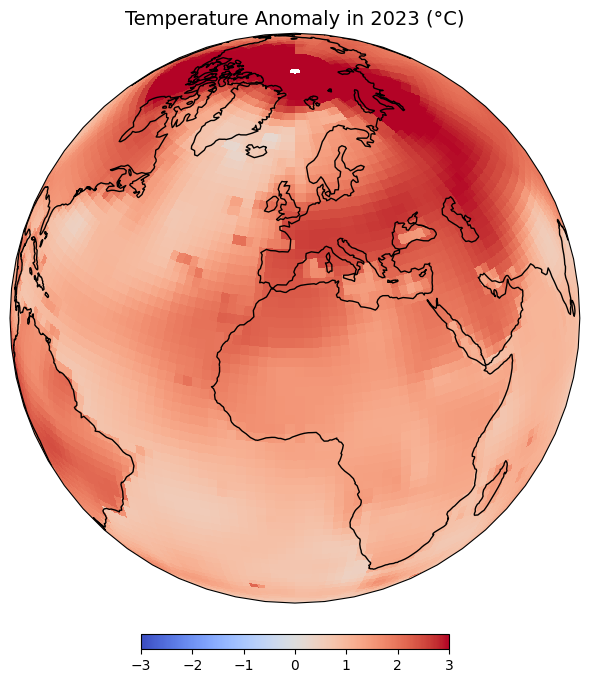

Mapping Gridded Datasets

Overview

In this section, we will take the Gridded Monthly Temperature Anomaly Data from 1880-present from GISTEMP and visualize the temperature anomaly for any year.

Setup and Data Download

The following blocks of code will install the required packages and download the datasets to your Colab environment.

import cartopy

import cartopy.crs as ccrs

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import xarray as xrdata_folder = 'data'

output_folder = 'output'

if not os.path.exists(data_folder):

os.mkdir(data_folder)

if not os.path.exists(output_folder):

os.mkdir(output_folder)def download(url):

filename = os.path.join(data_folder, os.path.basename(url))

if not os.path.exists(filename):

from urllib.request import urlretrieve

local, _ = urlretrieve(url, filename)

print('Downloaded ' + local)

filename = 'gistemp1200_GHCNv4_ERSSTv5.nc'

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/' \

'download/gistemp/'

download(data_url + filename)Data Pre-Processing

We read the data using XArray and select the

tempanomaly variable.

file_path = os.path.join(data_folder, filename)

ds = xr.open_dataset(file_path)

da = ds.tempanomaly

daWe have monthly anomalies from 1880-present. Let’s aggregate it to mean yealy anomalies.

Plotting using Matplotlib

Let’s extract the data for one of the years.

We can use the .sel() method to query using the value of

the year dimension.

We can customize the plot using Matplotlib’s options.

Plotting using CartoPy

To create more informative map visualization, we need to reproject this grid to another projection. CartoPy supports a wide range of projections and can plot them using matplotlib. CartoPy creates a GeoAxes object and replaces the default Axes with it. This allows you to plot the data on a specified projection.

We start as usual by create a subplot but specify an additional argument to set the CRS from CartoPy.

Reference: CartoPy List of Projections

projection = ccrs.Orthographic(0, 30)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, subplot_kw={'projection': projection})

fig.set_size_inches(5,5)

anomaly.plot.imshow(ax=ax,

vmin=-3, vmax=3, cmap='coolwarm',

transform=ccrs.PlateCarree())

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()We can further customize the map by adjusting the colorbar.

Reference: matplotlib.pyplot.colorbar

projection = ccrs.Orthographic(0, 30)

cbar_kwargs = {

'orientation':'horizontal',

'fraction': 0.025,

'pad': 0.05,

'extend':'neither'

}

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, subplot_kw={'projection': projection})

fig.set_size_inches(8, 8)

anomaly.plot.imshow(

ax=ax,

vmin=-3, vmax=3, cmap='coolwarm',

transform=ccrs.PlateCarree(),

add_labels=False,

cbar_kwargs=cbar_kwargs)

ax.coastlines()

plt.title(f'Temperature Anomaly in {year} (°K)', fontsize = 14)

output_folder = 'output'

output_path = os.path.join(output_folder, 'anomaly.jpg')

plt.savefig(output_path, dpi=300)

plt.show()

Exercise

Display the map in the Equal Earth projection.

Visualizing Rasters

Overview

In the previous notebook, we learnt how to use Xarray to work with gridded datasets. XArray is also well suited to work with georeferenced rasters - such as satellite imagery, population grids, or elevation data.rioxarray is an extension of xarray that makes it easy to work with geospatial rasters.

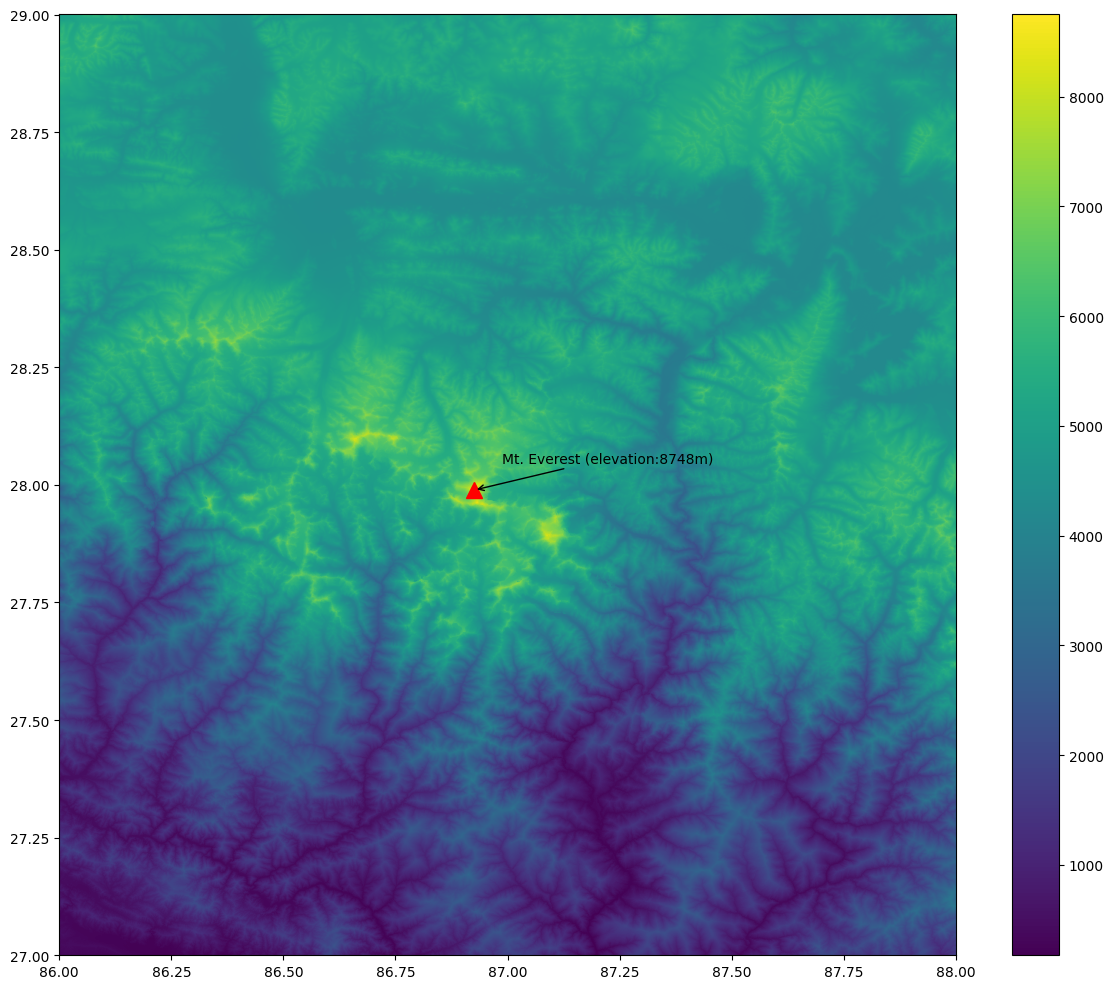

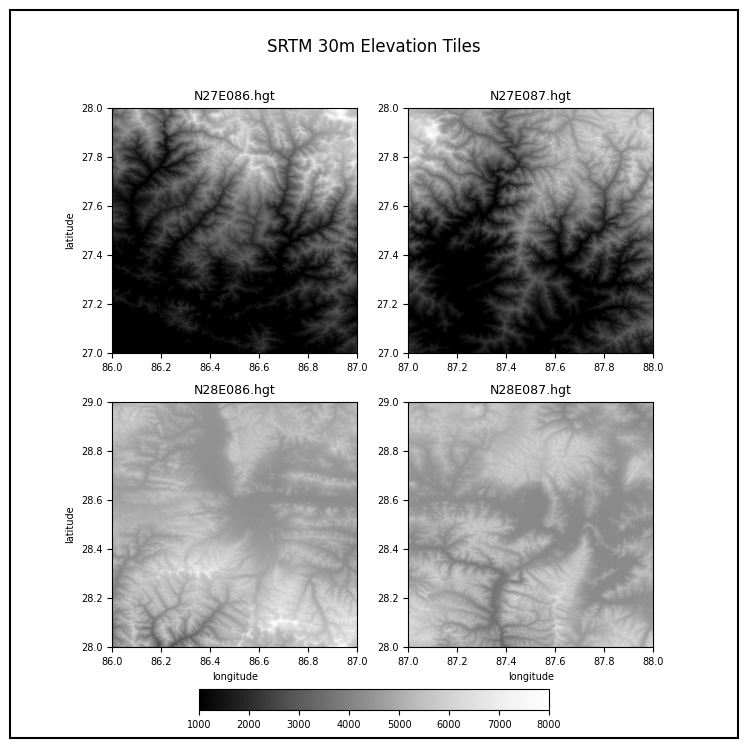

In this section, we will take 4 individual SRTM tiles around the Mt.

Everest region and merge them to a single GeoTiff using RasterIO. We

will also use matplotlib to add labels to the final map

using annonations.

Setup and Data Download

The following blocks of code will install the required packages and download the datasets to your Colab environment.

By convention, rioxarray is imported as

rxr.

Remember to always import

rioxarrayeven if you are using sub-modules such asmerge_arrays. Importingrioxarrayactivates therioaccessor which is required for all operations.

import os

import rioxarray as rxr

from rioxarray.merge import merge_arrays

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltdata_folder = 'data'

output_folder = 'output'

if not os.path.exists(data_folder):

os.mkdir(data_folder)

if not os.path.exists(output_folder):

os.mkdir(output_folder)def download(url):

filename = os.path.join(data_folder, os.path.basename(url))

if not os.path.exists(filename):

from urllib.request import urlretrieve

local, _ = urlretrieve(url, filename)

print('Downloaded ' + local)

srtm_tiles = [

'N27E086.hgt',

'N27E087.hgt',

'N28E086.hgt',

'N28E087.hgt'

]

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/' \

'download/srtm/'

for tile in srtm_tiles:

url = f'{data_url}/{tile}'

download(url)Rioxarray Basics

The open_rasterio() method from rioxarray

is able to read any data source supported by. the rasterio

library. Let’s open a single SRTM tile using rioxarray.

filename = 'N28E087.hgt'

file_path = os.path.join(data_folder, filename)

rds = rxr.open_rasterio(file_path)The result is a xarray.DataArray object.

You can access the pixel values using the values

property which returns the array’s data as a numpy array.

A xarray.DataArray object also contains 1 or more

coordinates. Each coordinate is a 1-dimensional array

representing values along one of the data axes. In case of the 1-band

SRTM elevation data, we have 3 coordinates - x,

y and band.

The raster metadata is stored in the rio

accessor. This is enabled by the rioxarray library which

provides geospatial functions on top of xarray.

Plotting Multiple Rasters

Open each source file using open_rasterio() method and

store the resulting datasets in a list.

datasets = []

for tile in srtm_tiles:

path = os.path.join(data_folder, tile)

rds = rxr.open_rasterio(path)

band = rds.sel(band=1)

datasets.append(band)You can visualize any DataArray object by calling

plot() method. Here we create a subplot with 1 row and 4

columns. The subplots() method will return a list of Axes

that we can use to render each of the source SRTM rasters. For plots

with multiple columns, the Axes will be a nested list. To easily iterate

over it, we can use .flat which returns a 1D iterator on

the axes.

While plotting the data, we can use the cmap option to

specify a color ramp. Here we are using the built-in Greys

ramp. Appending **_r** gives us the inverted ramp with blacks

representing lower elevation values. When plotting on multiple Axes, it

is useful to specify set_aspect('equal') so the aspect raio

of the plot is maintained even if there is not enough space.

Merging Rasters

Now that you understand the basic data structure of xarray

and the rio extension, let’s use it to process some data. We

will take 4 individual SRTM tiles and merge them to a single GeoTiff.

You will note that rioxarray handles the CRS and transform

much better - taking care of internal details and providing a simple

API.

We will use the merge_arrays() method from the

rioxarray.merge module to merge the rasters. We can also

specify an optional method that controls how overlapping

tiles are merged. Here we have chosen first which takes the

value of the first raster in the overlapping region.

Reference: merge_arrays()

We can now visualize the merged raster.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

fig.set_size_inches(12, 10)

merged.plot.imshow(ax=ax, cmap='Greys_r')

ax.set_title('merged')

plt.show()We can save the resulting raster in any format supported by GDAL

using the to_raster() method. Let’s save this as a Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF

(COG).

Annotating Plots

Sometime it is helpful to add annotations on your plot to highlight a feature or add a text label. In this section we will learn how to use the annotate the DEM to show the location and elevation of Mt. Everest.

First, we locate the coordinates of the maximum elevation in the

merged DataArray using the max() function. We

can then use where() function to filter the elements where

the value equals the maximum elevation. Lastly, we run

squeeze() to remove the extra empty dimension from the

result.

References:

We now extract the x,y coordinates and the value of the maximum elevation.

max_x = max_da.x.values

max_y = max_da.y.values

max_elev = int(max_da.values)

print(max_x, max_y, max_elev)Now we plot the merged raster and annotate it using the

annotate() function.

Reference: matplotlib.pyplot.annotate

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(12, 10)

merged.plot.imshow(ax=ax, cmap='viridis', add_labels=False)

ax.plot(max_x, max_y, color='red', marker='^', markersize=11)

ax.annotate(f'Mt. Everest (elevation:{max_elev}m)',

xy=(max_x, max_y), xycoords='data',

xytext=(20, 20), textcoords='offset points',

arrowprops={'arrowstyle':'->', 'color':'black'}

)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

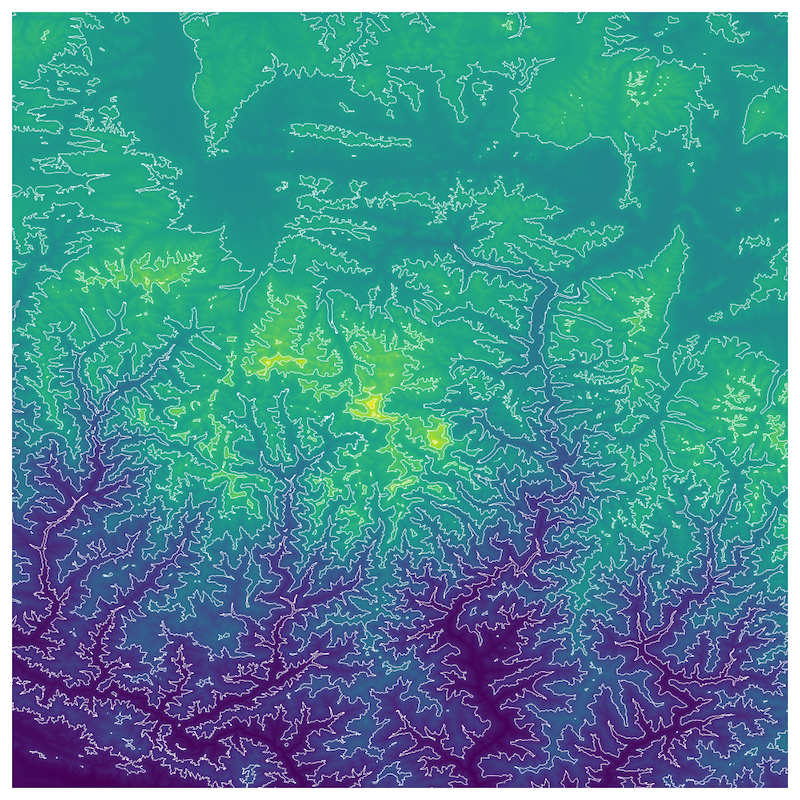

Exercise

Add contours to the elevation plot below.

Start with the code snippet below and use the xarray.plot.contour

function to render the contours

Hint: Use the options colors=white and

levels=10.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

fig.set_size_inches(10, 10)

merged.plot.imshow(

ax=ax,

cmap='viridis',

add_labels=False,

add_colorbar=False)

ax.set_axis_off()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Assignment

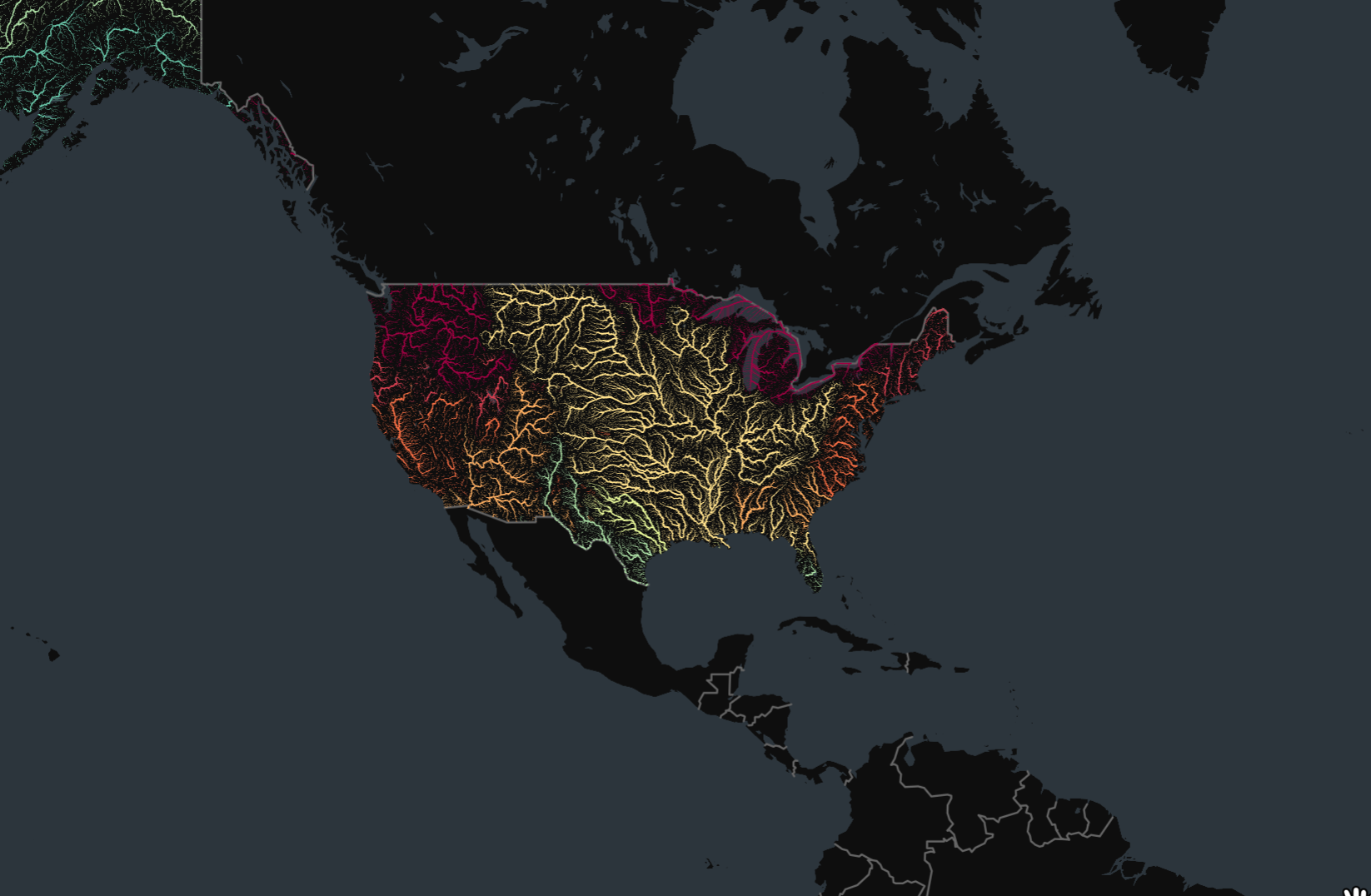

Overview

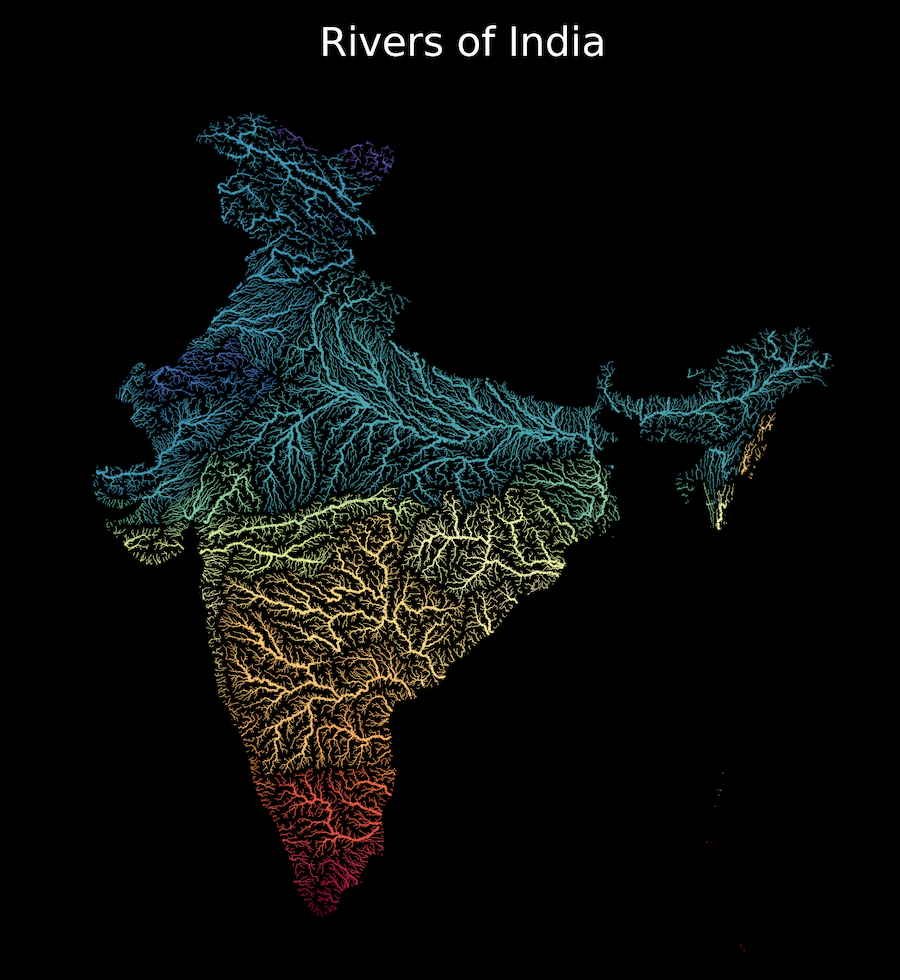

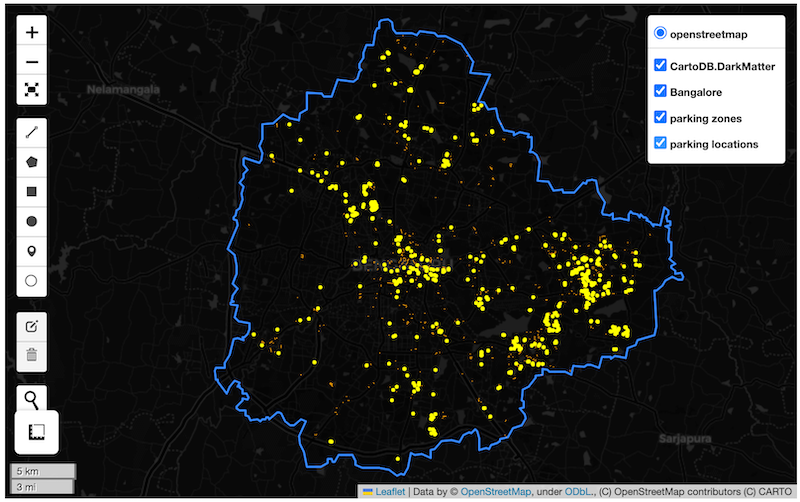

Your assignment is to create a colorized river basin map for your country using the HydroRIVERS data.

This notebook contains code to download and pre-process the data. Your task is to plot the rivers using Matplotlib and achieve a unique style shown below.

Setup and Data Download

data_folder = 'data'

output_folder = 'output'

if not os.path.exists(data_folder):

os.mkdir(data_folder)

if not os.path.exists(output_folder):

os.mkdir(output_folder)def download(url):

filename = os.path.join(data_folder, os.path.basename(url))

if not os.path.exists(filename):

with requests.get(url, stream=True, allow_redirects=True) as r:

with open(filename, 'wb') as f:

for chunk in r.iter_content(chunk_size=8192):

f.write(chunk)

print('Downloaded', filename)

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/download/'

# This is a subset of the main HydroRivers dataset of all

# rivers having `UPLAND_SKM` value greater than 100 sq. km.

hydrorivers_file = 'hydrorivers_100.gpkg'

hydrorivers_url = data_url + 'hydrosheds/'

countries_file = 'ne_10m_admin_0_countries_ind.zip'

countries_url = data_url + 'naturalearth/'

download(hydrorivers_url + hydrorivers_file)

download(countries_url + countries_file)Data Pre-Processing

Read the countries shapefile.

For the assignment, you need to pick the country for which you want

to create the map. We can print a list of values from the

SOVEREIGNT column of country_gdf GeoDataFrame

using country_gdf.SOVEREIGNT.values to know the names of

all countries.

Select a country name. Replace the value below with your chosen country.

Apply filters to select the country feature. We use an additional

filter TYPE != 'Dependency' to exclude overseas

territories. You may have to adjust the filter to get the correct

country polygon.

selected_country = country_gdf[

(country_gdf['SOVEREIGNT'] == country) &

(country_gdf['TYPE'] != 'Dependency')

]

selected_countryWe read the river network data from HydroRivers. We specify the

mask parameter which clips the layer to the country

boundary while reading the data.

This step can take a few minutes depending on the size of the country.

hydrorivers_filepath = os.path.join(data_folder, hydrorivers_file)

river_gdf = gpd.read_file(hydrorivers_filepath, mask=selected_country)

river_gdfVisualize the river network.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 10))

title = f'Rivers of {country}'

river_gdf.plot(ax=ax)

ax.set_title(title)

ax.set_axis_off()

plt.show()We want to style the rivers so that the width of the line is

proportional to the value in the UPLAND_SKM attribute. We

add a new column width to the GeoDataFrame by scaling the

input values to a range of target widths.

Tip: These values will play an important role in your final visualization. Adjust these to suit the range of values for your country.

original_min = 300

original_max = 10000

target_min = 0.2

target_max = 0.9

scaled = (river_gdf['UPLAND_SKM'] - original_min) / (original_max - original_min)

river_gdf['width'] = scaled.clip(0, 1) * (target_max - target_min) + target_min

river_gdf_final = river_gdf.sort_values(['UPLAND_SKM', 'width'])[

['MAIN_RIV', 'UPLAND_SKM', 'width', 'geometry']]

river_gdf_finalYour task is to take the river_gdf_final GeoDataFrame

and render the river network by applying the following styling

guidelines. Refer to the geopandas.GeoDataFrame.plot()

documentation for parameter values and options.

- Assign a color to each river segment based on the value of

MAIN_RIVcolumn. Hint: setcategorical=True. - Assign width to each item based on the value in the

widthcolumn. - Set the map background to black.

- Set the title to white and change the font to be larger.

Interactive Maps with Folium

Overview

Folium is a Python library that allows you to create interactive maps based on the popular Leaflet javascript library.

In this section, we will learn how to create an interactive map showing driving directions between two locations.

Setup

Folium Basics

We will learn the basics of folium by creating an interactive map showing the driving directions between two chosen locations. Let’s start by defining the coordinates of two cities.

To create a map, we initialize the folium.Map() class

which creates a map object with the default basemap. To display the map

a Jupyter notebook, we can simply enter the name of the map object.

The default map spans the full width of the Jupyter notebook - making

it difficult to navigate. The Map() constructor supports

width and height parameters that control the

size of the leaflet map, but you still end up with a lot of extra empty

space below the map. The preferred way to get a map of exact size is to

create a Figure first and add the map object to it.

from folium import Figure

fig = Figure(width=800, height=400)

m = folium.Map(location=[39.83, -98.58], zoom_start=4, width=800, height=400)

fig.add_child(m)The map object m can be manipulated by adding different

elements to it. Contrary to how Matplotlib objects work, the map object

does not get emptied when displayed. So you are able to visualize and

incrementally add elements to it. Let’s add some markers to the map

using folium.map.Marker

class.

folium.Marker(san_francisco, popup='San Francisco').add_to(m)

folium.Marker(new_york, popup='New York').add_to(m)

mThe markers can be customized to have a different color or icons. You

can check the folium.map.Icon

class for options for creating icons. This class supports a vast range

of icons from the fontawesome

icons and bootstrap icons

libraries. You can choose the name of the icon from there to use it in

your Folium map. The prefix parameter can be fa

for FontAwesome icons or glyphicon for Bootstrap3.

from folium import Figure

fig = Figure(width=800, height=400)

m = folium.Map(location=[39.83, -98.58], zoom_start=4)

folium.Marker(

san_francisco,

popup='San Francisco',

icon=folium.Icon(

color='green', icon='crosshairs', prefix='fa')

).add_to(m)

folium.Marker(

new_york,

popup='New York',

icon=folium.Icon(

color='red', icon='crosshairs', prefix='fa')

).add_to(m)

fig.add_child(m)We will be using OpenRouteService API to calculate the directions. Visit HeiGIT Sign Up page and create an account. Once your account is activated, visit your Dashboard. Copy the long string for Basic Key key and enter it below.

import requests

san_francisco = (37.7749, -122.4194)

new_york = (40.661, -73.944)

parameters = {

'api_key': ORS_API_KEY,

'start' : '{},{}'.format(san_francisco[1], san_francisco[0]),

'end' : '{},{}'.format(new_york[1], new_york[0])

}

response = requests.get(

'https://api.openrouteservice.org/v2/directions/driving-car', params=parameters)

if response.status_code == 200:

print('Request successful.')

data = response.text

else:

print('Request failed.')The API response is formatted as a GeoJSON string.

We can parse the GeoJSON as a dictionary and extract the route summary returned by the API which contains the total driving distance in meters.

parsed_data = json.loads(data)

summary = parsed_data['features'][0]['properties']['summary']

distance = round(summary['distance']/1000)

tooltip = 'Driving Distance: {} km'.format(distance)

tooltipWe can use the folium.features.GeoJson

class to load any data in the GeoJSON format directly. We can specify a

smooth_factor parameter which can be used to simplify the

line displayed when zoomed-out. Setting a higher number results in

better performance.

Folium maps can be saved to a HTML file by calling

save() on the map object.

Exercise

- Create an interactive map of driving directions between two of your chosen cities.

- Cutomize the marker icons to a car icon. Reference

folium.map.Icon. - Change the route line to red color with a line width of 1

pixels. Reference

folium.features.GeoJSONStyling

Use the code block below as the starting point and replace the variables below with those of your chosen locations and insert your own API key.

import folium

from folium import Figure

import json

import requests

###############################

### Replace Variables Below

###############################

origin = (37.7749, -122.4194)

origin_name = 'San Francisco'

destination = (40.661, -73.944)

destination_name = 'New York'

map_center = (39.83, -98.58)

ORS_API_KEY = ''

###############################

parameters = {

'api_key': ORS_API_KEY,

'start' : '{},{}'.format(origin[1], origin[0]),

'end' : '{},{}'.format(destination[1], destination[0])

}

response = requests.get(

'https://api.openrouteservice.org/v2/directions/driving-car', params=parameters)

if response.status_code == 200:

print('Request successful.')

data = response.text

else:

print('Request failed.')

parsed_data = json.loads(data)

summary = parsed_data['features'][0]['properties']['summary']

distance = round(summary['distance']/1000)

tooltip = 'Driving Distance: {} km'.format(distance)

fig = Figure(width=800, height=400)

m = folium.Map(location=map_center, zoom_start=4)

folium.Marker(

origin,

popup=origin_name,

icon=folium.Icon(

color='green', icon='car', prefix='fa')

).add_to(m)

folium.Marker(

destination,

popup=destination_name,

icon=folium.Icon(

color='red', icon='car', prefix='fa')

).add_to(m)

folium.GeoJson(

data,

tooltip=tooltip,

smooth_factor=1,

).add_to(m)

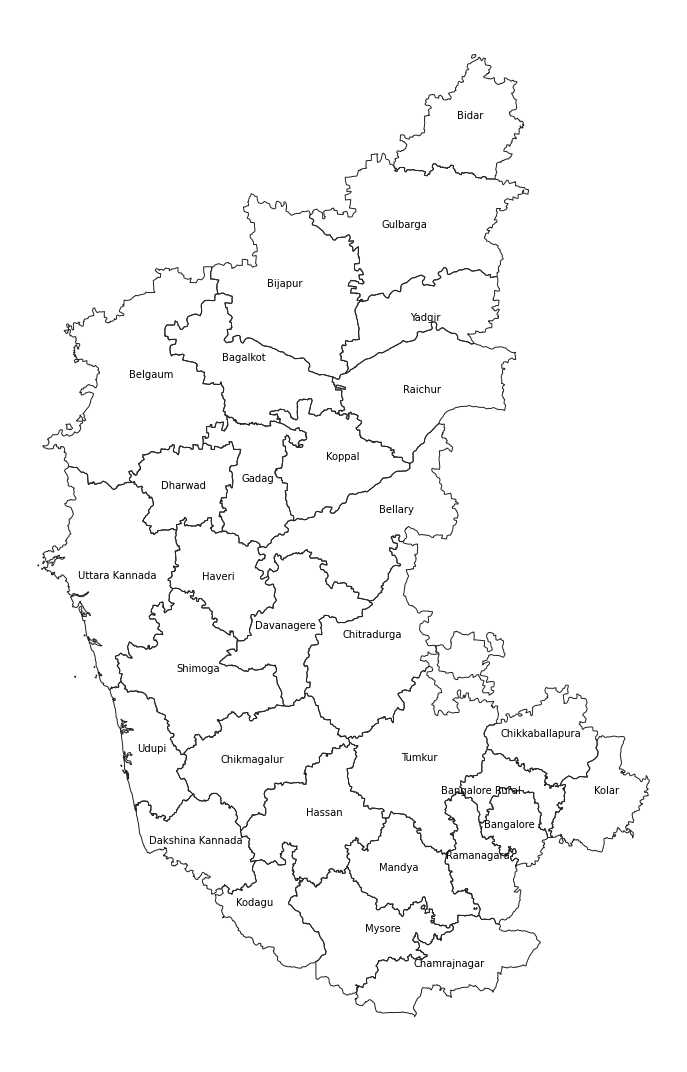

fig.add_child(m)Multi-layer Interactive Maps

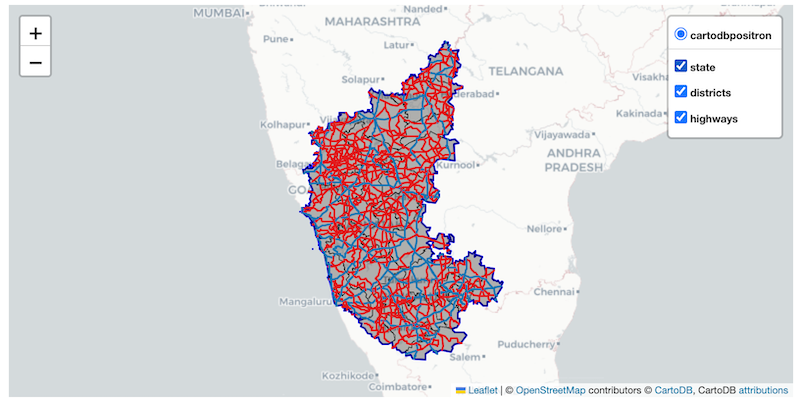

Open the notebook named 09_multilayer_maps.ipynb.

Overview

Folium

supports creating maps with multiple layers. Recent versions of

GeoPandas have built-in support to create interactive folium maps from a

GeoDataFrame using the explore() function.

In this section, we will create a multi-layer interactive map using 2 vector datasets.

Setup and Data Download

import os

import fiona

import folium

from folium import Figure

import geopandas as gpd

import requestsdata_folder = 'data'

output_folder = 'output'

if not os.path.exists(data_folder):

os.mkdir(data_folder)

if not os.path.exists(output_folder):

os.mkdir(output_folder)Using GeoPandas explore()

Read the individual layers from the GeoPackage using GeoPandas. First

we use fiona to list all available layers in the

GeoPackage.

data_pkg_path = 'data'

filename = 'karnataka.gpkg'

path = os.path.join(data_pkg_path, filename)

layers = fiona.listlayers(path)

layersroads_gdf = gpd.read_file(path, layer='karnataka_highways')

districts_gdf = gpd.read_file(path, layer='karnataka_districts')

state_gdf = gpd.read_file(path, layer='karnataka')We can use the explore()

method to create an interactive folium map from the GeoDataFrame. When

you call explore() a folium object is created. You can save

that object and use it to display or add more layers to the map.

The default output of the explore() method is a

full-width folium map. If you need more control, a better approach is to

create a follium.Figure object and add the map to it. For

this approach we need to first compute the extent of the map.

Now we can create a figure of the required size, and add a folium map

to it. The explore() function takes a m

agrument where we can supply an existing folium map to which to render

the GeoDataFrame.

fig = Figure(width=800, height=400)

m = folium.Map()

m.fit_bounds([[bounds[1],bounds[0]], [bounds[3],bounds[2]]])

districts_gdf.explore(m=m)

fig.add_child(m)Folium supports a variety of basemaps. Let’s change the basemap to

use Cartodb Positron tiles. Additionally, we can change the

styling using the color and style_kwds

parameters.

Reference: Folium Tiles

fig = Figure(width=800, height=400)

m = folium.Map(tiles='Cartodb Positron')

m.fit_bounds([[bounds[1],bounds[0]], [bounds[3],bounds[2]]])

districts_gdf.explore(

m=m,

color='black',

style_kwds={'fillOpacity': 0.3, 'weight': 0.5},

)

fig.add_child(m)Let’s add the roads_gdf layer to the map.

The GeoDataFrame contains roads of different categories as given in

the ref column. Let’s add a category column so we can use

it to apply different styles to each category of the road.

def get_category(row):

ref = str(row['ref'])

if 'NH' in ref:

return 'NH'

elif 'SH' in ref:

return 'SH'

else:

return 'NA'

roads_gdf['category'] = roads_gdf.apply(get_category, axis=1)

roads_gdfNow we can use the category column to style the layer

with different colors. Additionally, we customize the

tooltip to show only the selected columns when hovering

over a feature and tooltip_kwds to customize the name of

the column being displayed.

fig = Figure(width=800, height=400)

m = folium.Map(tiles='Cartodb Positron')

m.fit_bounds([[bounds[1],bounds[0]], [bounds[3],bounds[2]]])

roads_gdf.explore(

m=m,

column='category',

categories=['NH', 'SH'],

cmap=['#1f78b4', '#e31a1c'],

categorical=True,

tooltip=['ref'],

tooltip_kwds={'aliases': ['name']}

)

fig.add_child(m)Create Multi-layer Maps

When you call explore() a folium object is created. You

can save that object and add more layers to the same object.

fig = Figure(width=800, height=400)

m = folium.Map(tiles='Cartodb Positron')

m.fit_bounds([[bounds[1],bounds[0]], [bounds[3],bounds[2]]])

districts_gdf.explore(

m=m,

color='black',

style_kwds={'fillOpacity': 0.3, 'weight':0.5},

name='districts',

tooltip=False)

roads_gdf.explore(

m=m,

column='category',

categories=['NH', 'SH'],

cmap=['#1f78b4', '#e31a1c'],

categorical=True,

tooltip=['ref'],

tooltip_kwds={'aliases': ['name']},

name='highways'

)

fig.add_child(m)To make our map easier to explore, we also add a Layer

Control that displays the list of layers on the top-right corner

and also allows the users to turn them on or off. The name

parameter to the explore() function controls the name that

will be displayed in the layer control.

Exercise

Add the state_gdf layer to the folium map below with a

thick blue border and no fill. Save the resulting map as a HTML file on

your computer.

Hint: Use the style_kwds with ‘fill’ and

‘weight’ options.

Use the code below as your starting point for the exercise.

fig = Figure(width=800, height=400)

m = folium.Map(tiles='Cartodb Positron')

m.fit_bounds([[bounds[1],bounds[0]], [bounds[3],bounds[2]]])

districts_gdf.explore(

m=m,

color='black',

style_kwds={'fillOpacity': 0.3, 'weight':0.5},

name='districts',

tooltip=False)

roads_gdf.explore(

m=m,

column='category',

categories=['NH', 'SH'],

cmap=['#1f78b4', '#e31a1c'],

categorical=True,

tooltip=['ref'],

name='highways',

tooltip_kwds={'aliases': ['name']}

)

fig.add_child(m)

folium.LayerControl().add_to(m)

mLeafmap Basics

Overview

Leafmap is a Python package for interactive mapping that supports a wide-variety of plotting backends.

We will explore the capabilities of Leafmap and create a map that includes vector and raster layers. For a more comprehensive overview, check out leafmap key Features.

Setup and Data Download

data_folder = 'data'

output_folder = 'output'

if not os.path.exists(data_folder):

os.mkdir(data_folder)

if not os.path.exists(output_folder):

os.mkdir(output_folder)Creating a Map

You can change the basemap to a Google basemap and set the center of

the map. leafmap.Map() supports many arguments to customize

the map and available controls.

References:

Adding Data Layers

Leafmap’s foliumap module supports adding a variety of

data types along with helper functions such as

set_center(). Let’s add a GeoJSON file to the map using

add_geojson().

Reference: leafmap.foliumap.Map.add_geojson

m = leafmap.Map(width=800, height=500)

json_filepath = os.path.join(data_folder, json_file)

m.add_geojson(json_filepath, layer_name='City')

m.set_center(77.59, 12.97, 10)

mWe can also add any vector layer that can be read by GeoPandas. Here

we add a line layer from a GeoPackage using the add_gdf()

function. The styling parameters can be any folium supported styles.

m = leafmap.Map(width=800, height=500)

gpkg_filepath = os.path.join(data_folder, gpkg_file)

roads_gdf = gpd.read_file(gpkg_filepath)

m.add_gdf(roads_gdf, layer_name='Roads', style={'color':'blue', 'weight':0.5})

m.zoom_to_gdf(roads_gdf)

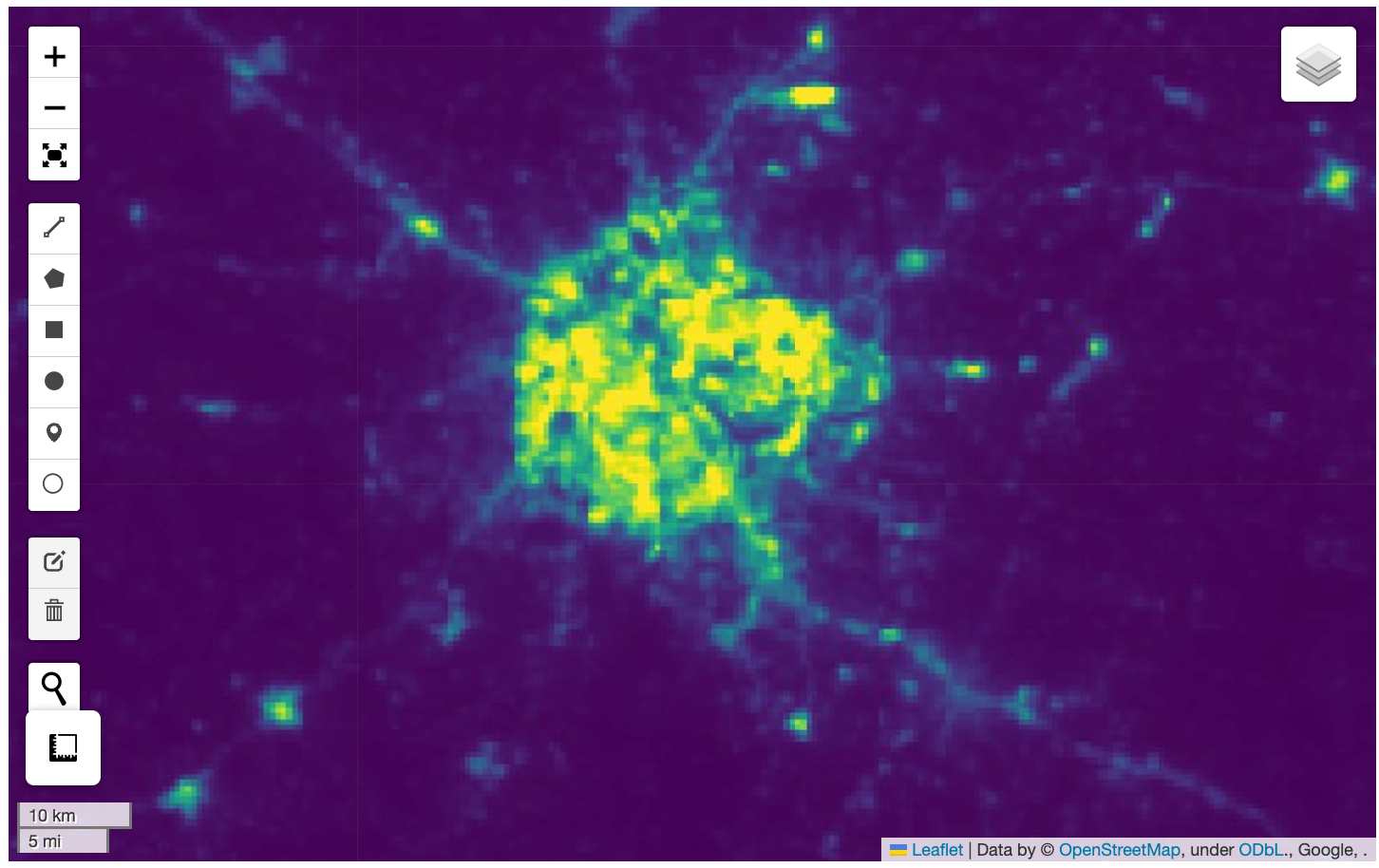

mA very useful feature of LeafMap is the ability to load a

Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF (COG) file directly from a URL without the need

of a server. The file is streamed directly and high-resolution tiles are

automatically fetched as you zoom in. We load a 8-bit RGB image hosted

on GitHub using the add_cog_layer() function.

Reference: leafmap.Map.add_cog_layer

m = leafmap.Map(width=800, height=500)

bounds = leafmap.cog_bounds(cog_url)

m.add_cog_layer(cog_url, name='Land Use Land Cover')

m.zoom_to_bounds(bounds)

mLeafmap also supports adding custom legends. We define a list of

color codes and labels for the land cover classes contained in the

bangalore_lulc.tif image. We can now add a legend to the

map using the add_legend() function.

Reference: leafmap.foliumap.Map.add_legend

m = leafmap.Map(width=800, height=500)

bounds = leafmap.cog_bounds(cog_url)

m.add_cog_layer(cog_url, name='Land Use Land Cover')

m.zoom_to_bounds(bounds)

# Add a Legend

colors = ['#006400', '#ffbb22','#ffff4c','#f096ff','#fa0000',

'#b4b4b4','#f0f0f0','#0064c8','#0096a0','#00cf75','#fae6a0']

labels = ["Trees","Shrubland","Grassland","Cropland","Built-up",

"Barren / sparse vegetation","Snow and ice","Open water",

"Herbaceous wetland","Mangroves","Moss and lichen"]

m.add_legend(colors=colors, labels=labels)

mWe can save the resulting map to a HTML file using the

to_html() function.

m = leafmap.Map(width=800, height=500)

bounds = leafmap.cog_bounds(cog_url)

m.add_cog_layer(cog_url, name='Land Use Land Cover')

m.zoom_to_bounds(bounds)

# Add a Legend

colors = ['#006400', '#ffbb22','#ffff4c','#f096ff','#fa0000',

'#b4b4b4','#f0f0f0','#0064c8','#0096a0','#00cf75','#fae6a0']

labels = ["Trees","Shrubland","Grassland","Cropland","Built-up",

"Barren / sparse vegetation","Snow and ice","Open water",

"Herbaceous wetland","Mangroves","Moss and lichen"]

m.add_legend(colors=colors, labels=labels)

output_file = 'lulc.html'

output_path = os.path.join(output_folder, output_file)

m.to_html(output_path)Exercise

We want to visualize a large (7.9GB) raster on the map. The URL to a Cloud Optmized GeoTiff (COG) file hosted on Google Cloud Storage is given below. Add the raster to the map, apply a colormap and zoom the map to your region of interest.

Use the code block below as your starting point.

Hints:

- The GeoTIFF image is a single-band image with grayscale values of

night time light intensities. Specify additional

kwargsparameters fromleafmap.Map.add_cog_layer().- The range of these values are between 0-60. Use

rescale='0,60'. - A grayscale image can be displayed in color using a named colormap.

For example

colormap_name='viridis'. - The map automatically zooms to the extent of the COG. Turn that

behavior off by supplying

zoom_to_layer=False.

- The range of these values are between 0-60. Use

- To zoom to your chosen region, use

leafmap.Map.zoom_to_bounds()method with the bounding box in the[minx, miny, maxx, maxy]format. You can use this bounding box app to find the coordinates for your region.

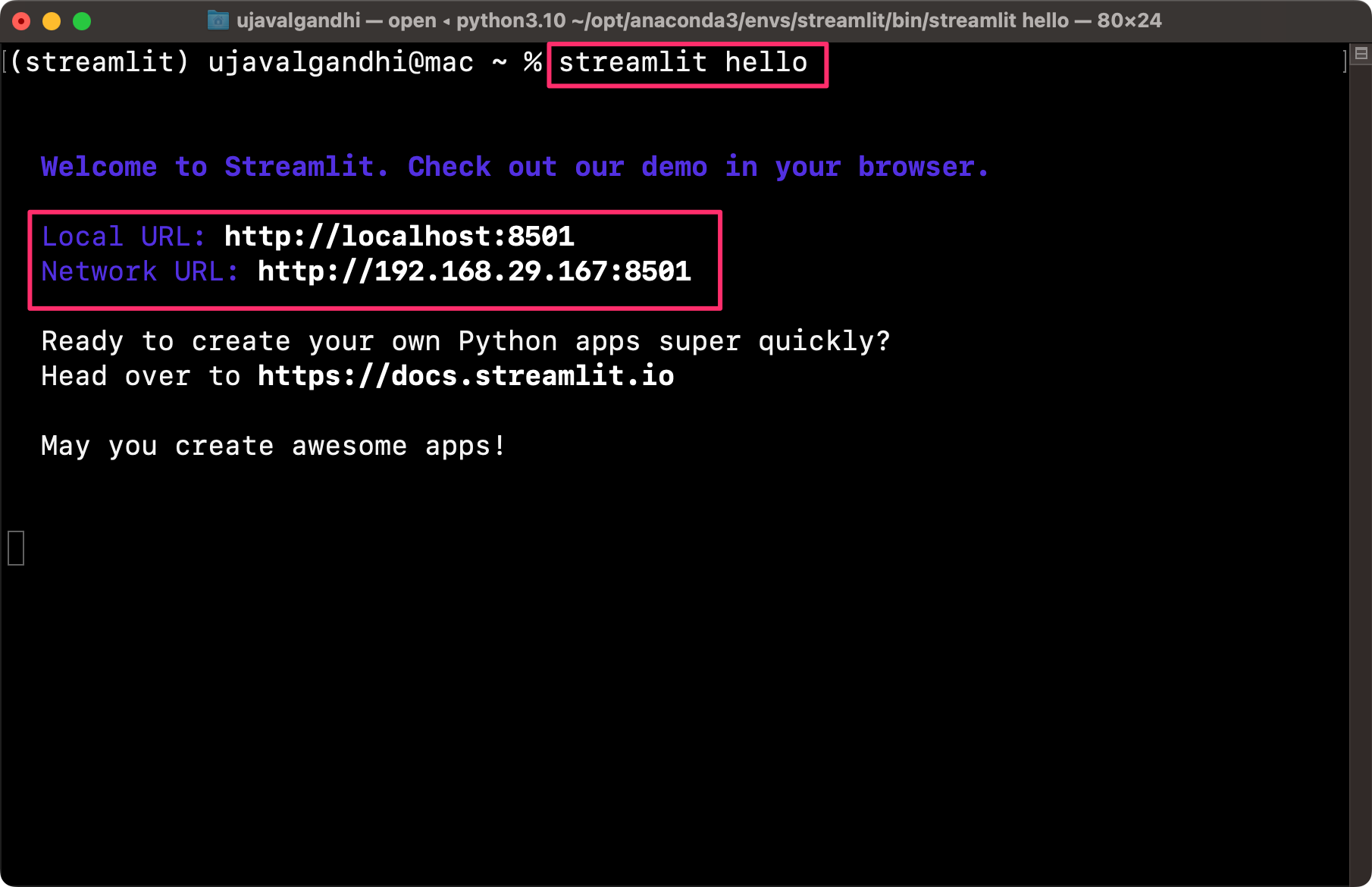

Streamlit Basics

Streamlit is a Python library that allows you to create web-apps and

dashboard by just writing Python code. It provides you with a wide range

of UI widgets and layouts that can be used to build user- interfaces.

Your streamlit app is just a regular Python file with a .py

extension.

Installation and Setting up the Environment

You need to install the streamlit package to create the

app. We will be using Anaconda to install streamlit and

related packages on your machine. Please review the Anaconda

Installation Guide for step-by-step instructions.

- Once you have installed Anaconda, open Anaconda Prompt or a Terminal and run the following commands.

conda update --all

conda create --name streamlit -y

conda activate streamlit- Now your environment is ready. We will install the required

packages. First install

geopandas.

conda install -c conda-forge geopandas -y- Next we will install

streamlitandleafmap.

conda install -c conda-forge streamlit streamlit-folium leafmap -yIf the conda install completes successfully, move to Step 4.

Some users have reported problems where conda is not able to resolve

the environment for installing these packages. Here is an alternate

installation procedure if you face difficulties with above. After

installing geopandas, switch to using pip for installing

the remaining packages.

pip install streamlit streamlit-folium leafmap- After the installation is done, run the following command.

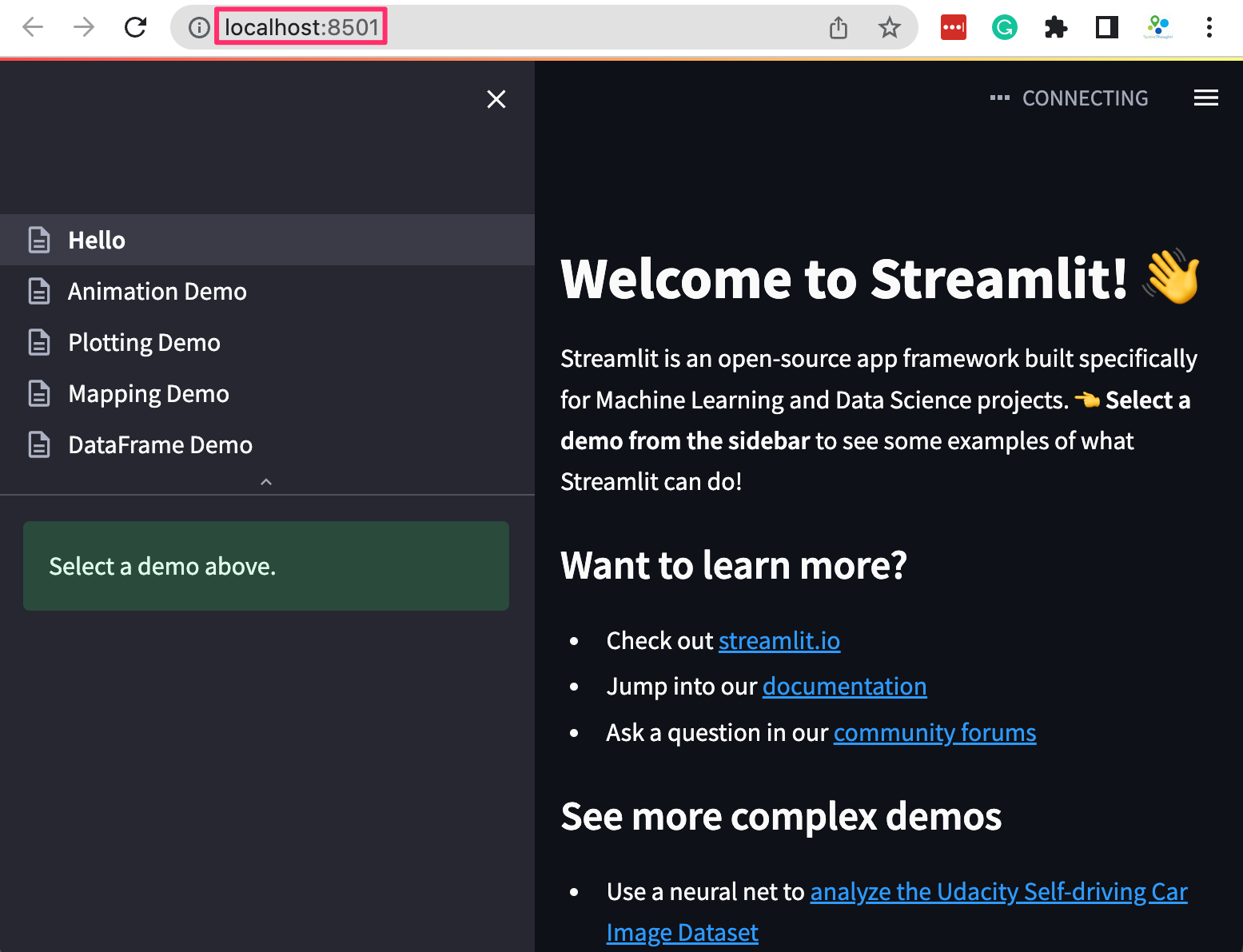

streamlit hello

A new browser tab will open and display the streamlit Hello app.

Your installation is now complete. You can close the terminal window to stop the streamlit server.

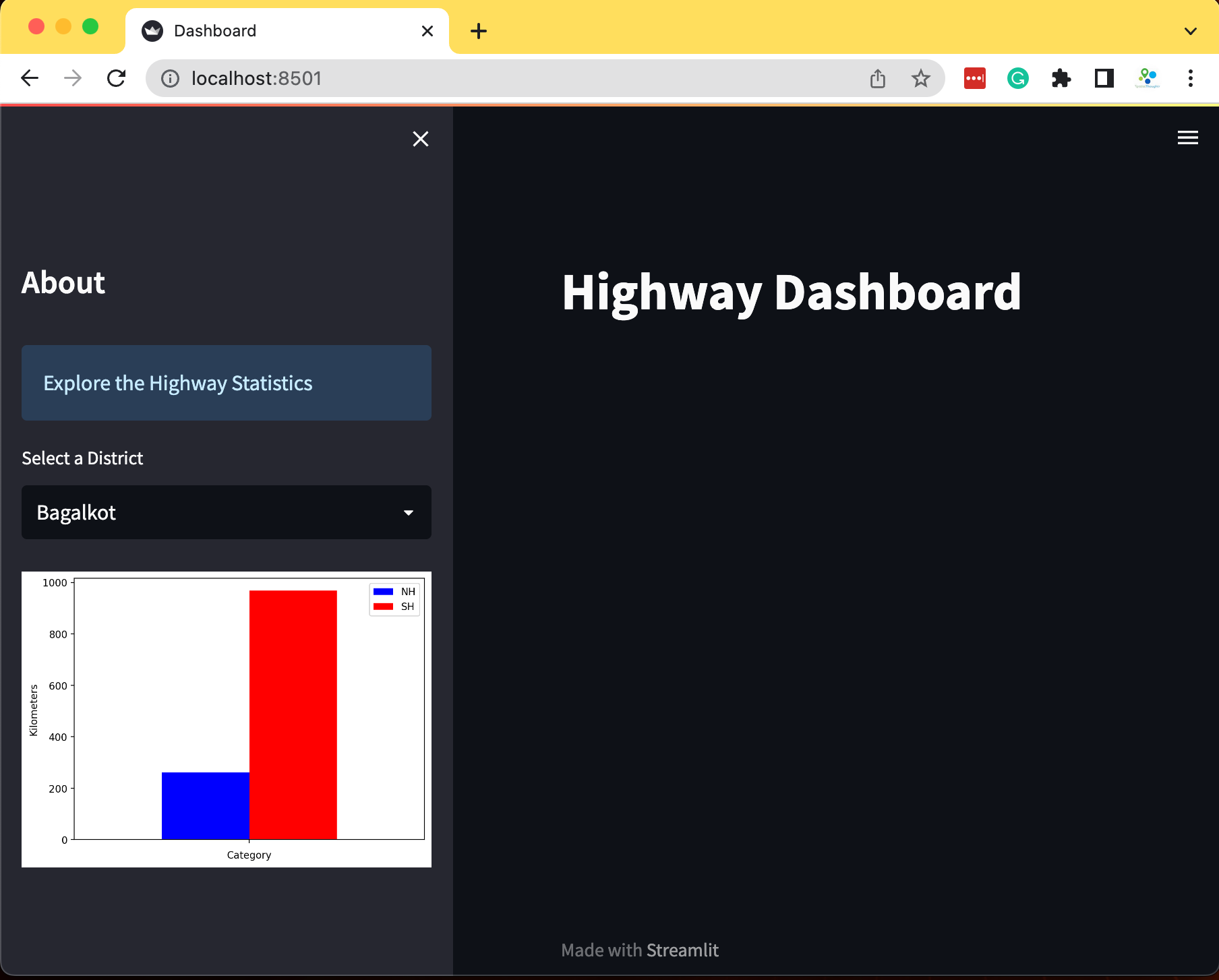

Create a Simple Dashboard

Let’s create a simple interactive dashboard by loading a CSV file and displaying a chart with some statistics. We will get familiar with the streamlit app development workflow and explore different widgets and layout elements.

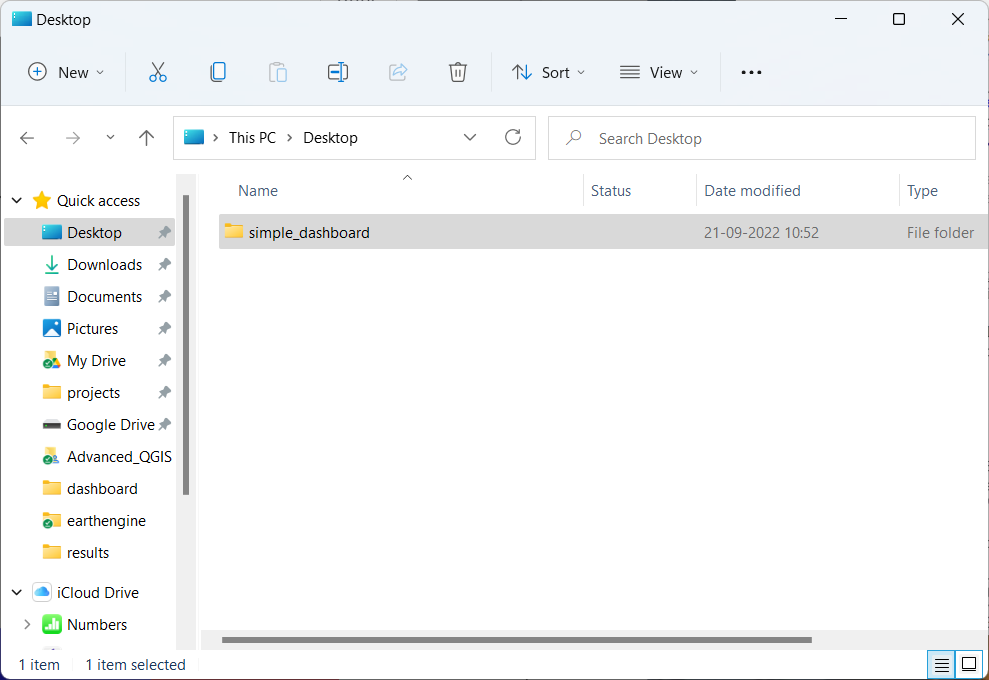

- Create a folder named simple_dashboard on your Desktop.

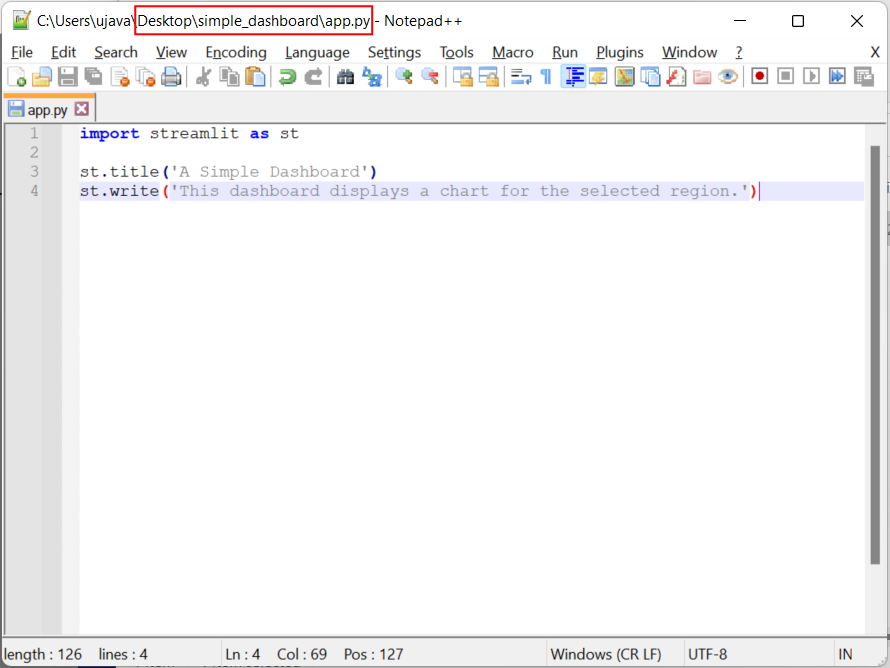

- Open your favorite text editor and create a file with the following

content. By convention, we import

streamlit as st. Then we can use thest.title()to display the title of our dashboard andst.write()to add a paragraph of text. Save the file in the simple_dashboard folder on your desktop asapp.py

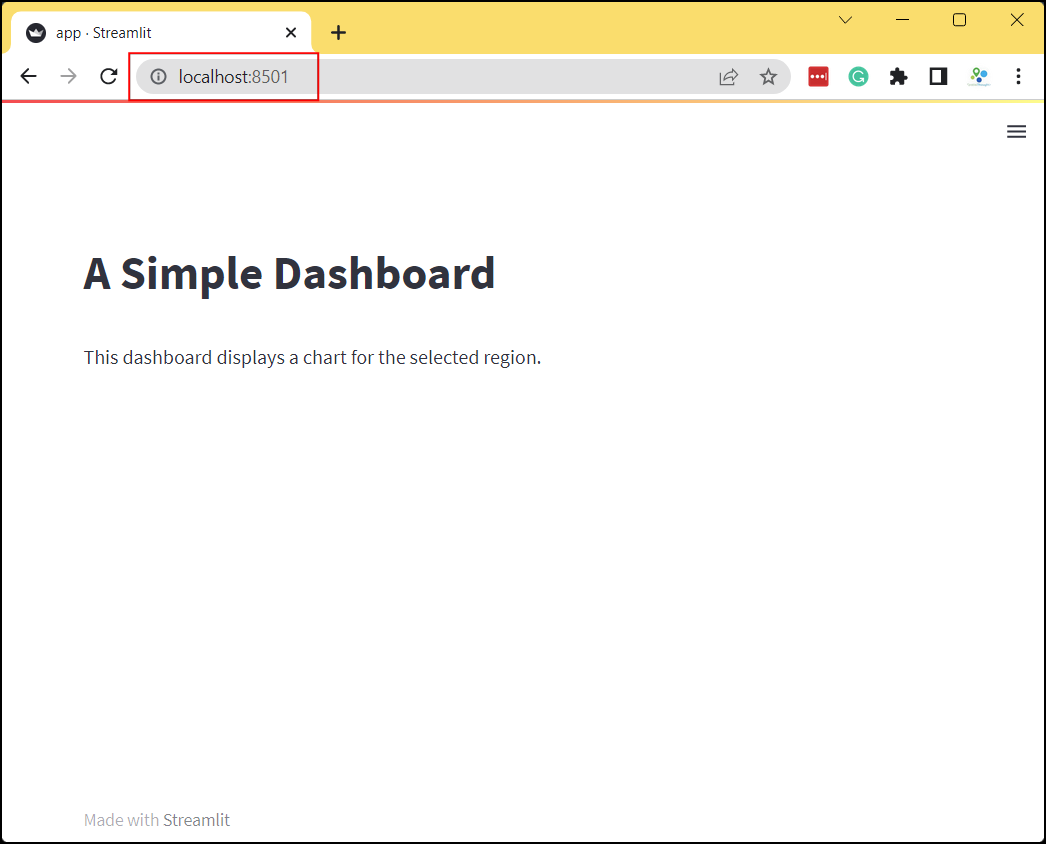

import streamlit as st

st.title('A Simple Dashboard')

st.write('This dashboard displays a chart for the selected region.')

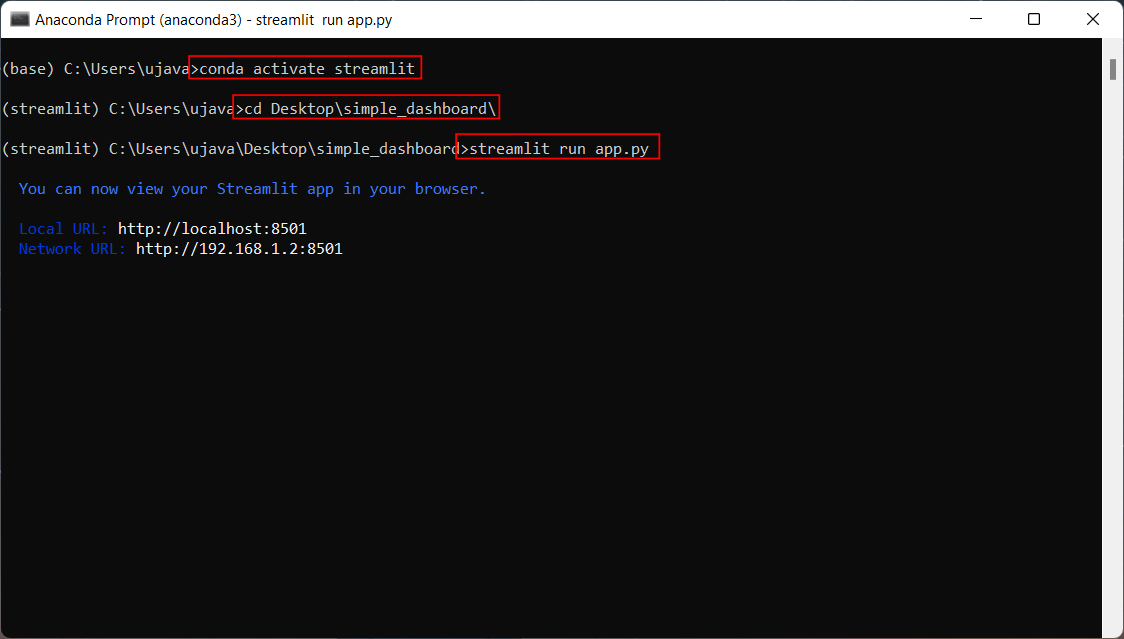

- Once the file is saved, open Anaconda Prompt (Windows) or

Terminal (Mac/Linux). Switch to the conda environment where you

have installed the required packages. We then use

cdcommand to change the current directory to the once with theapp.pyfile. Then run the following command to start the streamlit server and launch the app.

- A new browser tab will open and display the output of the app.

- Let’s read some data and display it. We load a CSV file from a URL

using Pandas and get a DataFrame object. We then use

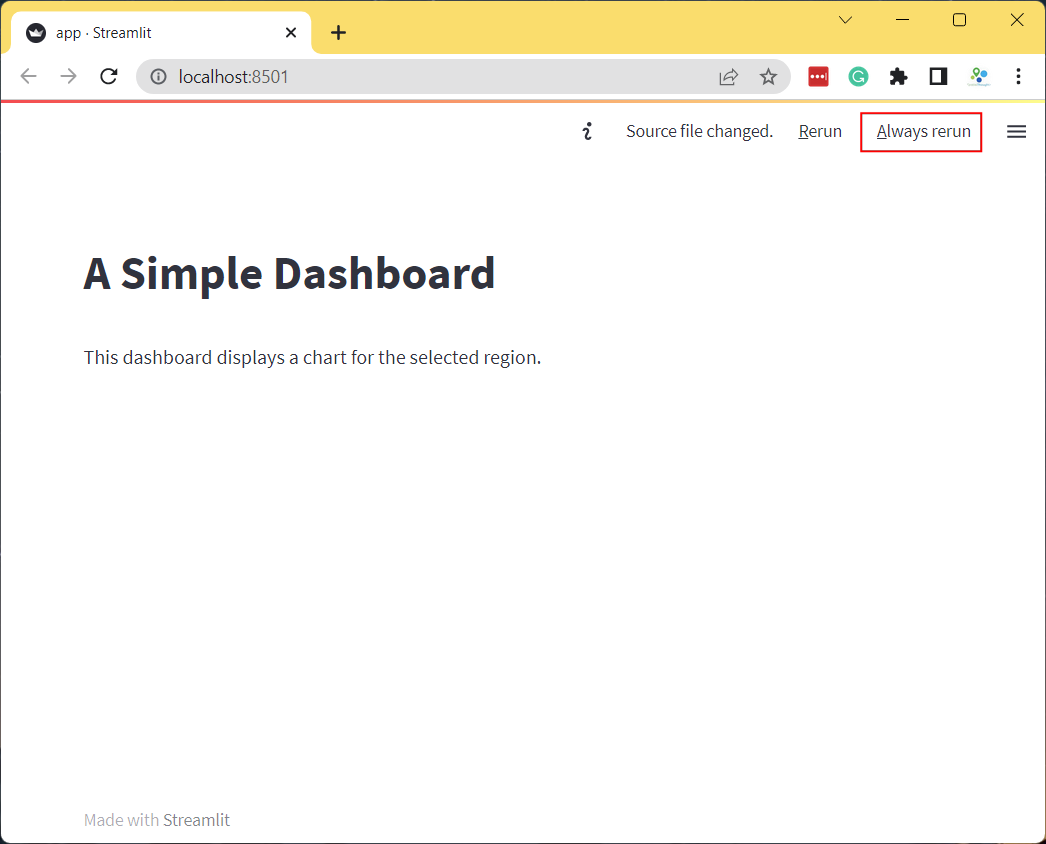

st.dataframe()widget to render the dataframe. Update yourapp.pywith the following code. As you save the file, you will notice that streamlit will detect it and display a prompt to re-run your app. Choose Always rerun.

import streamlit as st

import pandas as pd

st.title('A Simple Dashboard')

st.write('This dashboard displays a chart for the selected region.')

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/' \

'download/osm/'

csv_file = 'highway_lengths_by_district.csv'

url = data_url + csv_file

df = pd.read_csv(url)

st.dataframe(df)

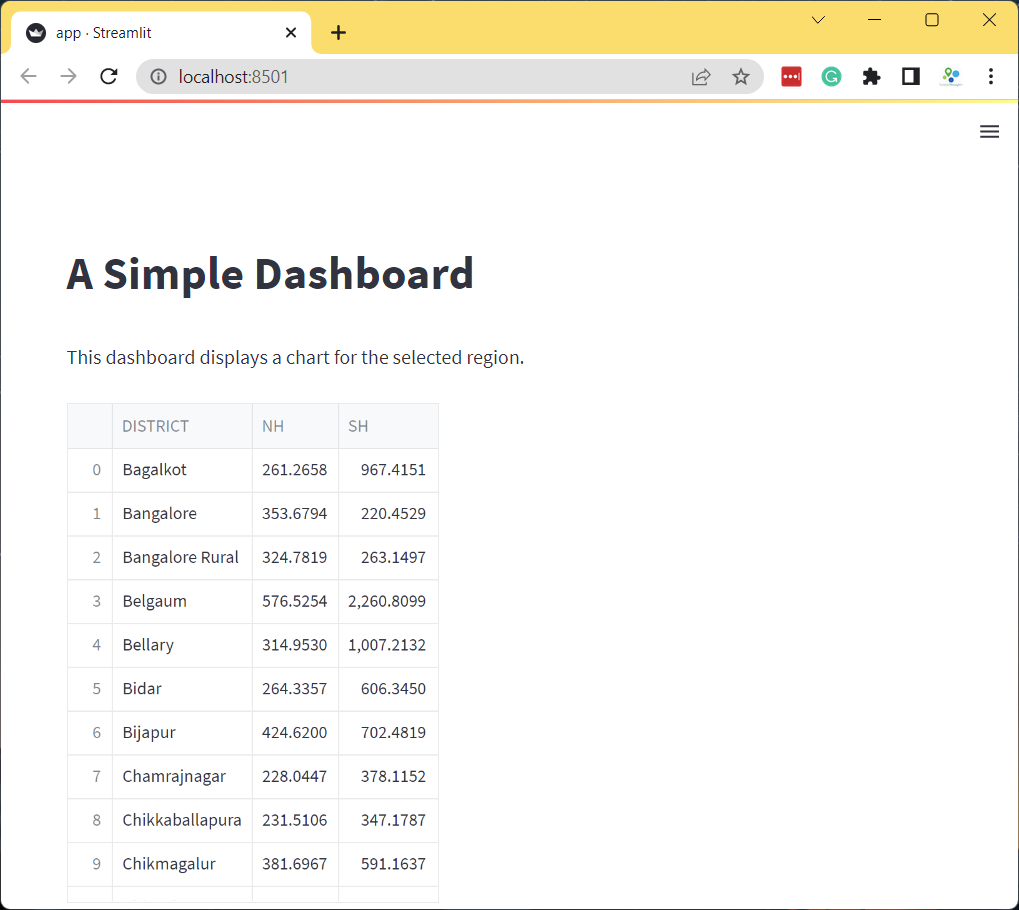

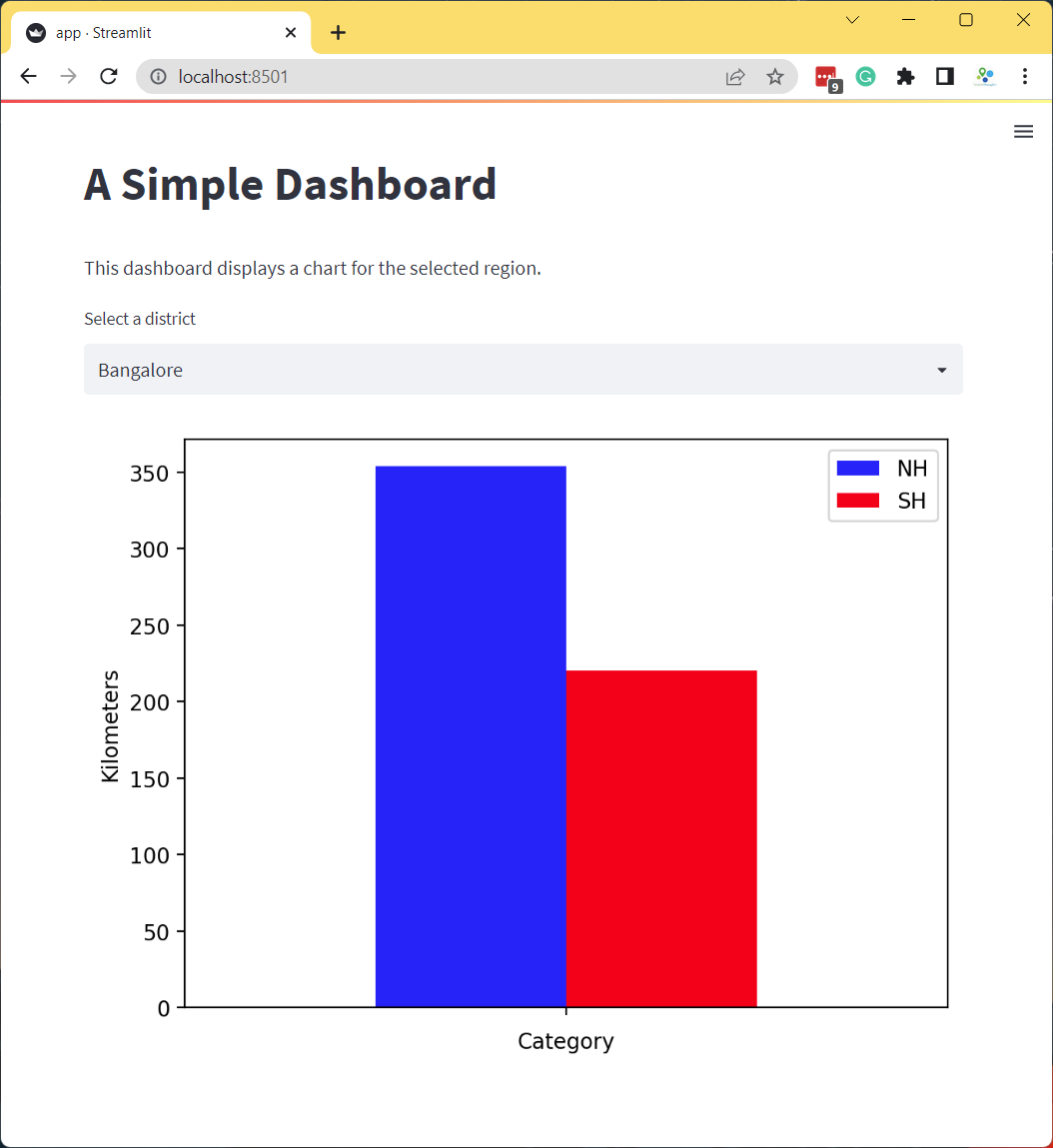

- The app will now display the dataframe. The dataframe consists of 3

columns. The

DISTRICTcolumn contains a unique name for the admin region. The NH and SH columns contain the length of National Highways and State Highways in Kilometers for each admin region. We will now create a dashboard that displays a chart with the lengths of highways for the user-selected admin region.

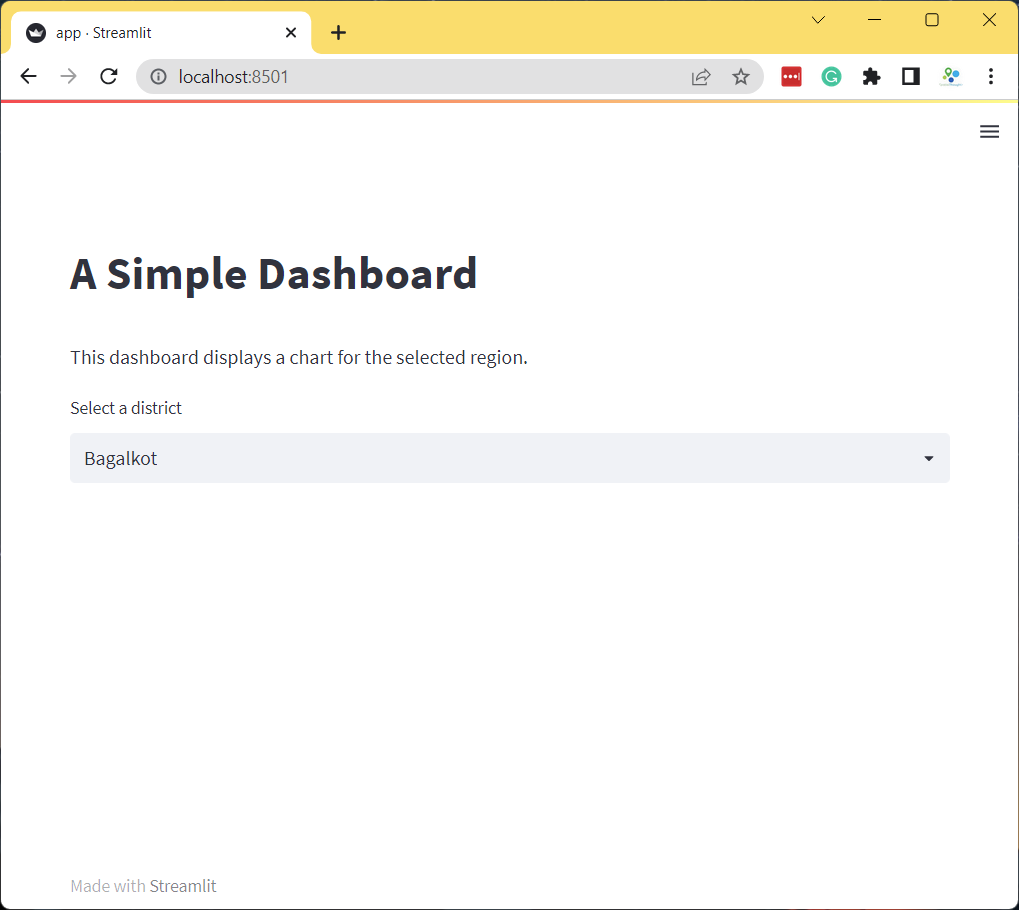

- Let’s add a dropdown menu with the list of admin regions. We first

get the names from the

DISTRICTcolumn and usest.selectbox()to add a dropdown selector. Streamlit apps always run the entireapp.pywhenever any selection is changed. With our current app structure, whenever the user selected a new admin region, the source file will be fetched again and a new dataframe will be created. This is not required as the source data does not change on every interaction. A good practice is to put the data fetching in a function and use the@st.cache_datadecorator which will cache the results. Anytime the function is called with the same arguments, it will return the cached version of the data instead of fetching it.

import streamlit as st

import pandas as pd

st.title('A Simple Dashboard')

st.write('This dashboard displays a chart for the selected region.')

@st.cache_data

def load_data():

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/' \

'download/osm/'

csv_file = 'highway_lengths_by_district.csv'

url = data_url + csv_file

df = pd.read_csv(url)

return df

df = load_data()

districts = df.DISTRICT.values

district = st.selectbox('Select a district', districts)

- As the user selects an admin region from the selectbox, the selected

value is saved in the

districtvariable. We use it to filter the DataFrame to the selected district. Then we use Matplotlib to create a bar-chart with the filtered dataframe and display it usingst.pyplot()widget.

import streamlit as st

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

st.title('A Simple Dashboard')

st.write('This dashboard displays a chart for the selected region.')

@st.cache_data

def load_data():

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/' \

'download/osm/'

csv_file = 'highway_lengths_by_district.csv'

url = data_url + csv_file

df = pd.read_csv(url)

return df

df = load_data()

districts = df.DISTRICT.values

district = st.selectbox('Select a district', districts)

filtered = df[df['DISTRICT'] == district]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

filtered.plot(kind='bar', ax=ax, color=['#0000FF', '#FF0000'],

ylabel='Kilometers', xlabel='Category')

ax.set_xticklabels([])

stats = st.pyplot(fig)

- Our dashboard now displays an updated chart every-time you change

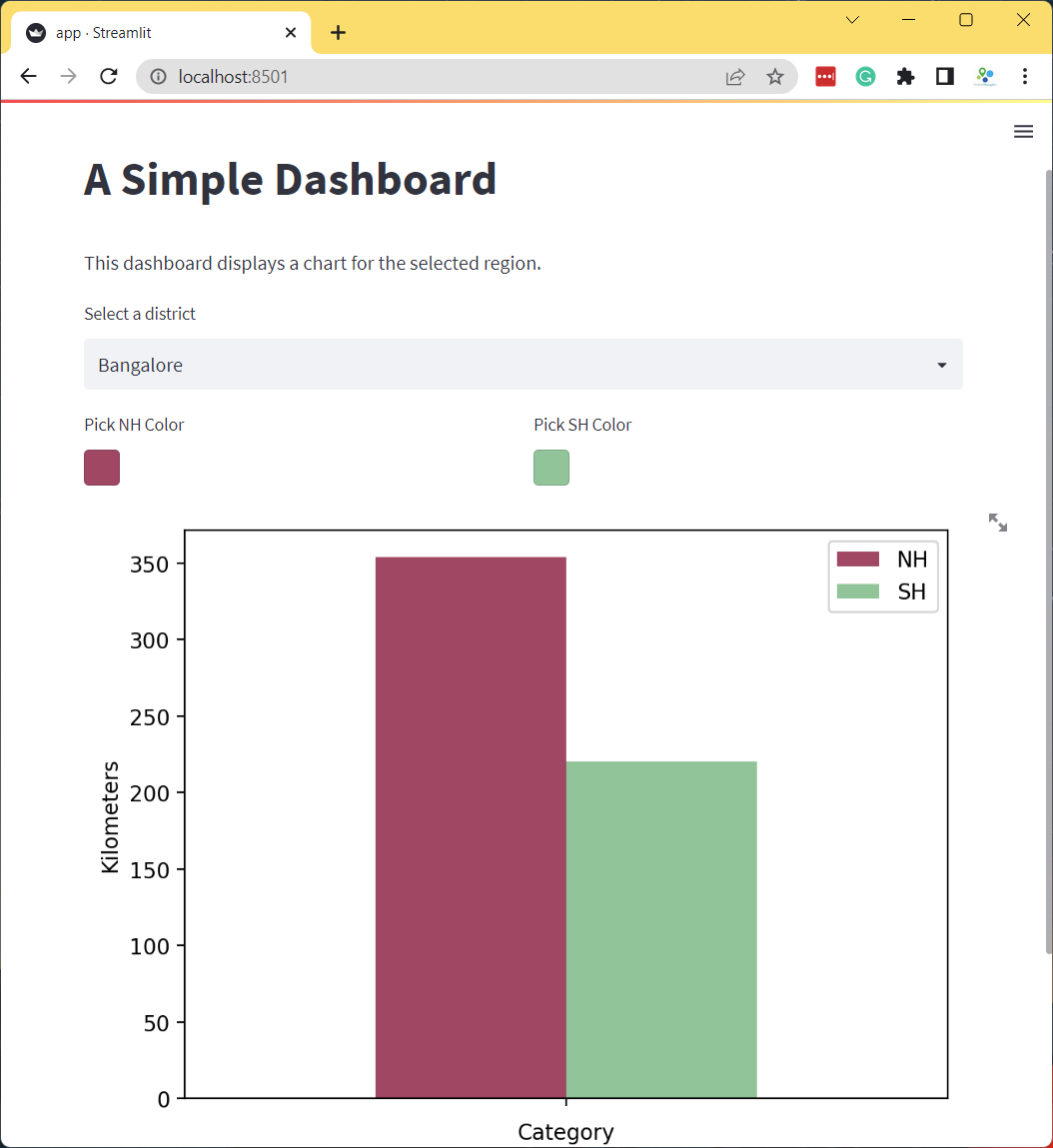

the selection. Streamlit provides many other user-interface widgets.

Let’s explore some more of them. We will use

st.color_picker()widget to allow users to customize the color of the bar chart. We can display 2 color-pickers side-by-side using a column layout. We usest.columns()to create 2 columnscol1andcol2. We add acolor_picker()to each column with appropriate label and a default color. If we have more than 1 widget of the same type in the app, we need to provide a uniquekeythat can be used to identify the widget. We make some final tweaks to the chart and complete the dashboard.

import streamlit as st

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

st.title('A Simple Dashboard')

st.write('This dashboard displays a chart for the selected region.')

@st.cache_data

def load_data():

data_url = 'https://github.com/spatialthoughts/python-dataviz-web/releases/' \

'download/osm/'

csv_file = 'highway_lengths_by_district.csv'

url = data_url + csv_file

df = pd.read_csv(url)

return df

df = load_data()

districts = df.DISTRICT.values

district = st.selectbox('Select a district', districts)

filtered = df[df['DISTRICT'] == district]

col1, col2 = st.columns(2)

nh_color = col1.color_picker('Pick NH Color', '#0000FF')

sh_color = col2.color_picker('Pick SH Color', '#FF0000')

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1)

filtered.plot(kind='bar', ax=ax, color=[nh_color, sh_color],

ylabel='Kilometers', xlabel='Category')

ax.set_title('Length of Highways')

ax.set_ylim(0, 2500)

ax.set_xticklabels([])

stats = st.pyplot(fig)

Exercise

Add a radio-button to the app that allows the user to select the units for length between Kilometers and Miles as shown below. As the user toggles the radio-button, you should apply the appropriate conversion from Kilometer to Miles and update the chart.

- Hint1: Change

st.columns()to have 3 columns and save the results into 3 separate objects.col1, col2, col3 = st.columns(3) - Hint2: You can convert the values from Kilometer to Miles using

filtered = filtered[['NH', 'SH']]*0.621371

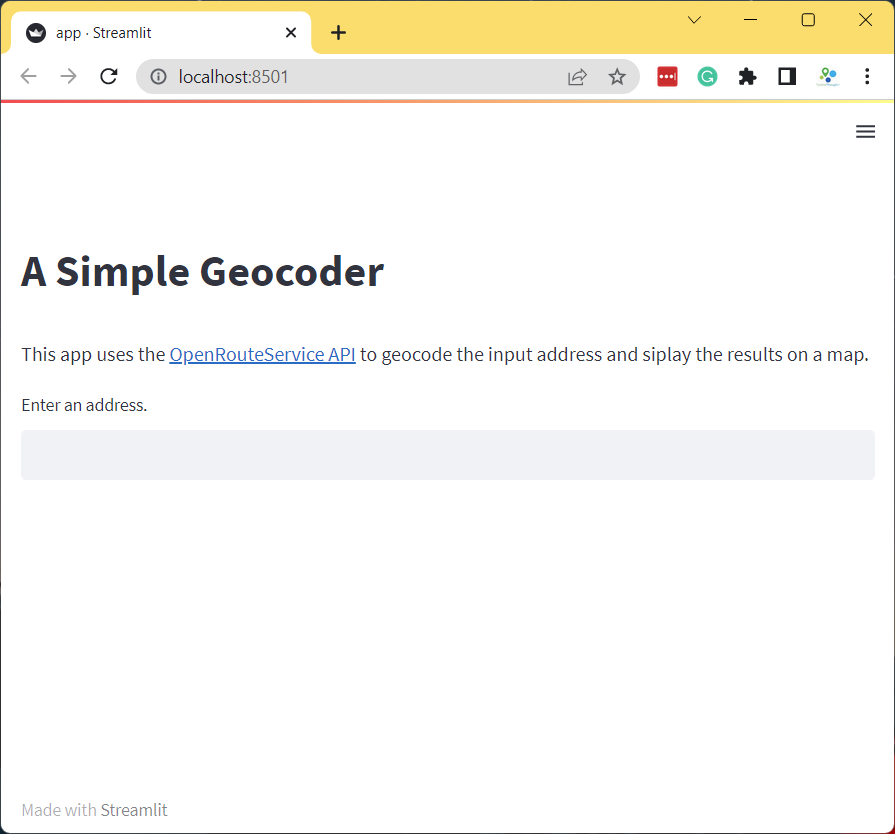

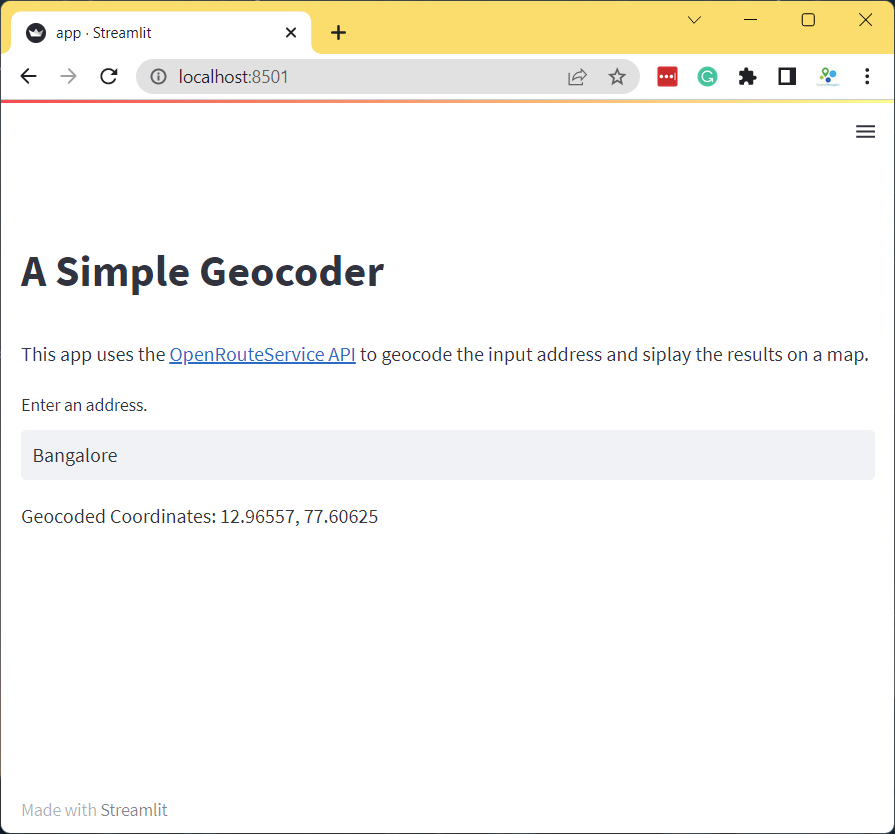

Create a Simple Geocoder App

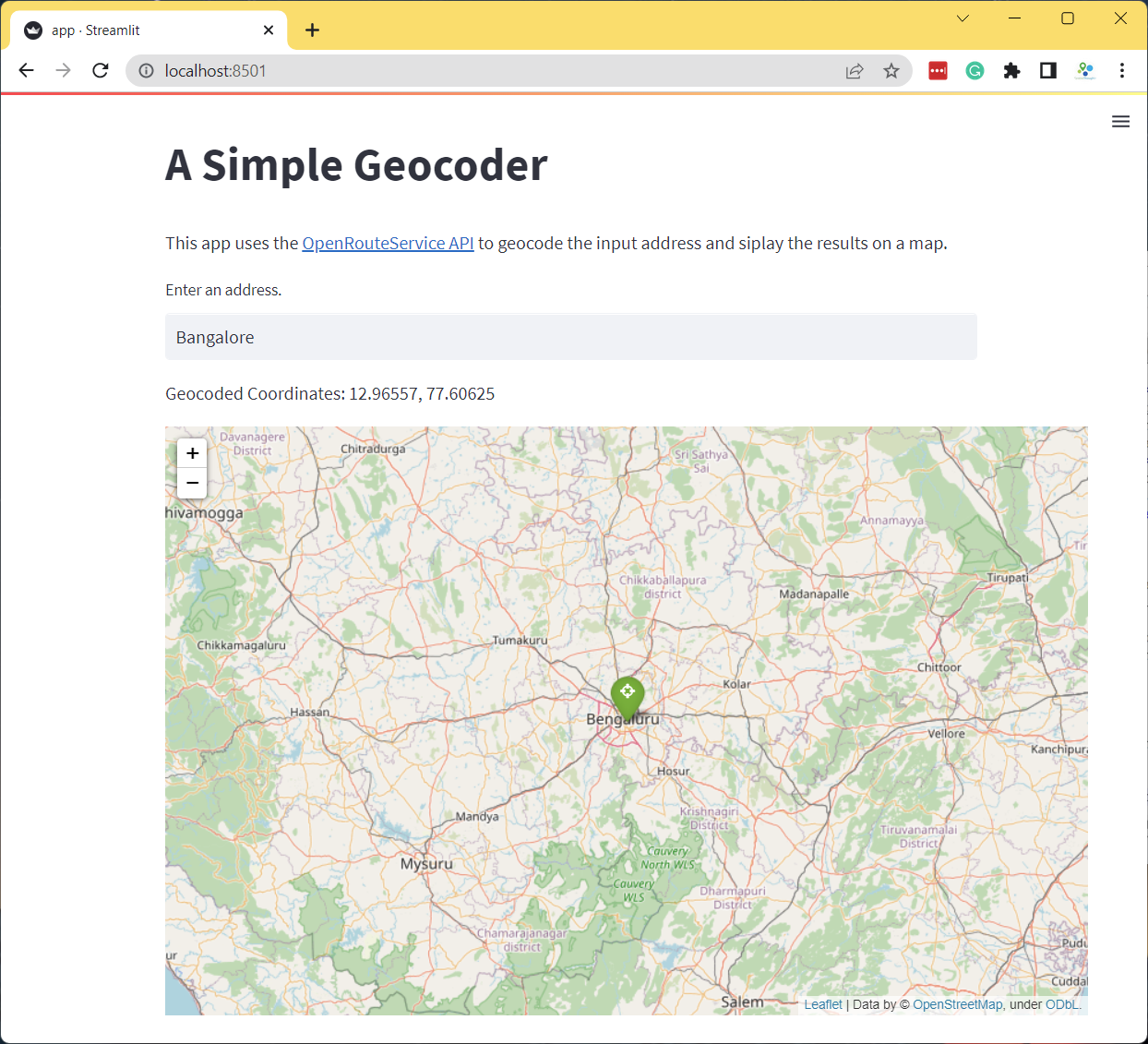

Let’s create a simple app that geocodes a user query and displays the results on a map. We will use OpenRouteService Geocoding API for geocoding and Folium to display the results on a map.

- We start by creating a new folder simple_app and

create the

app.pywith a basic layout with a title, a description and a text input for the address.

import folium

import requests

import streamlit as st

st.title('A Simple Geocoder')

st.markdown('This app uses the [OpenRouteService API](https://openrouteservice.org/) '

'to geocode the input address and display the results on a map.')

address = st.text_input('Enter an address.')

- Now we add a

geocode()function that will take an address and geocode it using OpenRouteService API.

import requests

import streamlit as st

st.title('A Simple Geocoder')

st.markdown('This app uses the [OpenRouteService API](https://openrouteservice.org/) '

'to geocode the input address and display the results on a map.')

address = st.text_input('Enter an address.')

ORS_API_KEY = '<your api key>'

@st.cache_data

def geocode(query):

parameters = {

'api_key': ORS_API_KEY,

'text' : query

}

response = requests.get(

'https://api.openrouteservice.org/geocode/search',

params=parameters)

if response.status_code == 200:

data = response.json()

if data['features']:

x, y = data['features'][0]['geometry']['coordinates']

return (y, x)

if address:

results = geocode(address)

if results:

st.write('Geocoded Coordinates: {}, {}'.format(results[0], results[1]))

else:

st.error('Request failed. No results.')

- Now that we have coordinates, we can display it on a map using the

st_foliumcomponent.

import folium

import requests

import streamlit as st

from streamlit_folium import st_folium

st.title('A Simple Geocoder')

st.markdown('This app uses the [OpenRouteService API](https://openrouteservice.org/) '

'to geocode the input address and siplay the results on a map.')

address = st.text_input('Enter an address.')

ORS_API_KEY = '<your api key>'

@st.cache_data

def geocode(query):

parameters = {

'api_key': ORS_API_KEY,

'text' : query

}

response = requests.get(

'https://api.openrouteservice.org/geocode/search',

params=parameters)

if response.status_code == 200:

data = response.json()

if data['features']:

x, y = data['features'][0]['geometry']['coordinates']

return (y, x)

if address:

results = geocode(address)

if results:

st.write('Geocoded Coordinates: {}, {}'.format(results[0], results[1]))

m = folium.Map(location=results, zoom_start=8)

folium.Marker(

results,

popup=address,

icon=folium.Icon(color='green', icon='crosshairs', prefix='fa')

).add_to(m)

# call to render Folium map in Streamlit, but don't get any data back

# from the map (so that it won't rerun the app when the user interacts)

st_folium(m, width=800, returned_objects=[])

else:

st.error('Request failed. No results.')

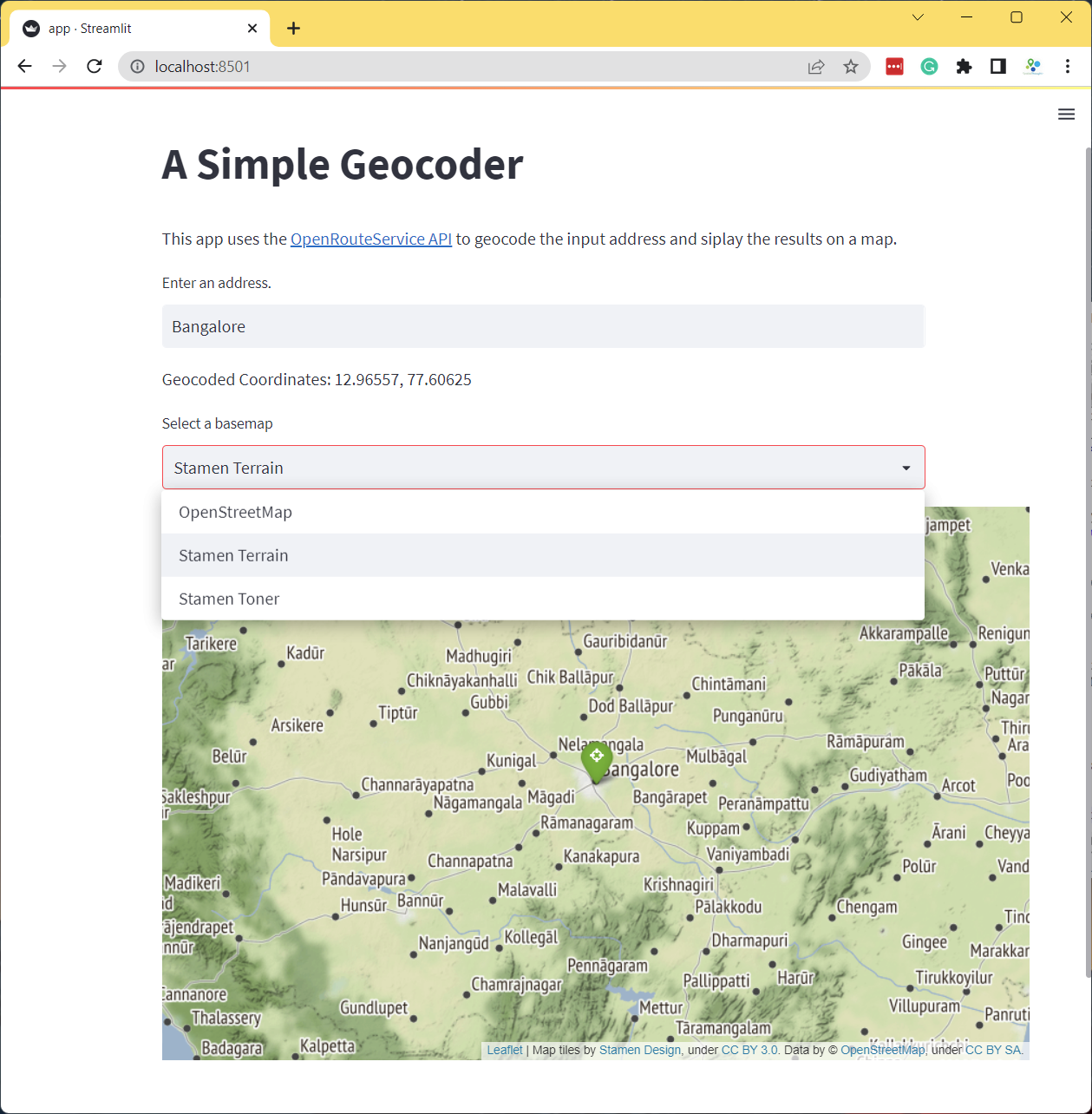

Exercise

Add a dropdown menu to give the users an option to change the default basemap of the Folium map.

- Hint: Add a

st.selectbox()with basemap strings.st.selectbox('Select a basemap', ['OpenStreetMap', 'CartoDB Positron', 'CartoDB DarkMatter'])

Reference: folium.folium.Map

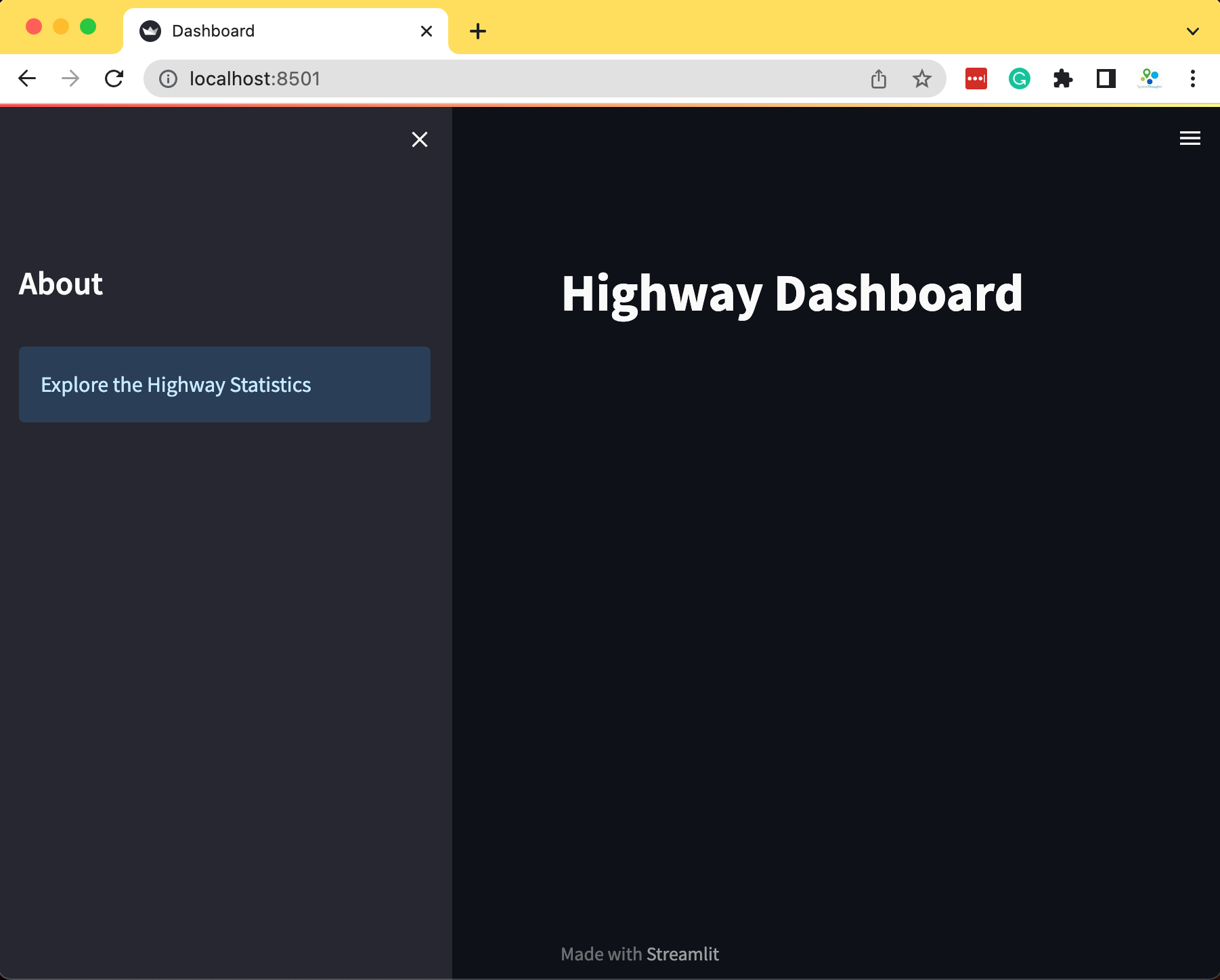

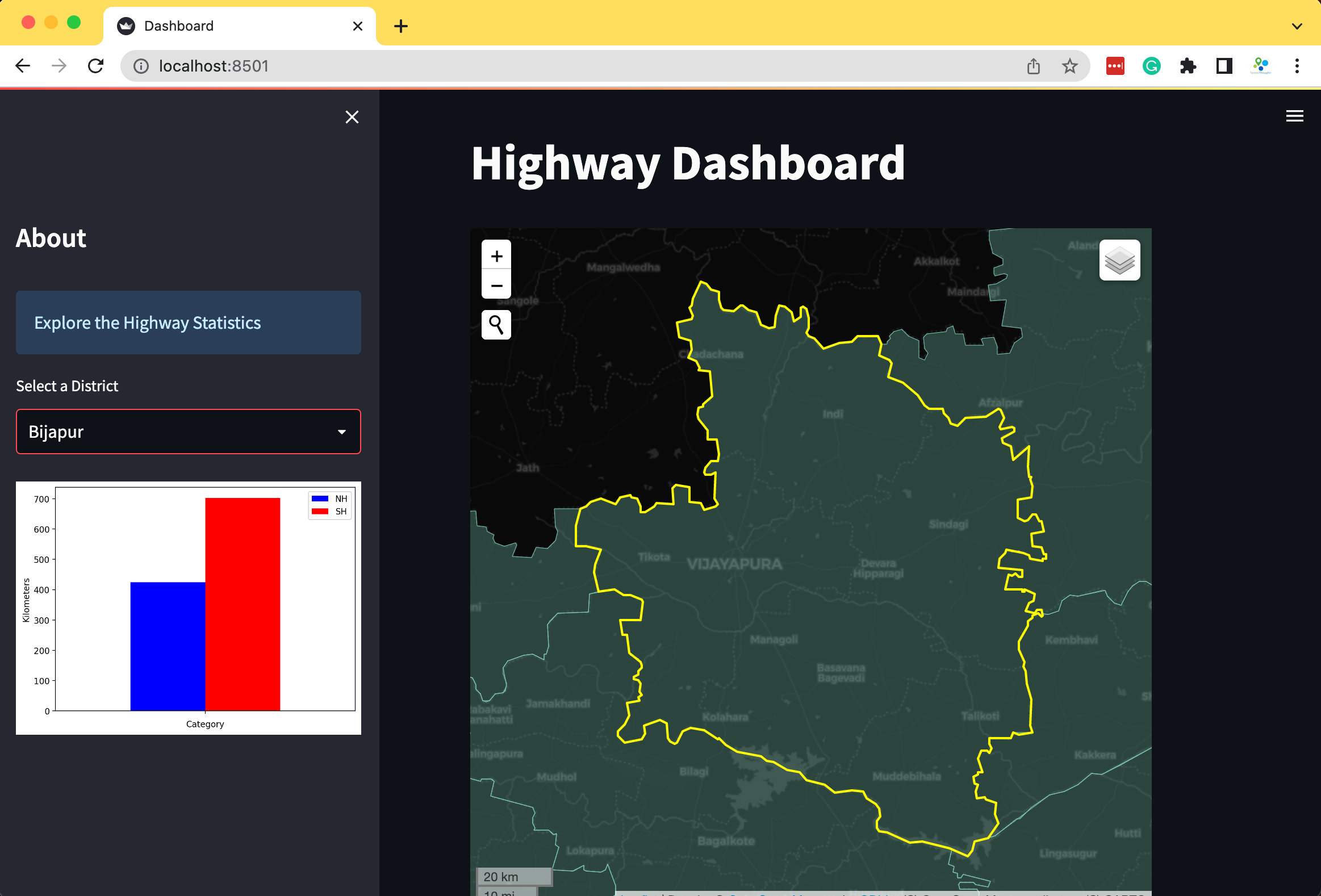

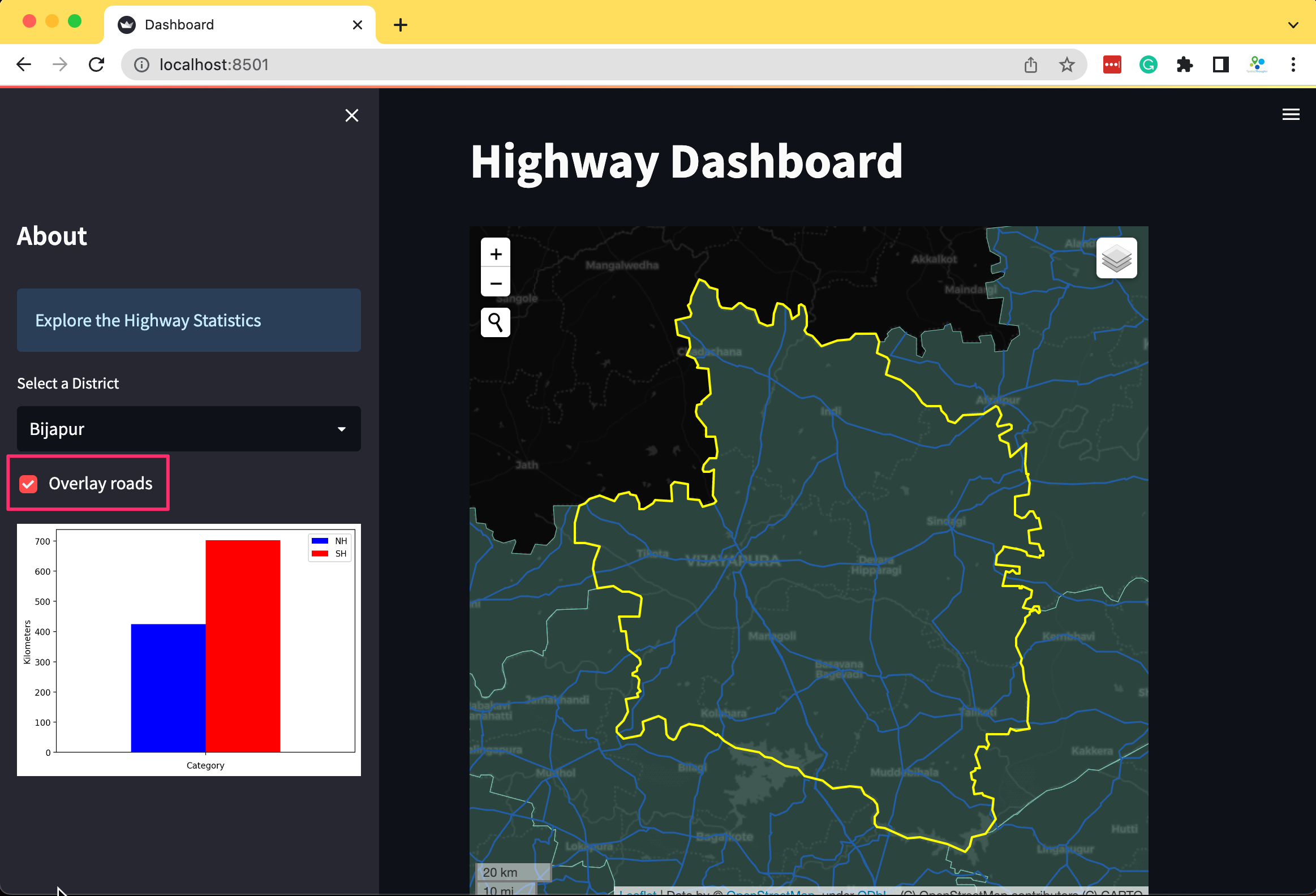

Building Mapping Apps with Leafmap and Streamlit

We can leverag leafmap to create an interactive mapping

dashboard that gives us the flexibility of using many different mapping

backends and way to read a wide-variety of spatial data formats.

Create a Mapping Dashboard

The code below creates an interactive mapping dashboard that displays the statistics of the selected region.

- We start by creating the app directory

mapping_dashboard and creating

app.pywith the following content. This code creates a layout with a sidebar usingst.sidebar()and adds some widgets to it. Note that while we need to usest.title()for the main section, we usest.sidebar.title()for the sidebar.

import streamlit as st

st.set_page_config(page_title='Dashboard', layout='wide')

st.title('Highway Dashboard')

st.sidebar.title('About')

st.sidebar.info('Explore the Highway Statistics')

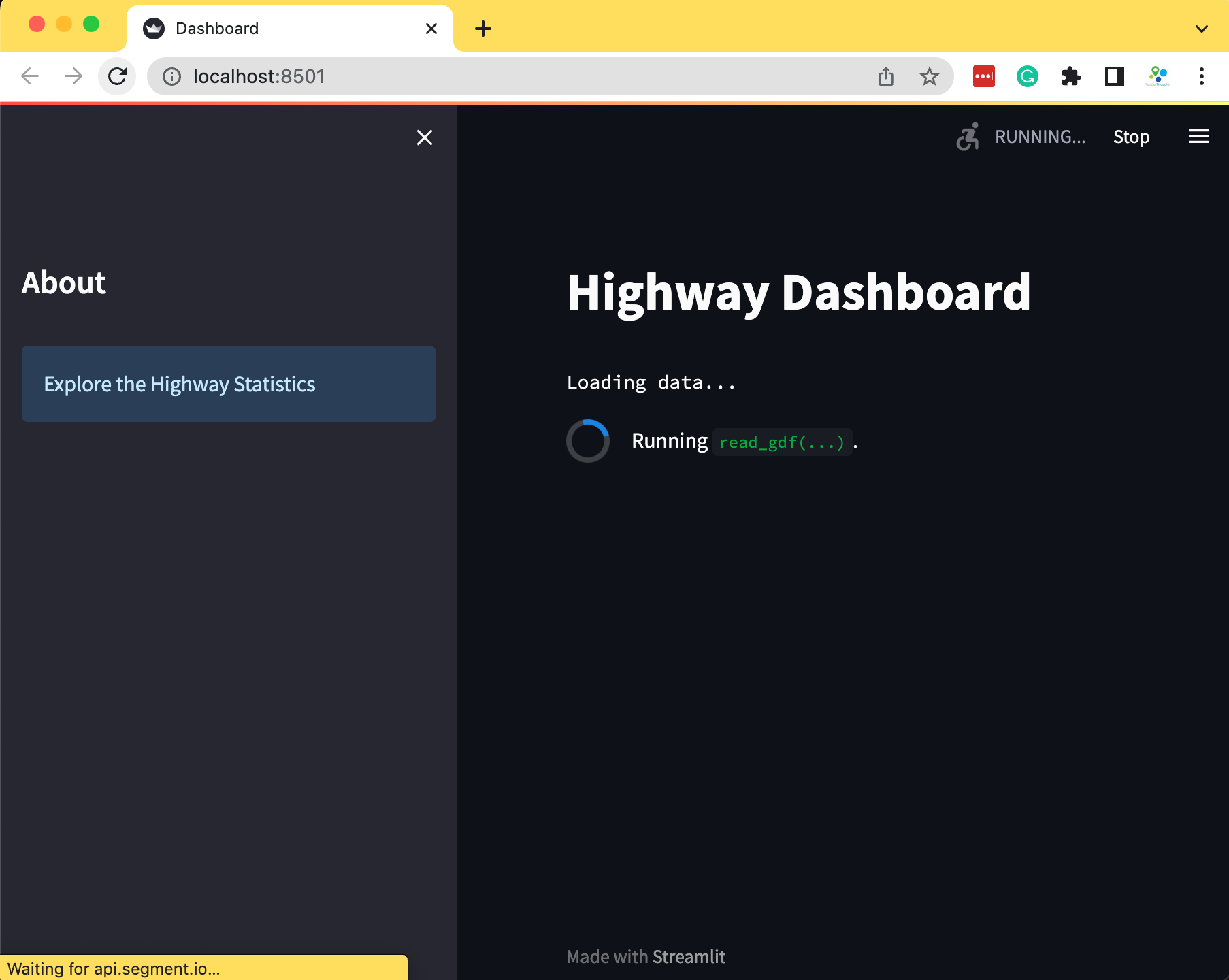

- We now use

geopandasto read 2 vector layers from a geopackage andpandasto read a CSV file containing road statistics. We put the code for data fetching inside a function and cache it using thest.cache_datadecorator.

import streamlit as st

import geopandas as gpd

import pandas as pd

st.set_page_config(page_title='Dashboard', layout='wide')

st.title('Highway Dashboard')

st.sidebar.title('About')

st.sidebar.info('Explore the Highway Statistics')